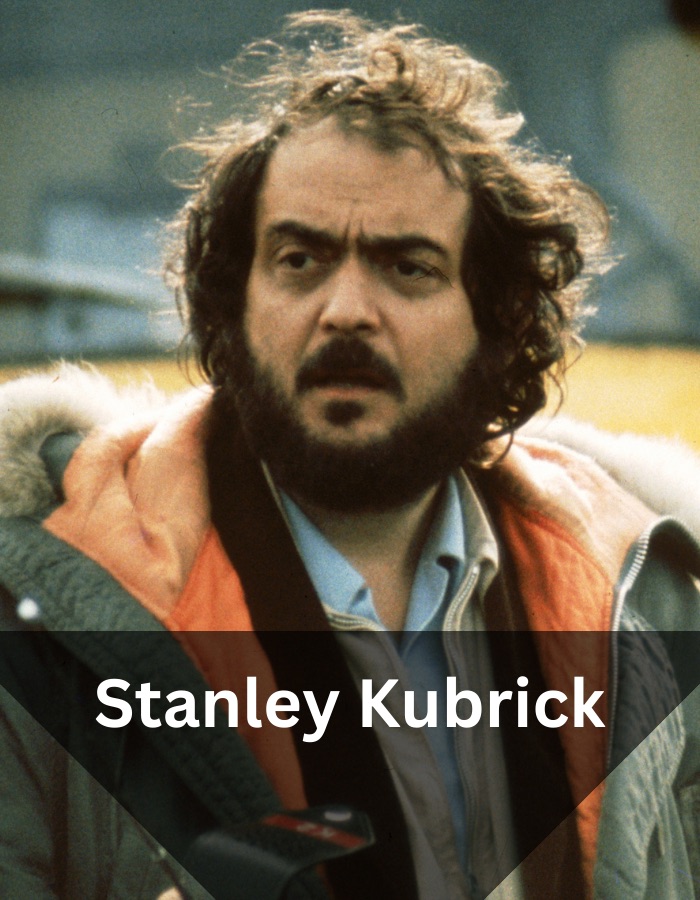

This 1920s generation came of age in the Second World War, and that distinctly impacted this group, who would go on to redefine cinema. Among these were individuals like Federico Fellini, Satyajit Ray, and Stanley Kubrick, each of whom brought a unique vision and style to the screen. Fellini’s work is often characterised by its dreamlike quality and extravagant imagery, as seen in “La Dolce Vita” and “8½.” Ray, on the other hand, offered a neorealistic portrayal of Indian life, telling stories of profound humanity in films like “Pather Panchali.” Kubrick’s meticulous attention to detail and his bold narrative choices made classics like “2001: A Space Odyssey” and “A Clockwork Orange” timeless.

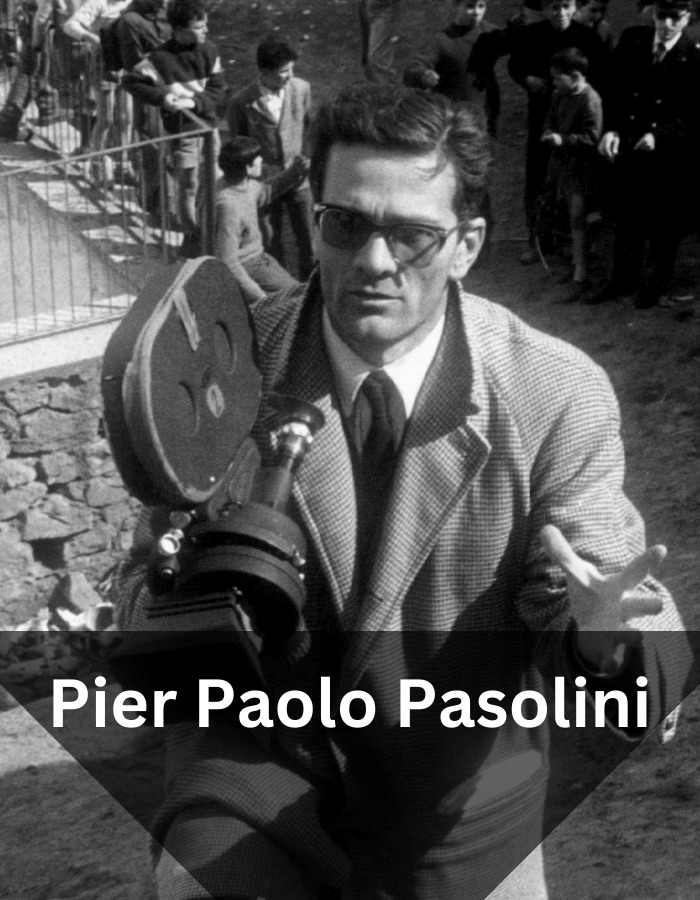

Directors like Luis García Berlanga and Pier Paolo Pasolini shared an unflinching commitment to social commentary through their films. Berlanga’s darkly comic “The Executioner” critiqued Spanish society, while Pasolini’s raw and often controversial depictions of sexuality and oppression, as in “Salo, or the 120 Days of Sodom,” were groundbreaking. Similarly, Sidney Lumet and Alan J. Pakula used the medium of film to delve into the complexities of the human condition and social issues, with Lumet’s “12 Angry Men” exploring the intricacies of justice and Pakula’s “All the President’s Men” unravelling the threads of political corruption.

The period also saw the rise of iconoclastic directors such as Sam Peckinpah and Sergio Leone, who revolutionised the Western genre. Peckinpah’s “The Wild Bunch” introduced a new level of violence and moral ambiguity to the Western. At the same time, Leone’s “The Good, the Bad and the Ugly” featured a stylised aesthetic and epic storytelling that would influence countless films.

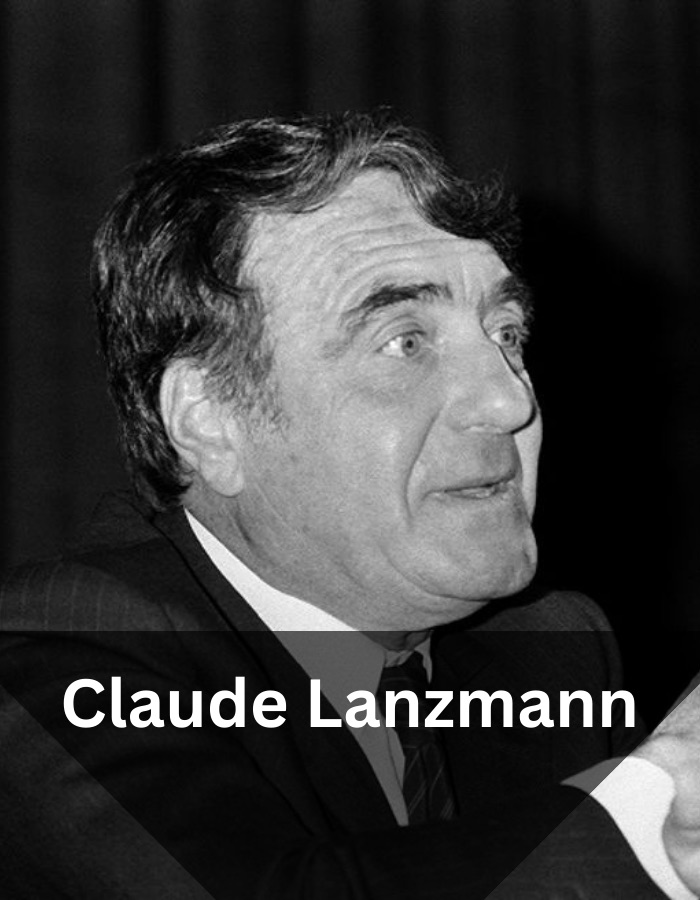

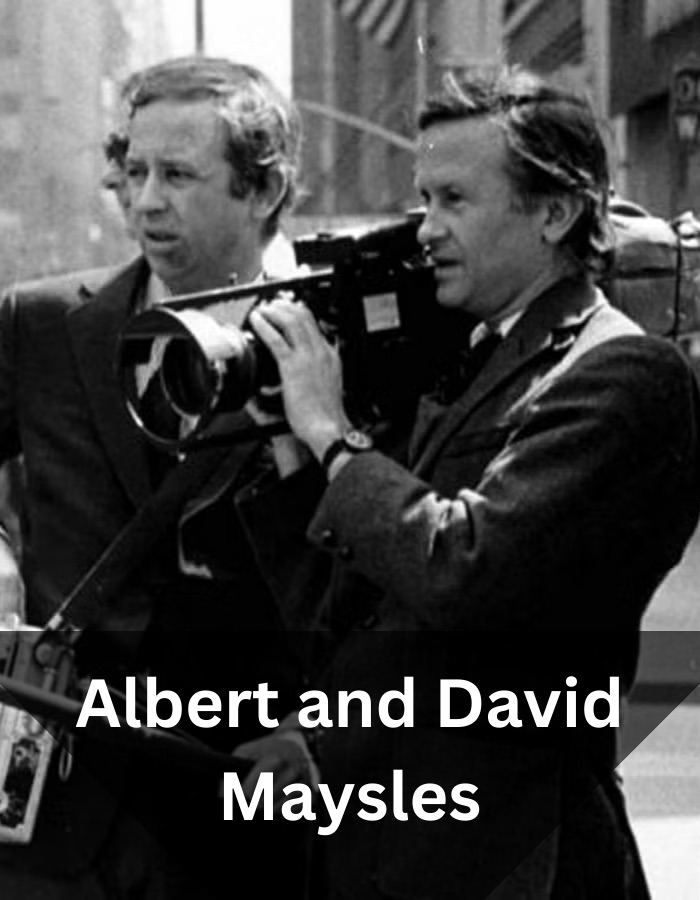

In documentary filmmaking, brothers Albert and David Maysles pioneered a direct cinema approach, as seen in “Grey Gardens,” which presented an intimate and unfiltered look into the lives of its subjects. Claude Lanzmann’s “Shoah,” on the other hand, was a monumental achievement in the representation of the Holocaust, using interviews and visits to historical sites to reconstruct the memory of the tragedy. These filmmakers shared a dedication to capturing truth on film, albeit through different methods and narrative structures.

The influence of these directors is not contained within the boundaries of their respective genres or national cinemas. Agnès Varda and Jonas Mekas, for instance, both celebrated for their contributions to French New Wave and American avant-garde cinema, respectively, utilised a personal and experimental approach to storytelling. Varda’s “Cléo from 5 to 7” and Mekas’s “As I Was Moving Ahead Occasionally I Saw Brief Glimpses of Beauty” are examples of their deeply personal, almost diaristic filmmaking styles.

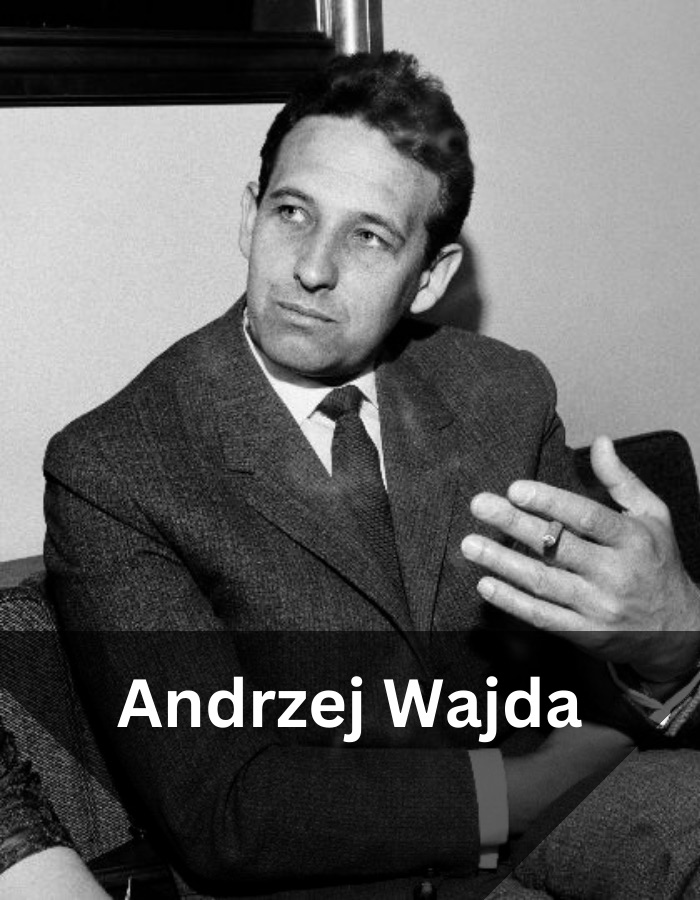

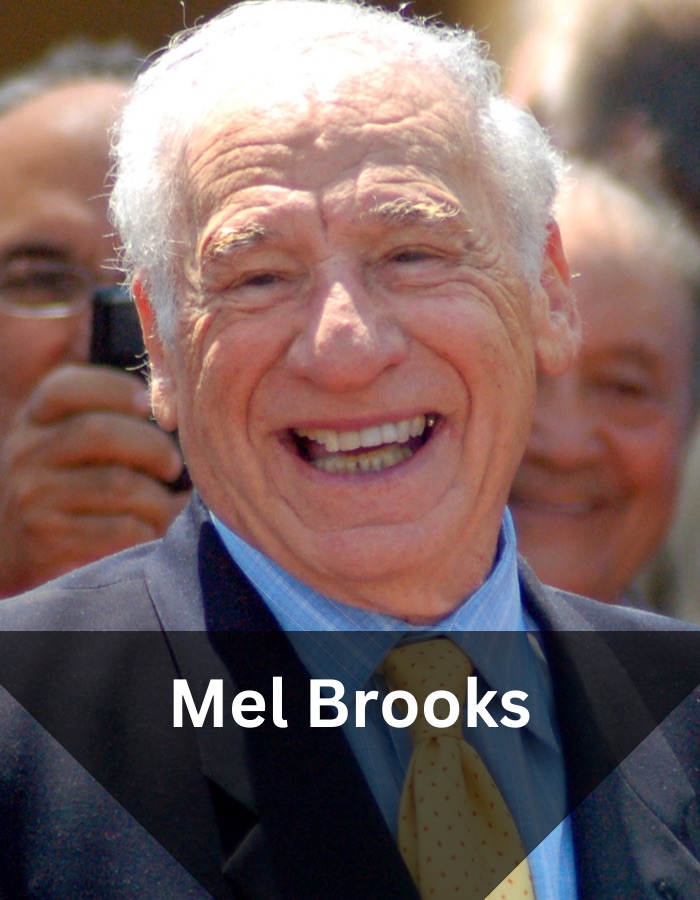

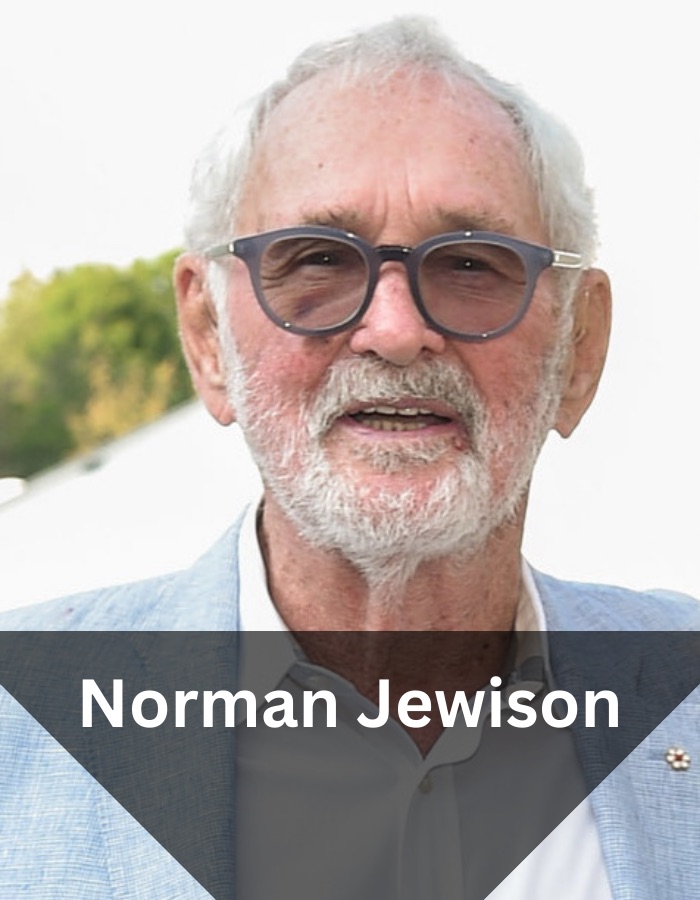

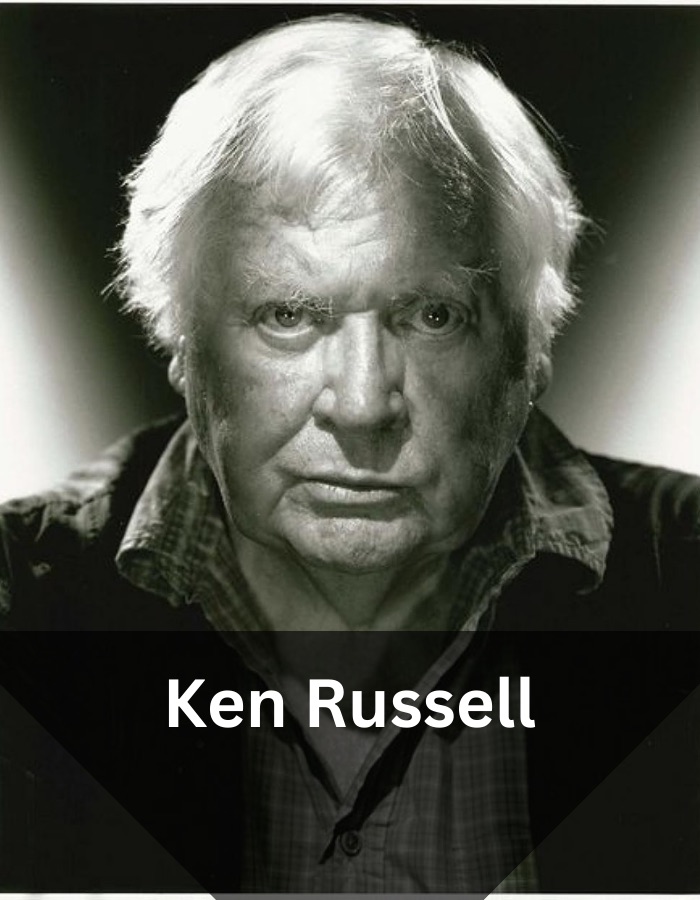

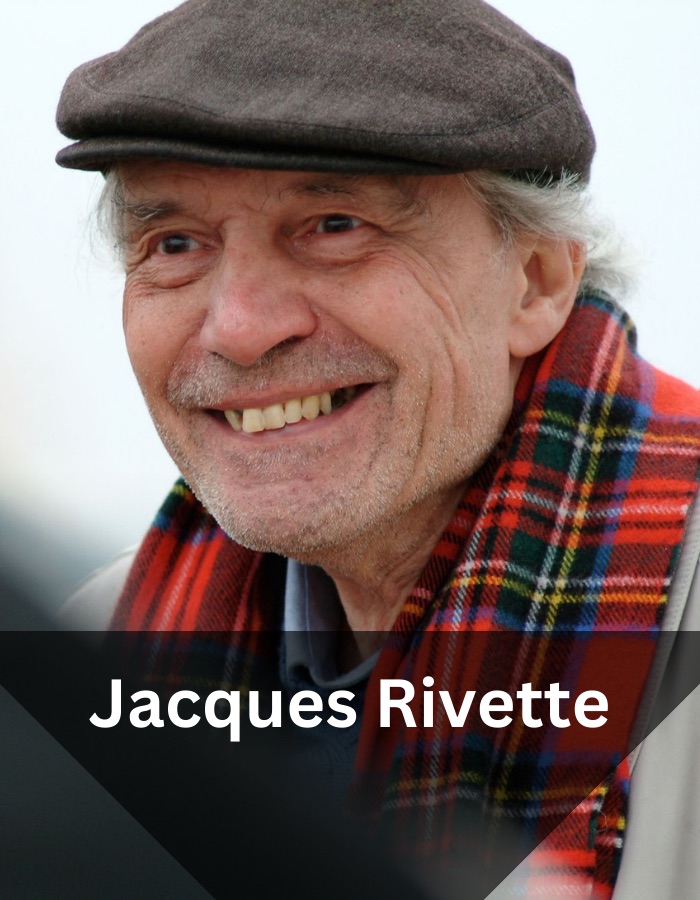

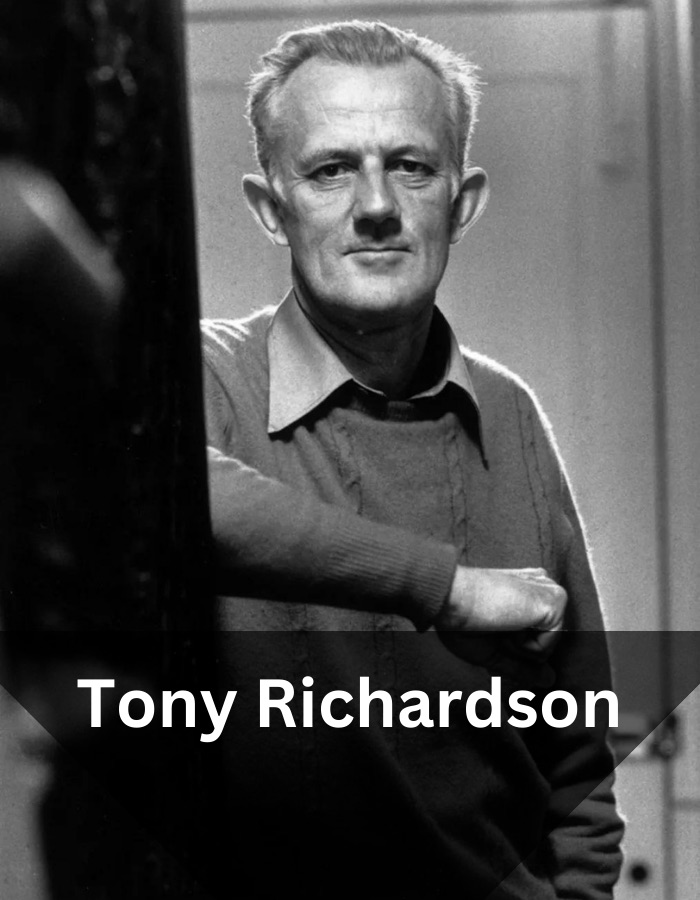

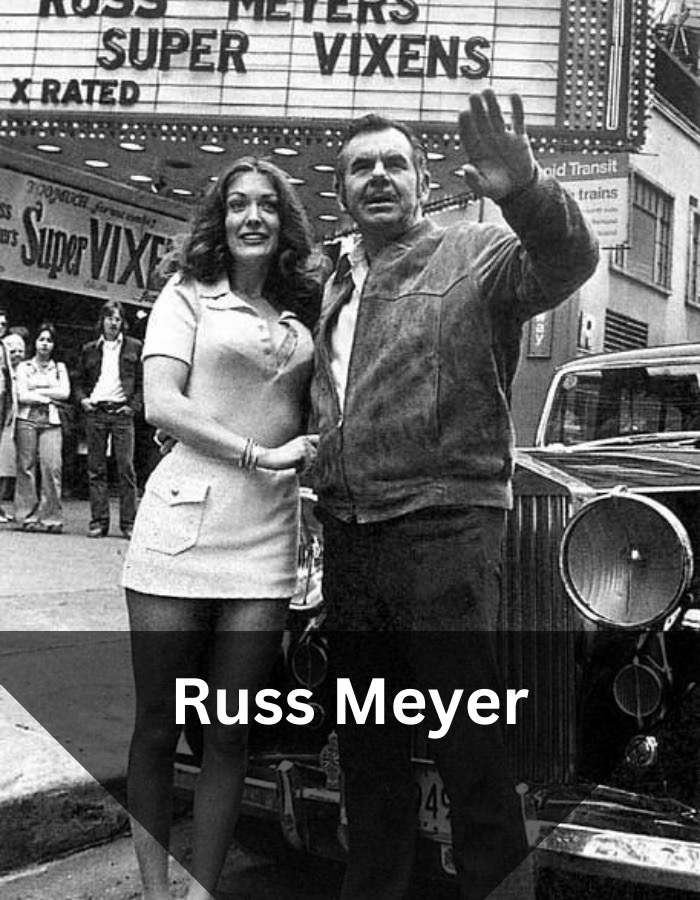

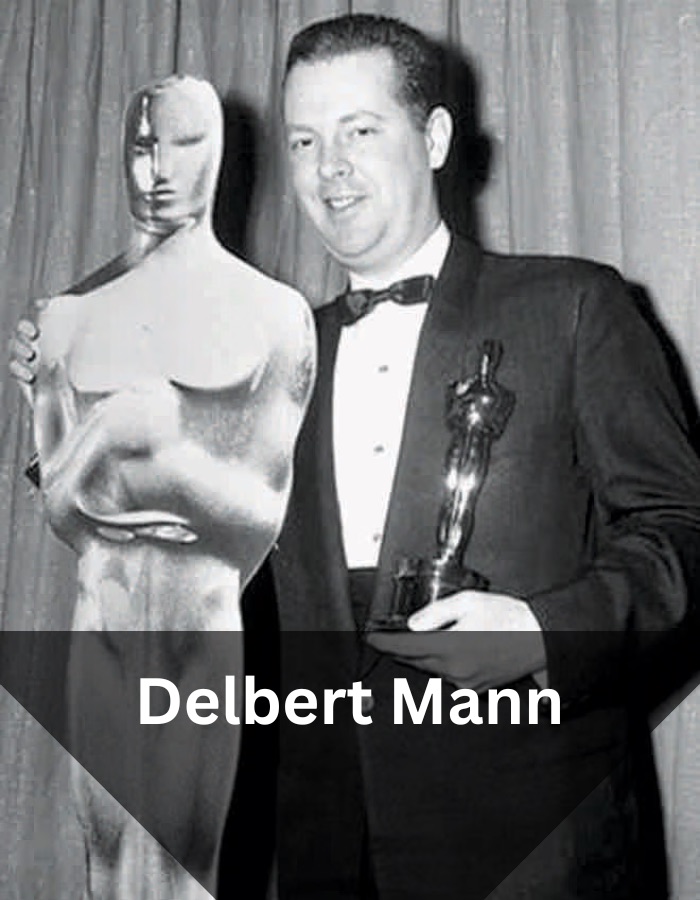

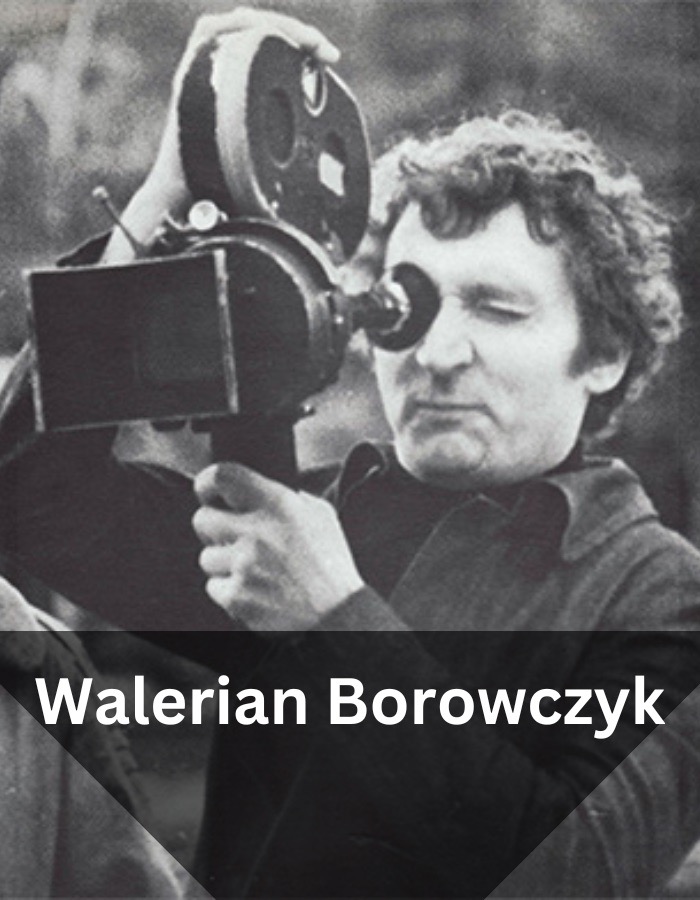

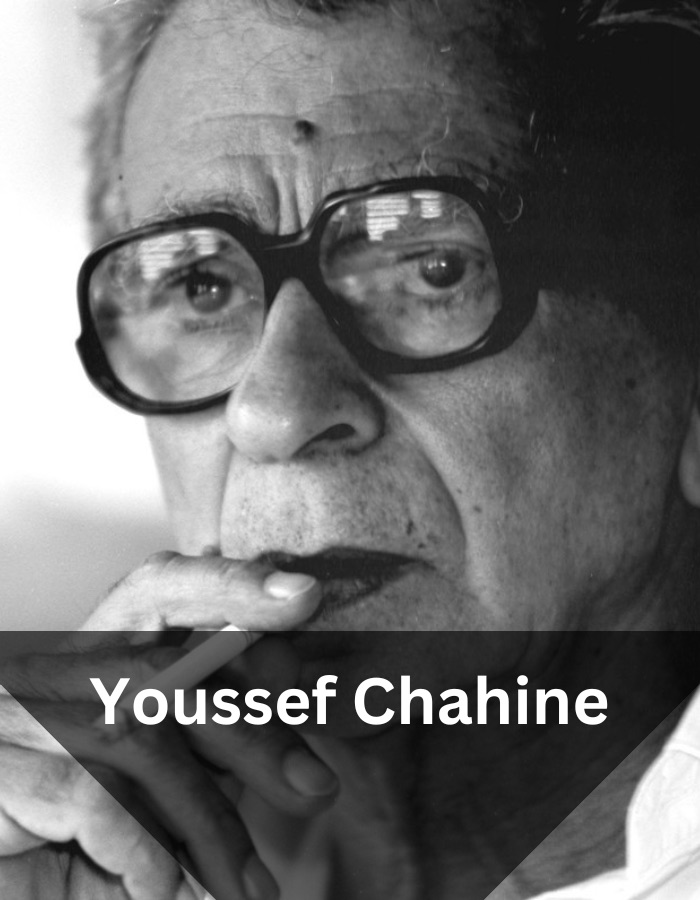

Click on the directors’ pictures to look at their profiles.