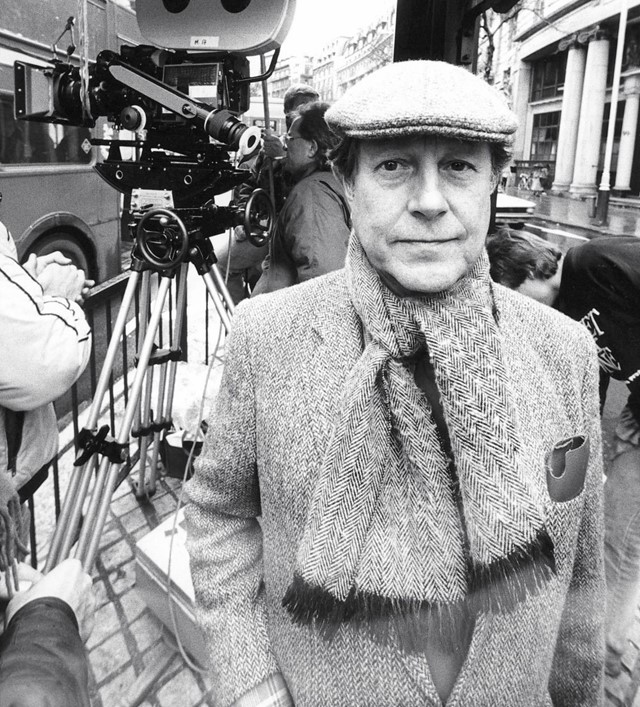

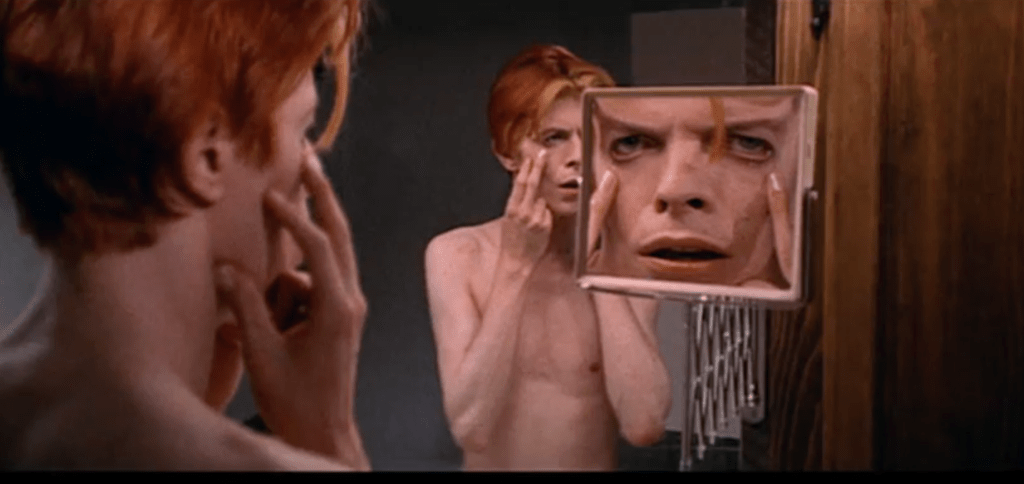

Nicolas Roeg was a trailblazing British filmmaker revered for his innovative visual style and narrative approach. Known for his bold colour compositions and unique storytelling techniques, Roeg’s body of work often delves into psychosexual themes and explores the darker facets of human nature. His films, like Don’t Look Now and Bad Timing, blazed new trails in cinema, pushing the boundaries of narrative structure and thematic exploration. Roeg’s collaborations with musicians, like David Bowie in The Man Who Fell to Earth and Mick Jagger in Performance, added another layer of uniqueness to his oeuvre, and many of his films have attained cult status.

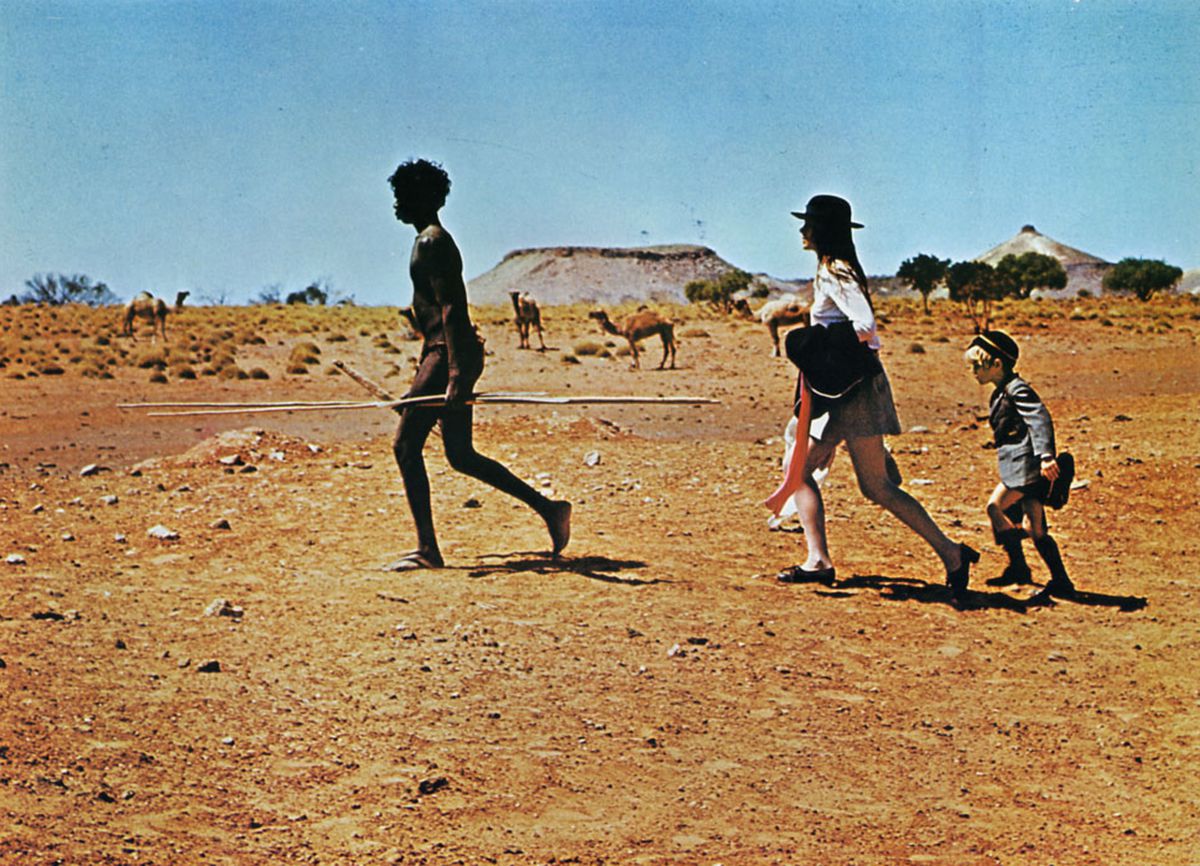

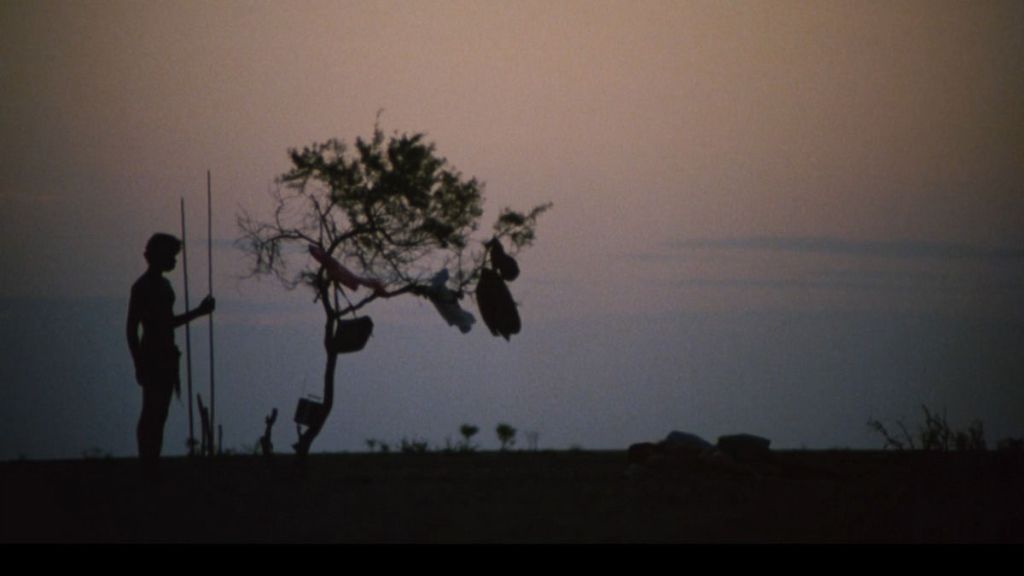

Roeg began his career in cinematography, working as the Director of Photography on films like Fahrenheit 451 and Far from the Madding Crowd. This background heavily influenced his directorial style and his approach to visual storytelling. His use of colour and composition to enhance the mood and themes of his films is evident in Walkabout, where the Australian outback’s vibrant hues accentuate the narrative’s stark contrasts. Similarly, Don’t Look Now uses its Venetian setting’s colour palette and labyrinthine design to mirror the protagonists’ emotional turmoil and disorientation.

Roeg’s films are known for their non-linear narrative structure, offering a complex, layered exploration of their subjects. Films like Bad Timing break traditional storytelling norms, utilising time jumps and flashbacks to weave a dense psychological tapestry. Similarly, his work often incorporates supernatural and mystical elements, blurring the lines between reality and fantasy. In The Man Who Fell to Earth, for instance, Roeg explores a humanoid alien’s alienation in a literal and metaphorical way, offering a critique of human society.

Despite their often controversial reception upon release, Roeg’s films are revered for their audacious style, thematic depth, and innovative narrative techniques. Many found his work obtuse or unsettling, yet these very aspects have since garnered praise. Initially deemed obscure and disturbing, films like Performance are now celebrated as groundbreaking works, reflecting Roeg’s penchant for challenging cinematic conventions.

Roeg’s influence on cinema is both national and international. His bold stylistic choices and narrative innovations have inspired a range of directors, from Danny Boyle in the UK to Alejandro González Iñárritu in Mexico. Even Christopher Nolan, renowned for his own complex narrative structures, has acknowledged the influence of Roeg’s films. Through his distinctive cinematic language, Roeg left an indelible mark on film history, affirming his place as one of the most audacious filmmakers of his time.

Nicolas Roeg (1928 – 2018)

Calculated Films:

- Performance (1970)

- Walkabout (1971)

- Don’t Look Now (1973)

- Bad Timing (1980)

Similar Filmmakers

Nicolas Roeg’s Top 10 Films Ranked

1. Walkabout (1971)

Genre: Coming-of-Age, Adventure, Drama, Survival

2. Don’t Look Now (1973)

Genre: Psychological Thriller, Mystery

3. Bad Timing (1980)

Genre: Psychological Drama, Mystery

4. Performance (1970)

Genre: Psychological Drama, Gangster Film

5. The Man Who Fell To Earth (1976)

Genre: Sci-Fi, Drama, Extraterrestrial

6. Insignificance (1985)

Genre: Drama, Satire, Alternative History

7. The Witches (1990)

Genre: Fantasy, Family

8. Eureka (1983)

Genre: Drama

9. Track 29 (1988)

Genre: Psychological Drama, Mystery

10. Two Deaths (1995)

Genre: Drama

Nicolas Roeg: Themes and Style

Themes:

- Dislocation and Alienation: Roeg’s films often explore characters who are out of sync with their surroundings, as seen in The Man Who Fell to Earth, where David Bowie’s alien character struggles with human society.

- Fragmented Reality: His work, notably Performance and Bad Timing, delves into the fragmented nature of the psyche and perception, presenting stories in non-linear ways that challenge the viewer’s understanding of time and space.

- Sexuality and Identity: Roeg’s narratives, such as in Don’t Look Now, frequently dissect the complexities of sexual relationships and the fluidity of identity, pushing the boundaries of how sexuality is portrayed on screen.

- Mysticism and Fate: Films like Walkabout and Eureka incorporate elements of mysticism, fate, and destiny, suggesting a world where forces beyond their control or understanding guide characters.

- Cultural and Social Commentary: Across his oeuvre, Roeg uses his characters and settings, whether in the Australian outback or the urban landscapes, to comment on cultural displacement and societal norms.

Styles:

- Non-Linear Narratives: Roeg is renowned for his use of non-linear storytelling, which disorients and re-engages the audience, compelling them to piece together the plot from a mosaic of past, present, and future scenes.

- Striking Visual Imagery: His visual style is marked by bold and often disconcerting imagery, making use of vivid colours and unconventional framing, as evident in the haunting visuals of Don’t Look Now.

- Juxtaposition and Montage: In films like Performance, Roeg employs rapid juxtaposition and montage to create thematic and emotional resonance, often contrasting violence with beauty and chaos with order.

- Use of Music: He integrates music deeply into his films, not just as a score but as a narrative element that complements the visual storytelling, such as the rock soundtrack in Performance.

- Improvisational Performances: Roeg often encouraged improvisation among his actors, resulting in performances that feel spontaneous and unpredictable, contributing to the raw and authentic feel of his characters’ interactions.

Directorial Signature:

- Innovative Editing Techniques: Roeg’s signature can be seen in his revolutionary editing techniques, creating elliptical and sometimes disorienting connections between scenes, which has been influential in cinema.

- Atmospheric Locations: He has a keen eye for choosing locations that enhance the atmospheric tension in his films, making the setting a character in its own right, as the Venice backdrop in Don’t Look Now.

- Intellectual Provocation: Roeg’s films are intellectually provocative, often leaving more questions than answers, pushing audiences to engage with the film beyond the surface narrative.

- Metaphysical Overtones: A Roeg film typically intertwines the narrative with metaphysical overtones, inviting viewers to look beyond the mundane for deeper meanings, as in The Man Who Fell to Earth.

Nicolas Roeg: The 105th Greatest Director