May 1968 was the death knell of the French New Wave. You could claim it had ended earlier, but people weren’t aware of that fact until the events of May when the barricades went up, and Paris was engulfed in protests. The spirit of rebellion wasn’t confined to the streets. The French New Wave, with its radical techniques, its breezy disregard for classical cinematic norms, and its intimate character studies, seemed suddenly to belong to a more innocent era. Directors like Jean-Luc Godard, François Truffaut, and others who had once been the enfants terribles of cinema found themselves at a crossroads. Their films, which had been the epitome of modernity and rebellion, now appeared quaint against the backdrop of a society in the throes of a real revolution.

Godard, in particular, took a radical turn towards more politically charged cinema, reflecting the tumult of the times. The whimsical charm of À bout de souffle (Breathless) gave way to the more somber and ideologically driven works like La Chinoise.

As the dust settled, French cinema found itself transformed. The playful experimentation with form and narrative, the iconoclastic spirit, and the sheer joie de vivre of the New Wave were replaced by a cinema more directly engaged with the pressing social and political issues of the day. The old names founds themselves displaced and new voices started to emerge.

The Zanzibar Group

As the French New Wave crested and broke upon the shores of a new era, a fresh breed of cinematic provocateurs emerged from the tumult. The Zanzibar Group, a loose collective of radical young French filmmakers, artists, actors, and technicians, attempted to take the baton from their New Wave predecessors and sprinted towards uncharted territories of cinematic expression.

Active from 1968 to 1970, the Zanzibar Group included luminaries such as Philippe Garrel, Jackie Raynal, Patrick Deval, Daniel Pommereulle, Serge Bard, Caroline de Bendern, and Zouzou, among others. This eclectic band of creatives was united not only by their passion for cinema but also by the patronage of heiress Sylvina Boissonnas. Boissonnas provided the financial backing for the group to shoot films on 35mm with virtually no oversight or restrictions, granting them an unprecedented level of creative freedom.

Many members of the Zanzibar Group had dropped out of college to start making films, eager to leave their mark on the cinematic landscape. The group was a diverse mix of talents, including editors like Jackie Raynal (who had worked with Eric Rohmer), conscientious objectors like Daniel Pommereulle, and future anthropologists like Serge Bard. Several members, such as Pierre Clémenti and Juliet Berto, went on to have notable acting careers.

The moniker “Zanzibar” originated from a planned 1969 trip that some members embarked upon, intending to traverse Africa and reach Zanzibar, which was then a Maoist state – Maoism being a cornerstone of the events of May 1968. However, the journey was cut short when Serge Bard experienced a spiritual awakening and converted to Islam, leading to the abandonment of the expedition.

Beyond their movies, the Zanzibar Group was characterised by an air of dandyism and a keen sense of style. All members were known for their fashionable appearances, with Caroline de Bendern and Zouzou even working as professional models. The group’s aesthetic blurred the lines between cinema, visual art, and fashion, creating a unique sensibility that set them apart from their contemporaries.

Influences of the Zanzibar Group

The Zanzibar Group drew inspiration from various sources. The poet and art critic Alain Jouffroy was a crucial mentor for many of the group’s members, guiding their artistic development. The group’s films were also heavily influenced by Jean-Luc Godard and the American underground cinema scene.

The group had connections to the French New Wave, American underground film, and Andy Warhol‘s Factory, with some members having collaborated with or visited those scenes. They also worked with renowned cinematographers like Henri Alekan, known for his work on films such as Jean Cocteau‘s Beauty and the Beast.

Like the French New Wave before them, the Zanzibar Group’s work rejected the “cinéma de papa” (daddy’s cinema) and the mainstream film industry. They sought to create a new cinematic language unfettered by traditional filmmaking conventions and restrictions.

Sylvina Boissonnas: The Patron Saint of the Zanzibar Group

At the heart of the Zanzibar Group’s meteoric rise and brief, brilliant existence was Sylvina Boissonnas, a young French heiress and patron of the arts. Boissonnas’ financial backing and unconventional approach to film production were key factors in enabling the group’s members to create groundbreaking works with an unparalleled level of artistic freedom.

Boissonnas streamlined the production process, eschewing contracts with directors and forgoing payment for actors. This maverick approach allowed the Zanzibar Group to operate outside the confines of the traditional filmmaking system, creating a space for truly renegade productions. The films were made without scripts, and all except one were shot using expensive 35mm film, a testament to Boissonnas’ commitment to the group’s artistic vision.

In selecting projects to finance, Boissonnas prioritised aesthetic considerations over the filmmakers’ experience or reputation. This unconventional approach opened the door for a new generation of cinematic voices, many of whom might have been overlooked by the mainstream film industry. Boissonnas’ patronage was crucial in allowing the group complete artistic freedom to experiment with the 35mm format, drawing parallels to earlier avant-garde collectives.

Boissonnas’ approach to financing films was reminiscent of the Vicomte and Vicomtesse de Noailles, who funded avant-garde films like Luis Buñuel‘s L’Âge d’Or in the 1930s. Like the Noailles, Boissonnas recognised the importance of supporting innovative and challenging works of art, even if they existed outside the mainstream.

Sylvina Boissonnas’ family background likely significantly influenced her decision to finance the Zanzibar Group’s projects. Her mother and aunt were both prominent art patrons, and Boissonnas grew up in an environment that valued and supported artistic expression. This upbringing undoubtedly influenced her decision to use her wealth to support the avant-garde filmmakers of the Zanzibar Group.

What Makes a Movie a “Zanzibar Film”?

The Zanzibar Group’s films were a product of their time, born out of the revolutionary spirit of May 1968 in France. These poetic, aesthetically avant-garde works served as an ethical manifesto, challenging the conventions of traditional cinema and calling for a new approach to filmmaking.

The group’s approach borrowed heavily from underground and experimental filmmaking, eschewing meaningfulness in favour of spontaneity and provocation. The films were shot quickly using minimal resources, resulting in an aesthetic of nakedness and radicalism. This raw, unpolished style was a deliberate choice, a rejection of the polished, commercially driven films of mainstream cinema.

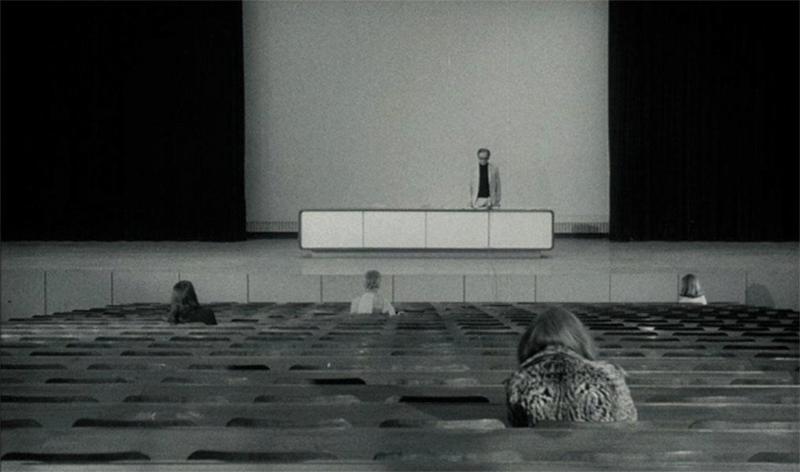

One of the defining characteristics of the Zanzibar films was their visual experimentation. Serge Bard’s films Ici et Maintenant and Fun and Games for Everyone, for example, used high-contrast black-and-white cinematography to create striking, almost surreal images. The group’s work was also marked by minimal editing, a lack of sync sound and dialogue, and nonlinear, dream-like narratives that prioritised powerful visuals over coherent storytelling.

The Zanzibar films often featured panoramic shots that left viewers to find their own focal points, quasi-improvised dialogue, or, in many cases, almost no dialogue at all. This minimalistic approach to sound reflected the group’s appreciation for silent cinema and the visual power of images. By stripping away the crutch of dialogue, the Zanzibar filmmakers forced viewers to engage with their works on a purely visual level.

Made quickly and cheaply, often without full scripts and with unpaid actors, the Zanzibar films were a testament to the power of experimentation and the potential of cinema as a medium for political and artistic expression. Between 1968 and 1970, the group produced around 13-15 films, each one a unique exploration of the boundaries of the medium.

The goal of the Zanzibar films was not to entertain but to challenge. By rejecting conventional narrative and technique in favour of spontaneity and provocation, the group sought to confront viewers, shake them out of their complacency, and force them to reconsider their assumptions about what cinema could be.

In the end, what makes a movie a “Zanzibar film” is not any single aesthetic or narrative choice, but rather a spirit of experimentation, a willingness to take risks, and a deep commitment to cinema’s transformative power.

Politics and Philosophy of Philippe Garrel & the Zanzibar Group

At the forefront of the Zanzibar Group was Philippe Garrel, a young filmmaker whose work and philosophy embodied the revolutionary spirit of the late 1960s. In April 1968, at the age of 20, Garrel’s first feature film, Marie Pour Mémoire, won the top prize at the fourth annual festival of young cinema at Hyères.

In his acceptance speech, Garrel made a bold declaration that foreshadowed the events to come: he was fed up with cinema, and what interested him now was prophecy. He proclaimed that if his film were to have any value, it should be like a cobblestone hurled into the cinema. This vision became a reality on the barricades in the Latin Quarter during the tumultuous events of May 1968.

The Zanzibar Group’s films were inherently political in their artistic, convention-destroying act. The consciousness of cinema prevailed over the cinema of consciousness as the group sought to challenge societal norms and hierarchies through their work. Serge Bard’s film Détruisez-Vous, titled after a graffito meaning “Help us, destroy yourselves,” anticipated the revolutionary fervour of May 1968, while Patrick Deval’s film Acéphale, named after Georges Bataille’s journal, suggested a desire to move beyond rational thinking.

The Zanzibar films were a reaction against the perceived bourgeois nature of mainstream cinema, echoing the anti-authoritarian philosophy of Joseph Beuys, who advocated for open admission to art academies. The group’s approach to filmmaking was also influenced by the idea of “destroying the society of the spectacle,” as proposed by Guy Debord and the Situationist International.

The Zanzibar movement was in sync with the youth movements in the United States and the perceived cultural revolution in China during the late 1960s. The group sought to implement a collective management style and reject authority delegation, reflecting the anarchist and anti-hierarchical sentiments of the time.

Major Zanzibar Group Movies

A group’s ideals are all well and good, but they’re ultimately a bit useless if they don’t have something to back them up. The Zanzibar Group never really made a canonical film. Still, in the grand scheme of things, that makes sense as their “film tracts”, a reference to the revolutionary pamphlets of May ’68 were not intended for mainstream audiences or distribution but rather served as artistic and political statements.

Among the major Zanzibar films were Serge Bard’s Détruisez-vous, Jackie Raynal’s Deux Fois, Philippe Garrel’s Le Révélateur and La Cicatrice Intérieure, Patrick Deval’s Acéphale, and Daniel Pommereulle’s Vite. Each of these films, in its unique way, pushed concepts of moviemaking and challenged viewers to reconsider their assumptions about the medium.

Philippe Garrel’s films are the most watched and the best remembered of the group. He made several films during this period, including Le Révélateur, La Concentration, Le Lit de la Vierge, and La Cicatrice Intérieure. These films, often featuring Nico from Andy Warhol’s Factory as Garrel’s muse, represented a movement toward introspection and a drug-influenced aesthetic.

Garrel’s approach to filmmaking involved finding a place and time, treating it as the centre of the world for his cast and crew, and allowing the excitement of the camera to capture the rest. He preferred shooting long takes that made up the building blocks of his films, avoiding editing and enabling the shots to fit into a logical, intuitive continuity. For Garrel, filmmaking was not about telling stories or having characters symbolise a class or ideal but rather about the physical act of capturing a moment in time.

Meanwhile, other members challenged the medium’s limits. Jackie Raynal’s film Deux Fois challenged traditional notions of narrative and causality, with scenes repeated multiple times without clear explanation. Daniel Pommereulle’s Vite went to space, with images of the galaxy captured using a Questar telescope attached to a movie camera.

While most of the group left Cinema after 1970, Philippe Garrel has frequently returned to explore the themes and events of May ’68 in his later works, such as Les Amants Réguliers, demonstrating the lasting influence of that tumultuous period on his artistic vision.

Brief Outline of Zanzibar Group Films

Deux Fois (1968) – Jackie Raynal

Jackie Raynal’s Deux Fois is a mesmerising and enigmatic work that challenges traditional notions of narrative and temporality. The film consists of a series of seemingly disconnected scenes, each repeated twice, with Raynal herself appearing on screen to announce the repetitions. This unconventional structure creates a sense of déjà vu and invites the viewer to reconsider their understanding of cause and effect, linearity, and the construction of meaning in cinema.

Le Revelateur (1968) – Philippe Garrel

Le Revelateur is a haunting and surreal silent film that follows a young couple and their child as they navigate a desolate, post-apocalyptic landscape. Shot in stark black and white, the film relies on powerful imagery and the expressive performances of its actors to convey a sense of alienation, despair, and the search for meaning in a world stripped of certainty.

Acephale (1968) – Patrick Deval

Acephale is a provocative and unsettling film that takes its title from Georges Bataille’s concept of the “headless” man, a being who has transcended the limits of rational thought. The film follows a group of young people living on the margins of society, their actions and interactions captured through a combination of direct address to the camera and obscure, symbolic performances.

The Virgin’s Bed (1969) – Philippe Garrel

In The Virgin’s Bed, Philippe Garrel offers a deeply personal and allegorical reflection on the events of May ’68 and the role of the artist in times of political turmoil. The film stars Zouzou as a figure embodying both the Virgin Mary and Mary Magdalene, opposite Pierre Clémenti as a Christ-like character who has abandoned his revolutionary ideals in the face of the world’s cruelty. Through its poetic imagery and non-linear structure, The Virgin’s Bed grapples with themes of disillusionment, sacrifice, and the search for meaning in the aftermath of a failed revolution.

Destroy Yourself (1969) – Serge Bard

Shot in the lead-up to the events of May ’68, Destroy Yourself serves as a call to action, urging viewers to reject bourgeois society’s conformity and complacency and embrace radical, transformative politics. Through its jarring imagery and unconventional approach to narrative and character, Destroy Yourself captures the sense of urgency and unrest that characterised the late 1960s.

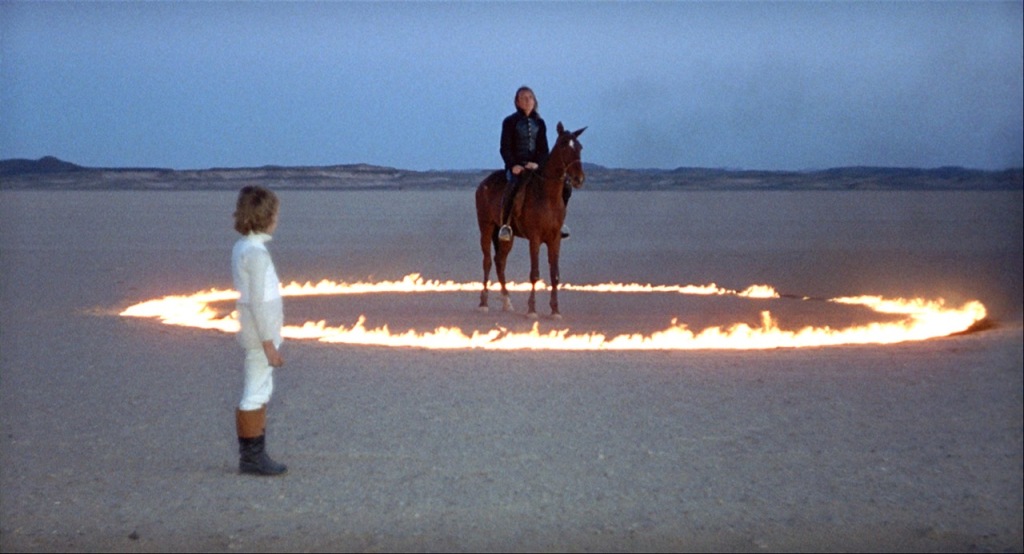

The Inner Scar (1972) – Philippe Garrel

While not technically a Zanzibar film, Philippe Garrel’s The Inner Scar is a deeply personal and introspective work that represents a continuation of the themes and aesthetics he explored during his time with the group. Starring Nico, the film is a meditation on love, loss, and the struggle to find meaning in the face of personal and political disillusionment. Through its striking imagery, haunting soundtrack, and intimate performances, The Inner Scar showcases Garrel’s growth as a filmmaker and his ongoing commitment to using cinema as a means of self-expression and philosophical inquiry.

The Death of the Zanzibar Group

As quickly as it emerged, the Zanzibar Group dissolved, its brief but curious existence ending around 1970-71. The primary catalyst for the group’s demise was the withdrawal of financial support from Sylvina Boissonnas, who had been the driving force behind the collective’s ability to create groundbreaking works. As Boissonnas moved on to other interests, such as feminism, the Zanzibar filmmakers found themselves without the resources to continue their unconventional approach to cinema.

Most of the group’s members also moved on to other pursuits, with Philippe Garrel being the main figure to continue making notable films in the years that followed. Jackie Raynal, who had directed the Zanzibar film Deux Fois, later became known as the programmer of the Carnegie Hall Cinema and the Bleecker Street Cinema in New York City.

Despite the group’s dissolution, Boissonnas attempted to secure a future for the Zanzibar films by exploring various distribution and exhibition options. She sought to sell the rights to the movie to an American distributor and even considered purchasing a cinema in Paris to screen them. However, these plans ultimately did not come to fruition, and the films, which intentionally lacked credits and refused commercial distribution, remained largely unknown for decades.

It wasn’t until a retrospective at the Cinémathèque Française in 2000 that the Zanzibar films were rediscovered and recognised as important works of the post-May ’68 era. This renewed interest revealed the significance of the Zanzibar movement as a bridge between the French New Wave and the underground/experimental film scene of the late 1960s, with its members’ works embodying the fusion of radical politics and avant-garde aesthetics that characterised the period.

The Zanzibar Group’s legacy, despite its short existence, lies in its role as a representation of the revolutionary spirit that permeated the arts in the wake of May 1968. The group’s uncompromising approach to filmmaking, its rejection of commercial viability and mainstream conventions, and its embrace of experimentation and political engagement have influenced countless filmmakers in the decades since.

For a similar lesser-told story about French Cinema, check out The Mac-Mahon Cinema – France’s Other Critics.

Sources

1 – https://www.theguardian.com/film/2002/feb/09/books.guardianreview

2 – https://www.gartenbergmedia.com/the-zanzibar-films

3 – https://www.artforum.com/features/no-wave-the-zanzibar-group-188145/