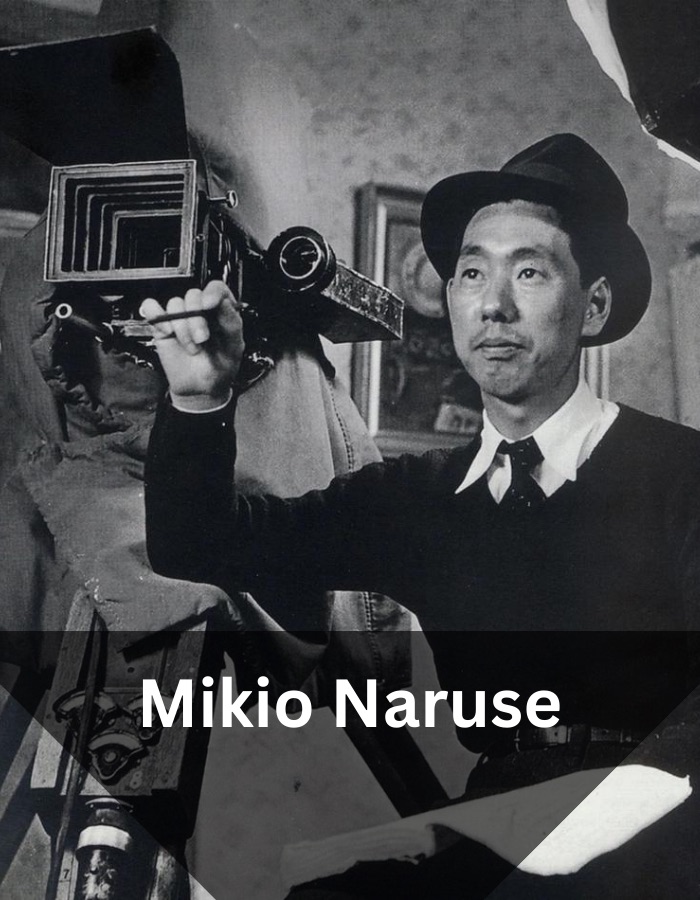

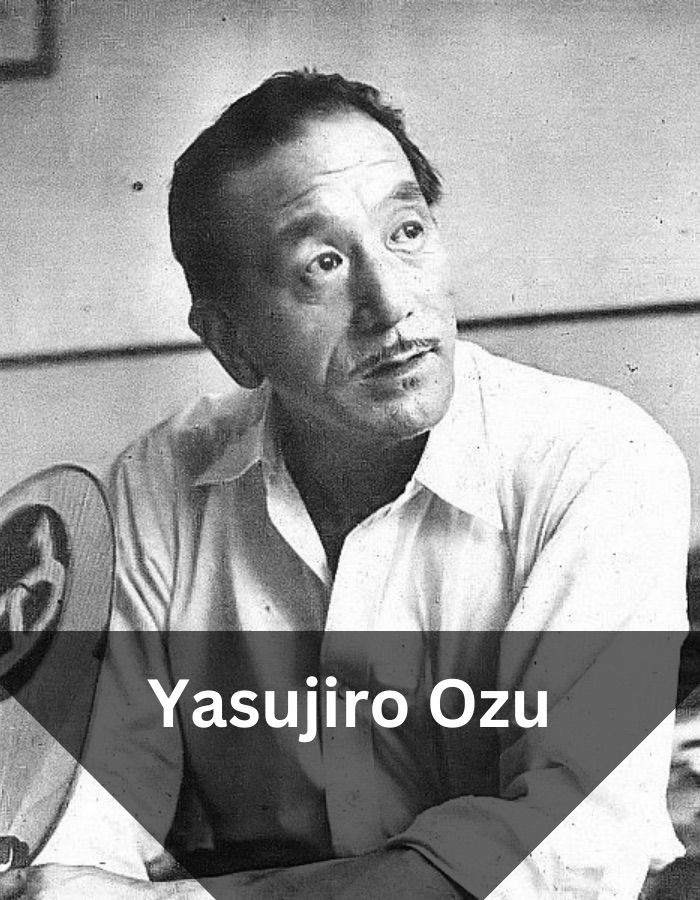

Below are some of the best Japanese directors ever. Click on their pictures to discover more about them.

A Brief History of Japanese Pre-War Cinema

Japanese cinema in the 1930s, while inheriting the artistic legacy of pioneers such as Shozo Makino, experienced a period of significant transformation and growth. The decade began with the transition from silent films to talkies, a change that Japanese filmmakers embraced with enthusiasm, integrating the country’s rich oral traditions into their narratives. Directors like Yasujiro Ozu began experimenting with the possibilities of sound, developing a minimalist style that reflected the nuances of everyday life. Ozu’s early thirties works like “I Was Born, But…” conveyed subtle social critiques through the lens of family and generational conflict. Meanwhile, filmmakers like Hiroshi Shimizu explored the mobility of the camera to capture the nation’s changing social landscape.

The industry saw a rise in the popularity of genres such as the jidaigeki and the shomingeki, the latter of which portrayed the lives of ordinary people and was perfected by directors like Ozu and Mikio Naruse. Naruse’s films in the 1930s, including “Wife! Be Like a Rose!”, often centred on strong female characters navigating societal expectations, a theme that resonated with the contemporary audience. Kenji Mizoguchi, another prominent figure, began to gain recognition for his meticulous compositions and one-scene-one-shot approach, which would later become his signature. His works from this era, such as “The Story of the Last Chrysanthemums”, showcased his burgeoning talent and thematic concern with the plight of women.

As the decade progressed, the impending war began to cast a shadow over the film industry. In the late 1930s, the government’s increasing control over cinematic content led to the production of films that echoed nationalistic and militaristic sentiments. Directors were often conscripted into the war effort, either through creating works that aligned with the state’s ideology or by being sent to the front lines to document Japan’s military campaigns. This conscription not only interrupted the careers of many filmmakers but also steered the trajectory of Japanese cinema into an era where the creative freedom once enjoyed by the likes of Makino, Ozu, and Mizoguchi was significantly curtailed.