Hiroshi Teshigahara was a prominent Japanese film director and artist best known for avant-garde filmmaking and his collaborations with the writer Kōbō Abe. Their joint ventures often led to thought-provoking and aesthetically striking works. One of Teshigahara’s most well-known films, Woman in the Dunes, received critical acclaim and became a hallmark of 1960s cinema, reflecting his mastery of crafting deeply psychological narratives.

Teshigahara’s filmography is marked by a distinct visual style and recurring themes of identity, existentialism, and the human condition. His use of abstract imagery and emphasis on texture, form, and space provided a tactile dimension to his films, such as The Face of Another. The way Teshigahara combines sound and image is often considered an art form, with a balance that creates a meditative yet unsettling atmosphere. His films consistently challenged traditional storytelling, favouring metaphorical expressions and allegorical narratives, encouraging viewers to engage on a profound intellectual and emotional level.

Teshigahara’s films are both visually innovative and haunting. He often employs unique camera angles, unusual compositions, and meticulous attention to detail, adding complexity to the narrative. His use of natural elements, like sand in Woman in the Dunes, becomes a powerful visual metaphor that extends the story’s themes. His approach towards cinema was innovative and experimental, and he often explored philosophical and societal themes, intertwining them with personal and intimate human experiences.

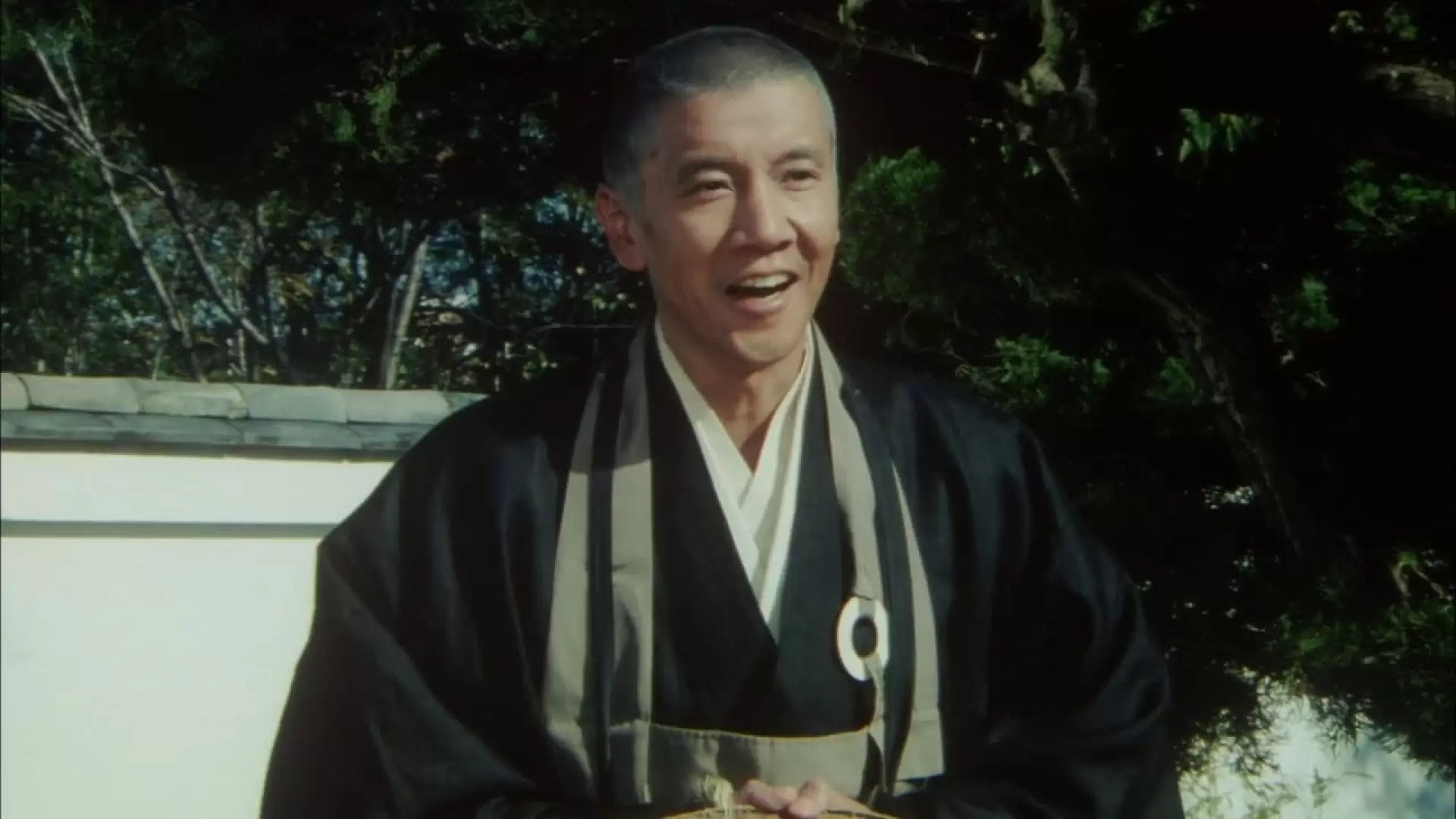

Hiroshi Teshigahara (1927 – 2001)

Calculated Films:

- Woman in the Dunes (1964)

- The Face of Another (1966)

Similar Filmmakers

Hiroshi Teshigahara’s Top 5 Films Ranked

1. Woman in the Dunes (1964)

Genre: Psychological Drama, Psychological Thriller

2. The Face of Another (1966)

Genre: Psychological Drama

3. Pitfall (1962)

Genre: Mystery, Low Fantasy, Crime

4. Antonio Gaudi (1984)

Genre: Art Documentary

5. Rikyu (1989)

Genre: Biographical, Jidaigeki

The Abstract Landscapes of Hiroshi Teshigahara

Born on January 28, 1927, in Tokyo, Hiroshi Teshigahara stemmed from a background steeped in tradition and artistry. He was the eldest son of Sofu Teshigahara, the founder of the avant-garde Ikebana Sogetsu School, which aimed to modernize the ancient Japanese art of flower arrangement. This exposure to artistic abstraction and an early initiation into the interplay of nature and human endeavour would later influence Hiroshi’s filmmaking sensibilities.

Upon completing his formal education in painting and sculpture at the Tokyo National University of Fine Arts and Music in the late 1940s, Hiroshi seemed poised to follow in the familial artistic tradition. However, a trip to Europe during the 1950s broadened his horizons, exposing him to cinema and leading him to the decision to study filmmaking.

Hiroshi’s directorial debut, Pitfall in 1962, was a stark reflection of the complex social environment of post-war Japan. Teaming up with novelist and playwright Kōbō Abe, who penned the screenplay, Teshigahara explored the thematic intersections of identity, class struggles, and the societal costs of rapid modernization. The film, punctuated by elements of surrealism and a quasi-documentary style, spotlighted Teshigahara’s inclination to challenge conventions. While it wasn’t a commercial success, Pitfall helped establish him as a distinctive director and helped set the stage for a slew of avant-garde Japanese films to follow.

During the 1960s, the Japanese film industry experienced a period of tremendous upheaval and change, giving rise to what came to be known as the Japanese New Wave. Like the French Nouvelle Vague, this movement was marked by its defiance of mainstream conventions, a stark focus on contemporary issues, and a willingness to experiment with narrative and form.

Teshigahara, with his fusion of the abstract and the real, emerged as one of the leaders of this movement. However, while his contemporaries like Nagisa Oshima and Shohei Imamura primarily grappled with Japan’s wartime past and changing sexual norms, Teshigahara, influenced by his artistic upbringing, presented an existential exploration of the human condition.

1964’s Woman in the Dunes was the high point of Teshighara’s career and a quintessential Japanese New Wave movie. Reuniting with Kōbō Abe, the film is an allegorical tale of a Tokyo-based entomologist who finds himself trapped in a large sand pit with a mysterious woman. On one level, the film can be interpreted as a commentary on the absurdity of existence and the human tendency to assign purpose where there might be none. On another, it hints at deeper socio-political critiques, particularly the tension between individual desires and societal demands.

Woman in the Dunes received universal acclaim, earning Teshigahara an Academy Award nomination for Best Director, something few non-English language directors have ever achieved. Its haunting visuals—endless stretches of shifting sands, magnified grains of sand resembling barren landscapes—combined with an atmospheric score by Toru Takemitsu ensured the film’s lasting impact.

In 1966, Teshigahara and Kōbō Abe collaborated again, producing The Face of Another. Much in line with their previous efforts, this psychological drama delved into the concept of identity and the human psyche’s fragility. The film tells the story of a man whose face is disfigured in an accident, leading him to don a lifelike mask. While restoring his appearance, this mask also deeply alters his perception of himself and the world around him. With a meticulous blend of surreal visuals and a potent narrative, Teshigahara further cemented his reputation as a director who navigates the intricacies of human emotions and existential dilemmas.

Post the 1960s, Teshigahara’s cinematic output diminished, with only a handful of films in the subsequent decades. Though crafted with his characteristic finesse, these films, including The Man Without a Map and Rikyu, lacked the avant-garde energy of his early works. Rikyu, focusing on the life of the 16th-century tea master Sen no Rikyu, reflected a more contemplative and historically conscious Teshigahara. While these films had their merits, and Rikyu especially was visually beautiful, they didn’t quite work as well as his 60s masterpieces.

By the 1970s, Teshigahara began to shift his focus from cinema to the Sogetsu School of Ikebana, following his father’s footsteps. Teshigahara’s involvement in Sogetsu, which sought to modernize and globalize traditional Japanese floral art, echoed his cinematic efforts: challenging conventions, bridging the old with the new, and finding beauty in abstraction. In this period, Teshigahara produced several documentaries that portrayed the world of Ikebana and the artistry of the Sogetsu School.

Despite a relatively limited filmography, his impact is profound, especially regarding the Japanese New Wave. His collaborations with Kōbō Abe produced some of the most innovative and thought-provoking films of the 20th century. Teshigahara’s films, with their nuanced narratives, ethereal visuals, and potent allegories, continue to be subjects of study and admiration.

Most Underrated Film

Pitfall, Hiroshi Teshigahara’s directorial debut, has long remained in the shadows of his more celebrated works like Woman in the Dunes and The Face of Another. But a closer look reveals a film teeming with brilliance and a harbinger of the director’s impending cinematic prowess.

Common criticisms levelled against the film revolve around its pacing and seemingly disjointed narrative. The story pivots around a man mistaken for someone else and killed, only to become a spectre observing the consequences of his own death. Its dreamlike sequences, punctuated by stark realities, left several viewers grappling for a linear storyline.

However, this is precisely where the film’s charm lies. One of the standout scenes involves the protagonist witnessing his own life from the afterlife, a haunting portrayal that pushes boundaries in storytelling and cinematographic techniques. The juxtaposition of the ethereal with the tangible, the living with the dead, presents a poignant reflection on existence, identity, and the transient nature of life.

Hiroshi Teshigahara: Themes and Style

Themes:

- Existential Exploration: Teshigahara frequently delved into profound existential questions about human nature, existence, and purpose. Films like Woman in the Dunes and The Face of Another exemplify this, confronting audiences with the inherent absurdities and dilemmas of life.

- Identity and Alienation: The struggle for self-definition and the feeling of being ‘othered’ recur in his works. The Face of Another is a prime example, where physical disfigurement leads to introspection and societal estrangement.

- Societal Conformity vs. Individual Desires: Teshigahara’s characters often grapple with societal pressures and their personal aspirations, reflecting post-war Japan’s changing dynamics.

- Nature and Humanity: Growing up in the world of Ikebana, Teshigahara often juxtaposed nature’s raw power and beauty against human endeavours, highlighting both conflict and coexistence.

Styles:

- Surrealism: Teshigahara frequently blended the dreamlike with the tangible. This can be seen in the ghostly narratives of Pitfall or the confounding sandscapes of Woman in the Dunes.

- Innovative Cinematography: His films are renowned for their visual splendour, using unique camera angles, close-ups, and an emphasis on texture to draw viewers into the story’s emotional core.

- Collaboration with Kōbō Abe: Teshigahara’s films took on a distinctive narrative depth and complexity when paired with Abe’s screenplays, creating a potent blend of philosophical musings and visual storytelling.

Directorial Signature

- Visual Abstraction: Perhaps influenced by his exposure to the Ikebana Sogetsu School, Teshigahara had a penchant for capturing the abstract within the mundane. Whether it was the magnified grains of sand in Woman in the Dunes or the distorted reflections in The Face of Another, he brought a unique visual language to cinema.

- Atmospheric Soundscapes: Teshigahara often collaborated with composer Toru Takemitsu to create ambient, haunting scores that elevated the mood and themes of his films.

- Meticulous Framing: Every shot in a Teshigahara film feels deliberate, capturing both the grandeur and minutiae of his settings. The endless dunes or the claustrophobic interiors in his films are more than just backdrops; they are vital narrative elements.

- Narrative Depth: Beyond the visual, Teshigahara’s films are characterized by their layered storytelling. They demand introspection, urging viewers to confront and question their understanding of society, identity, and existence.

Further Reading:

Articles and Essays:

- Teshigahara, Hiroshi by Dan Harper, Senses of Cinema

- Hiroshi Teshigahara’s Multimedia Tradition by Rachel Carvosso, Tokyo Art Beat

- The Face of Another: Double Vision by James Quandt, Criterion

- How Tōru Takemitsu and Hiroshi Teshigahara Explored Japan’s Postwar Psyche by Lena Lie, Red Bull Music Academy

- A Sisyphus in the Sand by David Mermelstein, The Wall Street Journal

Hiroshi Teshigahara – The 275th Greatest Director