Creating a successful film is a significant accomplishment, but building a career with a series of films that showcase a unique and impactful vision is the mark of an exceptional and meticulous director. Generally, directors who achieve this don’t have the widest filmographies but are instead more selective with their work.

The challenge for filmmakers lies in avoiding repetition or engaging in projects that don’t leverage their skills. Even iconic directors like Ingmar Bergman made bad films like The Touch, and even Akira Kurosawa made his weak early efforts. The ability to consistently create and convey a unique vision, resonating with audiences each time, is a rare quality.

Some highly talented directors didn’t make this list, but those who did have played a significant role in writing and/or producing their films, solidifying their status as complete auteurs or visionary writer-directors. Even in their least successful works, these filmmakers have produced commendable and distinctive films. Presented here, in chronological order, are eleven directors who never created a subpar movie.

1. Stanley Kubrick

Stanley Kubrick’s name alone evokes a sense of awe and deep respect. Known for his meticulous craftsmanship, obsessive attention to detail, and unyielding desire to push the boundaries of cinema, Kubrick turned each of his projects into a masterpiece in its own right, avoiding making any weak films in the process.

Consider his groundbreaking work in 2001: A Space Odyssey – a film that redefined the science fiction genre and set a benchmark for visual storytelling. With its groundbreaking special effects, hauntingly beautiful score, and a narrative that spans from the dawn of man to the infinite possibilities of space, Kubrick challenged audiences to look beyond the conventional.

Or take A Clockwork Orange, with its jarring, dystopian view of society, underscored by a controversial mix of violence and classical music. Kubrick’s unflinching vision of a future gone awry struck a chord with the zeitgeist of the time, becoming a cultural phenomenon and a topic of heated debate. It’s a film that doesn’t just entertain but gnaws at your conscience, forcing you to confront the dark facets of human nature.

And who can forget the chilling corridors of The Overlook Hotel in The Shining? Kubrick transformed Stephen King’s horror novel into a deeply unsettling exploration of isolation, madness, and the supernatural. Every frame of the film is perfect, from the eerie steadicam shots navigating the hotel’s labyrinthine layout to Jack Nicholson’s iconic descent into insanity.

Kubrick’s filmography is not extensive, but each film is a universe unto itself, marked by a relentless pursuit of perfection. His reclusive nature and notorious perfectionism often led to challenging production environments, but the results are undeniable.

Yet, despite his celebrated status, Kubrick’s work often polarised critics and audiences upon initial release. He was a filmmaker ahead of his time, crafting narratives and visual spectacles that required viewers to engage, question, and interpret.

2. Robert Bresson

Robert Bresson occupies a unique, almost hallowed space. His films, characterised by a Spartan austerity and philosophical depth, stand in stark contrast to the more opulent productions of his contemporaries. It’s hard to narrow down what his best film is exactly, but “Au Hasard Balthazar” (1966) is a good guess. It’s a simple yet graceful film which uses Bresson’s minimalist style – non-professional actors, sparse dialogue, and an emphasis on sound over spectacle – to turn the ordinary into something transcendent.

Bresson’s filmography isn’t extensive, but each film is a masterclass in precision and restraint. For example, “Pickpocket” (1959) and “A Man Escaped” (1956) are not just films; they are meditations on human freedom and morality. His camera doesn’t just capture images; it peels back layers, revealing the soul of his subjects with an intimacy that can be almost uncomfortable.

Despite his critical acclaim, Bresson never quite achieved widespread popularity. His work demands patience and introspection from its audience, qualities often in short supply in the mainstream cinema landscape. This lack of broad appeal has led to a somewhat underrated status among general audiences, though he is revered by cinephiles and filmmakers who appreciate the purity of his vision.

Bresson’s later works, like “L’Argent” (1983), though less celebrated than his earlier films, continue to embody his unflinching commitment to his artistic ethos. They are stark, challenging, and uncompromising – a reflection of a man who saw film not as entertainment but as a means of exploring the depths of the human condition.

3. Federico Fellini

From the gritty streets of post-war Italy in “La Strada” to the dreamlike decadence of “La Dolce Vita,” Federico Fellini‘s films are a masterclass in blending stark realism with whimsical fantasy. His work is an intoxicating cocktail of the absurd and the profound, a mirror reflecting the human condition in all its bizarre and beautiful forms.

But, despite the acclaim, Fellini’s work often feels like an enigma wrapped in a riddle. He was a director who seemed to operate on a different wavelength, at once deeply connected to the cultural zeitgeist and profoundly isolated in his own imaginative universe. His films, like the iconic “8½,” are a labyrinth of self-reflection, exploring the psyche of the artist and the process of creation.

Fellini’s style evolved over the years, moving from the neorealism of his early work to a more personal, stylised form of storytelling. His later films, such as “Amarcord,” are like vivid dreams committed to celluloid, filled with imagery that is at once bizarrely surreal and achingly familiar. He had an uncanny ability to capture the essence of Italian life, its joys and sorrows, its beauty and vulgarity, all through a lens that was uniquely his own.

Yet, for all his celebrated genius, Fellini’s career was not without its challenges and controversies. Critics often accused him of self-indulgence, of losing touch with the raw realism that marked his early work. Some of his later films, like “Fellini Satyricon” and “Casanova,” while visually stunning, are polarising, leaving audiences and critics alike divided. While some of his films fail to live up to the expectations of his best movies, none of them are bad.

4. Andrei Tarkovsky

Born in the Soviet Union, Andrei Tarkovsky’s films were often at odds with the state’s censorship and bureaucratic limitations. This friction, however, seemed only to refine his artistic vision, creating films that were deeply personal yet universally resonant. His work, characterised by long takes and a naturalistic use of elements like fire and water, invites viewers into a contemplative space far removed from the fast-paced rhythms of conventional cinema.

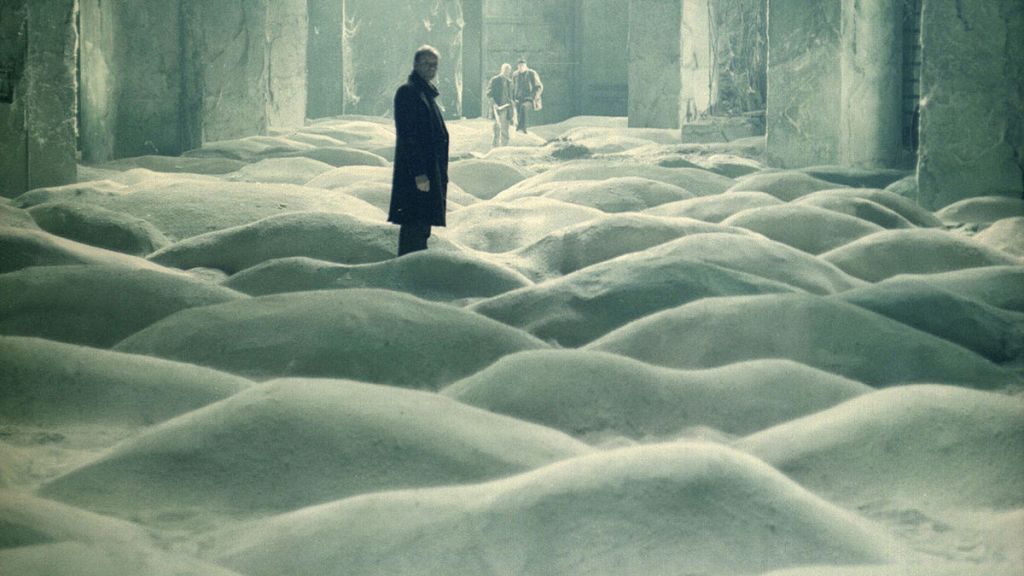

Perhaps his best film is the hauntingly beautiful “Stalker” (1979). This film transforms a post-apocalyptic landscape into a spiritual quest laden with existential questions and striking, dream-like sequences. Here, Tarkovsky’s use of colour and composition creates a world that feels at once tangible and otherworldly, a liminal space where the soul’s deepest yearnings are brought to life.

Then there’s “Andrei Rublev” (1966), an epic meditation on art, faith, and the human condition. Tarkovsky’s portrayal of the 15th-century icon painter is less a historical narrative and more a journey through the Russian soul. The film’s majestic scope and visual storytelling reveal Tarkovsky’s gift for infusing each frame with a sense of spiritual gravity.

Tarkovsky’s influence extends far beyond the Soviet borders. His impact on European cinema is profound, with his later works like “Nostalgia” (1983) and “The Sacrifice” (1986) being shot outside his homeland. These films, marked by their introspective tone and philosophical depth, explore themes of loss, longing, and redemption, resonating deeply with an international audience.

Sadly, Tarkovsky’s career was cut short by his untimely death. This meant he made just a handful of movies across his filmography, none of them being anything less than stellar.

5. Coen Brothers

The Coen Brothers, Joel and Ethan, have never made a bad film. That’s a controversial statement that will have many readers thinking, “What about The Ladykillers/Intolerable Cruelty?” But I’d argue those aren’t bad films; they’re merely less than what you’d expect from the Coens, which shows how high their standard is. Their filmography reads like a masterclass in genre-blending, effortlessly weaving between dark comedy, neo-noir, and drama with a flair that’s uniquely their own. From the bleak landscapes of Fargo to the dizzying absurdity of The Big Lebowski, they’ve carved out a niche that’s hard to define but unmistakably Coen.

Their films are an alchemy of sharp dialogue, memorable characters, and a visual style that’s both quirky and meticulous. Think of the meticulously crafted world in No Country for Old Men – a film that balances on the knife-edge of tension and philosophy. It’s a testament to their ability to transform the mundane into the profound, a skill that has often left audiences and critics alike both baffled and enamoured.

Despite their acclaim, the Coens have always maintained an air of Hollywood outsiders, perhaps by choice. They’ve never quite embraced the mainstream, even when it embraced them. Their movies, while critically lauded, often swim against the current of conventional Hollywood storytelling. They’re as unpredictable in their narrative choices as they are in their career moves – just when you think you’ve pinned them down, they pivot, surprising even their most ardent fans.

Their versatility is another point of distinction. From the existential comedy of A Serious Man to the vintage Hollywood homage in Hail, Caesar!, they demonstrate an uncanny ability to hop genres without missing a beat. Yet, no matter the story, their films are imprinted with an unmistakable Coen watermark – a blend of cynicism, humour, and a deep-seated understanding of the human condition.

6. Denis Villeneuve

Certainly, one of the newer directors on the list, Denis Villeneuve, a visionary from the snowy landscapes of Quebec, has emerged as one of the most compelling filmmakers right now. It might be a bit preemptive to say he’s never made a bad film, but even his earliest gritty Canadian films have something to them. Something he’s not lost in the transition to Hollywood.

Take, for instance, his 2016 film Arrival, a poignant exploration of language and time wrapped in the guise of a sci-fi drama. Villeneuve carefully constructs each frame; the slow-burning tension and the profound meditation on the human condition elevate the film far beyond its alien encounter premise.

Then there’s Blade Runner 2049, a sequel to Ridley Scott’s masterpiece, which in lesser hands might have faltered under the weight of its legacy. Yet, Villeneuve not only honours the original but expands its universe with a visually stunning and emotionally resonant narrative. His Blade Runner is not just a technical marvel but a deeply philosophical journey exploring themes of identity and reality.

Despite his ascent in Hollywood, Villeneuve has maintained an auteur’s touch, never losing sight of the human element amidst his films’ grandiose settings. A haunting beauty, a lingering sense of melancholy, and a contemplative approach to storytelling mark his works. Each film feels like a tapestry of human emotions woven against the backdrop of larger-than-life narratives. It’s certainly possible that Villenueve’s quality will get derailed, but right now, he’s never made a bad film.

7. Bong Joon-ho

With the ever so minor exception of his debut film, Barking Dogs Never Bite, none of Bong-Joon Ho’s films have been anywhere close to poor; even Barking Dogs has its fans. Emerging as a significant voice in the South Korean New Wave, Bong has crafted a filmography that’s as diverse as it is impactful, marked by a sharp wit and a keen eye for the absurdities of human nature.

His breakout film, Memories of Murder, is a masterclass in balancing the grim realities of a serial killer investigation with moments of dark humour. This film, like much of his work, refuses to be pigeonholed into a single genre. Bong’s talent lies in this very ability to defy expectations, blending horror, comedy, and drama in a way that feels uniquely his own.

Perhaps the pinnacle of Bong’s international acclaim came with Parasite, a film that not only won the Palme d’Or but also swept the Oscars in a historic first for a non-English language film. Parasite is a scathing commentary on class disparity, wrapped in the guise of a family drama that morphs into a suspenseful thriller. The film’s success is a testament to Bong’s skill in crafting stories that resonate across cultural boundaries, conveying universal truths through distinctly Korean lenses.

Bong’s directorial style is marked by his meticulous attention to detail and a penchant for sudden tonal shifts that keep the audience on their toes. His films are visually striking, often using space and architecture to enhance the narrative. From the cramped semi-basement apartment in Parasite to the dystopian train in Snowpiercer, his settings are characters in their own right, contributing to the film’s broader social and political themes.

8. Hayao Miyazaki

Hayao Miyazaki holds a unique place in the hearts of movie fans, hovering somewhere between a household name and a cult icon. His work, primarily under the banner of Studio Ghibli, has awed audiences with the whimsical flights of My Neighbor Totoro and the depths of Spirited Away.

Miyazaki’s genius lies in his ability to blend the fantastical with the deeply personal. His films are embroidered with themes of environmentalism, pacifism, and the complexities of human nature, all while maintaining a sense of wonder and enchantment. He crafts narratives that resonate with both children and adults, navigating through them with a kind of poetic grace that’s rare in cinema. There’s a timeless quality to his work, as if his films exist in a realm of their own, untouched by the changing tides of movie trends.

Consider the breathtaking flight scenes in Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind or the serene, almost melancholic beauty of The Wind Rises. These moments are not just visually stunning; they are deeply evocative, nearly spiritual experiences. Miyazaki’s animation style, with its meticulous attention to detail and its fluid, almost dreamlike quality, has become iconic, influencing not just other animators but filmmakers in general. If you were to ask ten fans which films of his they’d call the weakest, you’d get ten different answers. It’s a testament to the near-perfect filmography he’s created.

9. Quentin Tarantino

We all know and love Quentin Tarantino. He isn’t just another director. He’s a fiery, audacious director whose work is a frenzied amalgamation of homage, innovation, and outright cinematic rebellion.

Tarantino’s approach to filmmaking is akin to a master chef who knows all the classic recipes by heart but insists on adding his unique twist. He borrows from spaghetti westerns, samurai cinema, and 70s exploitation films, yet his output is unmistakably original. His knack for snappy, pop-culture-infused dialogue and non-linear storytelling has made his style instantly recognisable and widely imitated, yet never quite replicated.

How about the iconic dance scene in “Pulp Fiction” or the tense standoffs in “Django Unchained.” Tarantino’s scenes are more than mere narratives; they’re visceral experiences that stay etched in the viewer’s memory. His use of music is masterful, turning obscure tracks into iconic soundscapes that define entire sequences. He doesn’t just tell stories; he crafts universes where every character, no matter how minor, has a life of their own.

Yet, Tarantino’s career is also marked by controversy. His unabashed use of violence and language has been both lauded and criticised. He’s a director who refuses to play it safe, pushing boundaries and challenging audiences. His films are a roller coaster of emotions, often leaving viewers exhilarated, shocked, and sometimes uncomfortable. These controversies, however, don’t mean these films are bad. Not at all, as even his weakest movie, Death Proof, is a fiery, awesome film.

10. Paul Thomas Anderson

What’s Paul Thomas Anderson’s worst film? Is it Inherent Vice? Maybe, but even that’s a cult classic. PTA burst onto the scene in the late 90s with “Boogie Nights,” a dazzling, kinetic exploration of the porn industry in the 1970s. The film showcased his ability to create rich, multi-dimensional worlds filled with flawed yet deeply human characters. Ever since then, he’s only made great films.

After Boogie Nights came “Magnolia,” a sprawling, ambitious tapestry of interwoven stories. If ever PTA was going to make a bloated bad film, it was now, yet. Instead, he cemented his reputation as a filmmaker unafraid to tackle grand themes and narratives. The film’s raw emotional power and narrative complexity demonstrated an artist hitting his stride, unafraid to push boundaries.

However, it’s perhaps with “There Will Be Blood” that Anderson truly ascends to the pantheon of great American directors. A searing, epic tale of ambition, madness, and the birth of modern America, the film is a tour de force of storytelling and cinematic craft. Daniel Day-Lewis’ towering performance, combined with Anderson’s precise direction, creates a cinematic experience that’s both haunting and unforgettable.

Yet, despite these triumphs, Anderson remains something of an enigma. His films, like “The Master” and “Phantom Thread,” are critically acclaimed and fiercely debated, yet they often eschew mainstream appeal for a more cerebral, introspective approach. This has made Anderson a darling of film critics and cinephiles but somewhat elusive to the wider public.

11. Sergio Leone

Sergio Leone only directed seven films in his lifetime. It’s a shockingly low number for someone of his talent. He was a meticulous director whose films, which seemingly centred around the arid deserts and ruthless outlaws of the American West, transcended mere genre definitions.

Think of the iconic opening scene in “The Good, the Bad and the Ugly”. The meticulous composition, the lingering close-ups that capture every rugged crease on the character’s faces, the haunting score by Ennio Morricone – it’s all Leone’s signature style. His ability to craft a narrative not just through dialogue but through visuals, music, and an almost palpable tension is nothing short of masterful.

Leone’s films were more than just Westerns; they were cinematic operas, grand in scale and rich in detail. His storytelling was not about the rush of action but the suspenseful build-up – the long, silent moments that explode into brief, violent encounters. It’s in these moments that Leone’s talent shines brightest, transforming what could have been mundane showdowns into unforgettable cinematic events.

His influence extends beyond the Western genre, inspiring filmmakers across various styles and eras. Quentin Tarantino’s work, for example, echoes Leone’s penchant for drawn-out scenes and sudden bursts of violence. Yet, despite this influence, Leone’s own career was a curious blend of monumental successes and periods of silence, often struggling with the commercial film industry, choosing instead to follow his unique vision.

Leone’s later years saw a shift away from Westerns, most notably with “Once Upon a Time in America”, a sprawling crime saga that cemented his status as a master storyteller. However, much like many of art’s greats, Leone’s potential was never fully realised, his career cut short by his untimely death.