Akira Kurosawa is a Japanese filmmaker known for his narrative style, characters’ depth, and innovative cinematic techniques. His films, particularly those in the samurai genre, have left an indelible mark on international cinema. Kurosawa’s portfolio includes masterpieces like Seven Samurai, Rashomon, and Ran. These films showcase his flair for epic storytelling, complex characters, and unique ability to weave diverse narrative threads together.

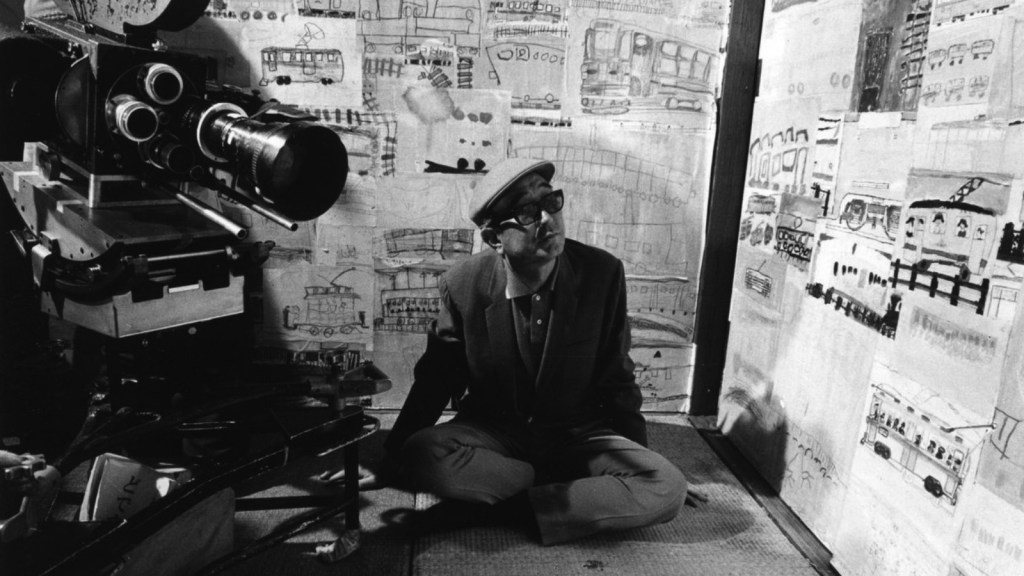

Raised in a family with samurai ancestry, Kurosawa developed a keen interest in art, literature, and film from an early age. Initially aspiring to be a painter, his artistic talents later significantly influenced his cinematic vision. After a brief stint in the Japanese film studio system as an assistant director, he made his directorial debut in 1943 with Sanshiro Sugata. His early films were produced during a turbulent time in Japan’s history, marked by the Second World War and its aftermath, events that significantly influenced his work.

Kurosawa’s films often centred around themes of social justice, existentialism, and humanism, tackling profound issues of morality and ethics. In Rashomon, he ingeniously used multiple perspectives to narrate a single event, a narrative device now known as the “Rashomon effect“. Seven Samurai and Yojimbo exemplify his social consciousness, highlighting the plight of the marginalised and showcasing the samurai as a symbol of moral duty and honour. His later films, including Ran and Kagemusha, feature powerful explorations of Shakespearean themes of power, betrayal, and human folly, presenting a deeply introspective view of humanity.

Kurosawa’s visual style was marked by dynamic framing, deep focus, and innovative editing techniques. His meticulous attention to detail and his remarkable ability to create visually stunning compositions were evident in his use of weather elements and his dramatic use of movement within scenes. For instance, the epic battle sequences in Seven Samurai and Kagemusha showcase his mastery of creating visually arresting cinema, blending intense action with stunning cinematography.

Kurosawa’s influence extends far beyond Japan, shaping the work of many Western directors. His films have been remade, reimagined, and referenced by many filmmakers, including George Lucas, Steven Spielberg, and Martin Scorsese. His influence is perhaps most apparent in epic cinema and the modern action genre. Kurosawa’s storytelling and visual techniques influenced films like Star Wars and The Magnificent Seven.

Akira Kurosawa (1910 – 1998)

What Impacted His Placement:

- One Wonderful Sunday (1947)

- Drunken Angel (1948)

- Stray Dog (1949)

- Rashomon (1950)

- Ikiru (1952)

- Seven Samurai (1954)

- Throne of Blood (1957)

- The Hidden Fortress (1958)

- The Bad Sleep Well (1960)

- Yojimbo (1961)

- Sanjuro (1962)

- High and Low (1963)

- Red Beard (1965)

- Dodes’ka-den (1970)

- Dersu Uzala (1975)

- Kagemusha (1980)

- Ran (1985)

- Dreams (1990)

Similar Filmmakers

Akira Kurosawa’s Top 10 Films Ranked

1. Seven Samurai (1954)

Genre: Jidaigeki, Chambara, Epic

2. Ran (1985)

Genre: Jidaigeki, Tragedy, War, Epic

3. Ikiru (1952)

Genre: Drama, Melodrama

4. Rashomon (1950)

Genre: Jidaigeki, Mystery, Crime

5. High and Low (1963)

Genre: Crime, Drama, Police Procedural, Neo-Noir

6. Yojimbo (1961)

Genre: Chambara, Jidaigeki

7. Red Beard (1965)

Genre: Jidaigeki

8. Dersu Uzala (1975)

Genre: Adventure, Biographical, Drama

9. Throne of Blood (1957)

Genre: Jidaigeki, Tragedy, War, Low Fantasy

10. Kagemusha (1980)

Genre: Jidaigeki, War, Epic

Akira Kurosawa: From Rashmon to Ran

Born on March 23, 1910, in Tokyo’s Ōmori district, Kurosawa was a young man infused with creativity, his paintings radiant with a mysterious quality that hinted at an otherworldly talent. Yet it was in the dark chambers of Japanese cinema where Kurosawa’s talents would ultimately ignite, a place where he would craft worlds, not merely on canvas but in the very fabric of emotion and existence. His early years were marked by a rigorous apprenticeship under directors like Kajiro Yamamoto, a time that sharpened his senses and honed his inherent understanding of the human psyche.

The flames of World War II were still smouldering when Kurosawa made his directorial debut with Sanshiro Sugata in 1943; not the best debut ever, but a competent film that hinted at the complexities of its director.

Towards the end of the 40s, Kurosawa started to come into himself with films like Drunken Angel and Stray Dog, painting portraits of post-war Japan that were bleak yet strangely beautiful. He showed his capacity to show despair, yet within the gloom, there glimmered sparks of redemption and resilience. His protagonists were flawed, yes, but also capable of profound transformation.

The international spotlight found Kurosawa with Rashomon, a film that did not just break cinematic conventions; it shattered them. Here was storytelling at its most innovative, a narrative splintered into conflicting truths and moral ambiguity. Kurosawa was no longer just a director; he was an iconoclast.

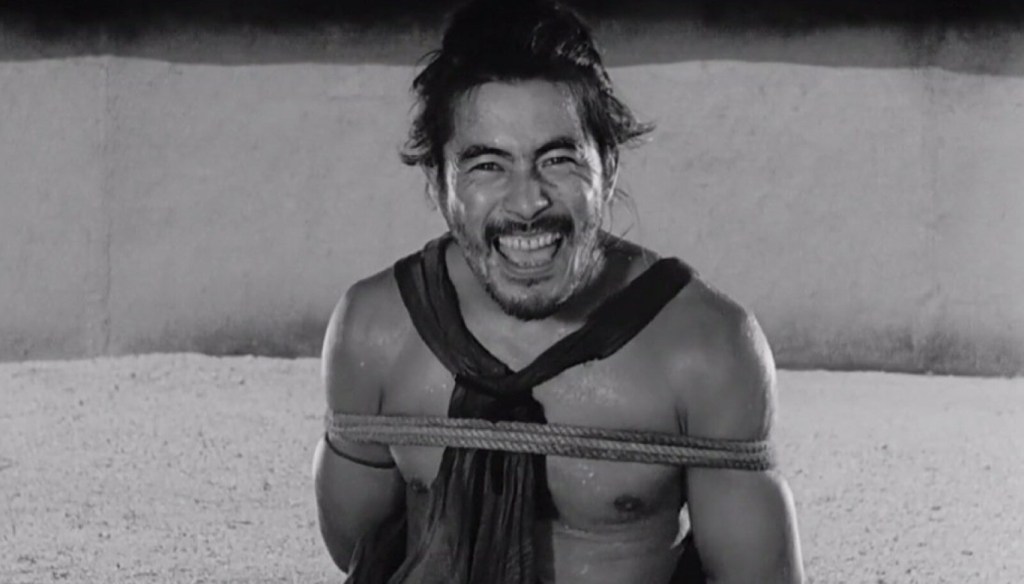

The following years were a storm of creativity for Kurosawa. Ikiru, with its existential wanderings, and Seven Samurai, a masterwork that transformed the landscape of cinema, were not just films; they were epics of the human soul. Kurosawa was digging deep, excavating the very essence of humanity and laying it bare for the world to see.

But it wasn’t all praise and adoration. Kurosawa’s relentless pursuit of perfection and refusal to bend to commercial whims made him a difficult figure in the Japanese film industry.

With Throne of Blood, Kurosawa ventured into the haunting landscape of Shakespeare’s “Macbeth,” transposing it to feudal Japan. The film was dense with atmospheric dread, a psychological battlefield where ambition, honour, and madness danced in a grim ballet. Kurosawa’s adaptation was no mere retelling; it was a reinterpretation, a work of art that infused a classic tale with a uniquely Japanese soul.

The late 1950s and 1960s marked a period of expansion and exploration for Akira Kurosawa, not just within the boundaries of his homeland but beyond, across oceans and cultures. Hidden Fortress was a symphony of adventure, a tale of loyalty and betrayal transcending geographical barriers. Its influence was palpable, resonating even in the distant corridors of Hollywood, inspiring the likes of George Lucas and his galaxy far away.

But fame and recognition did not lead Kurosawa to tread a path of ease or conformity. His next ventures, The Bad Sleep Well, Yojimbo and Sanjuro, were rebellious and audacious. Here was a director refusing to be confined, critiquing corporate corruption, challenging the samurai ethos, and constructing narratives that were a jab at the establishment.

High and Low saw Kurosawa delving into the gritty realism of urban life, crafting a thriller as tense as it was thought-provoking. It was a reflection of class and morality, a mirror held up to society’s face. Red Beard took this introspection deeper, weaving a tale of compassion, humanity, and the delicate balance between power and humility.

As the Japanese New Wave surged, Kurosawa found himself at odds with this emerging movement. He was a maestro of the old guard, yet his artistry was anything but stagnant. The new generation’s radicalism and abandonment of classic storytelling set him adrift in Japanese cinema long after the other traditional masters, Ozu, Mizoguchi and Naruse, had passed.

Dodes’ka-den marked a significant departure, an experimental endeavour that mirrored the director’s inner turmoil. It was Kurosawa not just responding to the New Wave but absorbing, challenging, and redefining it. The film’s critical and commercial failure was a blow, yet it proved Kurosawa was still genuine and untainted by commerciality.

The international acclaim and the adoration did not shield Kurosawa from the struggles that marked the industry. There were battles with studios, skirmishes with censors, and the ever-looming shadow of financial constraints. These led to fewer opportunities for the old master, who had to seek further, more accommodating shores for his ventures.

Resulting in the USSR-produced Dersu Uzala in 1975, which reflected Kurosawa’s global appeal and willingness to venture into the unknown. It was a tale of friendship and survival, a narrative as expansive as the Siberian landscapes it depicted. The film was his only non-Japanese language movie and was a colossal success, winning the Best Foreign Language Film at the 49th Academy Awards. Perhaps this would be his swan song, a final round of applause for a master whose proteges were only just emerging.

But, the journey of Akira Kurosawa was not yet complete. The twilight years of Akira Kurosawa’s career were anything but a gentle fade. They were a blaze of creativity, a reaffirmation of a vision that had never ceased to challenge, innovate, and inspire.

Kagemusha was a canvas as broad and intricate as any Kurosawa had painted before. It was a tale of duality, of deception, of the thin line that separates the ruler from the ruled. It was Kurosawa at his most operatic, his artistry undimmed, his touch as sure as ever.

But Ran truly signalled Kurosawa’s enduring brilliance. Here was a film that was a spectacle, meditation, visual feast, and existential quest. Adapting Shakespeare’s “King Lear” to the milieu of feudal Japan, Kurosawa crafted a tragedy that was as timeless as it was specific.

One sequence in particular, the storming of the Third Castle, is a masterclass in filmmaking. The scene unfolds with a haunting silence, devoid of music or dialogue, as the chaos of battle rages. It’s a symphony of visual poetry, a dance of death and destruction that’s at once beautiful and harrowing. The imagery – a mixture of vibrant colour and stark desolation – encapsulates the very essence of warfare, a madness both alluring and horrifying.

Dreams took Kurosawa’s art into the surreal, a series of vignettes that reflected the director’s imaginings and fears. It was Kurosawa not just telling stories but sharing his soul, his worries for humanity, and his longing for harmony.

Rhapsody in August and Madadayo were softer, more reflective pieces, the works of a man looking back and looking inward. They were poignant, personal, filled with the wisdom of age and the tenderness of retrospection.

Kurosawa’s final years were marked by a serene determination, a graceful acceptance of the passing of time, yet devoid of any diminishment in passion or creativity. The master was still at work, his hand steady, his eye clear.

It’s not hard to love Akira Kurosawa’s films. One of the reasons he never quite managed to thrive in Japan was because, according to contemporary sources, his works were seen as too Western. It is perhaps ironic then that this sensibility enabled him to reach global audiences and become celebrated as one of the 20th century’s greatest directors.

Most Underrated Film

Kagemusha, a historical epic released in 1980, often finds itself overshadowed by the grandeur of other works in Akira Kurosawa’s oeuvre, especially the magnum opus Ran. Both films share thematic territory, dealing with political intrigue, betrayal, and human folly in the context of feudal Japan.

One scene encapsulates the film’s essence is when the titular Kagemusha, a common thief impersonating a warlord, stands on a balcony overlooking the troops. He is both an imposter and a symbol, embodying a stark contradiction. As he raises his hand to shield his eyes from the sun, the troops mirror his action in obedience, highlighting the power of perception and how it intertwines with reality. The moment is sublime, a quiet commentary on leadership, identity, and the fragile nature of power.

Comparatively, Ran thrives on grander theatricality and is rooted in Shakespearean drama, whereas Kagemusha offers a more nuanced, introspective exploration.

Compared to the visceral emotional impact of Dersu Uzala or the artistic audacity of Ran, Kagemusha may seem restrained or even aloof to some viewers. Critics have pointed to its slower pacing and the less empathetic central character as factors that might distance the audience.

However, these aspects that may detract for some make Kagemusha a masterpiece in its own right. It is a film that does not seek to please or to conform but to probe, question, and illuminate. It’s a work of profound intellectual and aesthetic value, rich in symbolism and artistry, deserving of deeper exploration and acclaim.

Akira Kurosawa: Themes & Style

Themes:

- Human Nature and Morality: Kurosawa’s films often explore the complex nature of humanity, morality, and ethics. From the duality of human character in Rashomon to the existential questions in Ikiru, he delved into the human soul’s intricacies.

- Social Critique and Political Commentary: Many of his films serve as commentaries on social issues, political systems, and historical events. Works like The Bad Sleep Well and High and Low criticise corruption and the socio-economic divide.

- War and Honor: Themes of war, honour, and code of conduct are prevalent in films like Seven Samurai, Throne of Blood, and Kagemusha. These films portray not just physical conflict but the internal struggle within characters.

- Redemption and Transformation: Themes of redemption and personal growth play vital roles in films like Red Beard and Dodes’ka-den.

Styles:

- Visual Storytelling: Kurosawa’s visual composition was always striking, using framing, colour, and movement to convey mood and meaning.

- Narrative Structure: He was known for his innovative use of narrative techniques, employing flashbacks, multiple perspectives, and nonlinear storytelling, most famously in Rashomon.

- Use of Weather Elements: Kurosawa frequently used weather elements as metaphors or to enhance the story’s atmosphere. The rain in Rashomon and the wind in Yojimbo are iconic examples.

- Collaboration with Actors: His collaboration with actors like Toshiro Mifune brought intensity and depth to the characters that became integral to his films’ success.

Directorial Signature:

- Epic Scale: Kurosawa’s works often encompass an epic scale, whether in the broad sweep of history, as in Ran, or the depth of human emotion, as in Ikiru.

- Artistic Precision: Every frame in a Kurosawa film feels carefully composed, reflecting a painterly attention to detail.

- Emotional Depth: Kurosawa’s films resonate emotionally, often leaving a lasting impact on viewers through their profound engagement with human feelings and dilemmas.

- Genre Versatility: From samurai epics to modern dramas, Kurosawa’s versatility across genres is noteworthy. He transcended genre boundaries, infusing each film with his unique vision.

Further Reading

Books:

- The Warrior’s Camera: The Cinema of Akira Kurosawa by Stephen Prince – A comprehensive study of Kurosawa’s career.

- Akira Kurosawa: Master of Cinema by Peter Cowie – A visually rich examination of Kurosawa’s work.

- Something Like an Autobiography by Akira Kurosawa – Kurosawa’s own account of his life and career.

- Kurosawa: Film Studies and Japanese Cinema by Mitsuhiro Yoshimoto – An academic exploration of Kurosawa’s films and their place within Japanese cinema.

Articles and Essays:

- Kurosawa Akira: Films of Love and Justice by Tsuzuki Masaaki, nippon.com

- Kurosawa, Akira by Dan Harper, Senses of Cinema

- Akira Kurosawa’s Dreams: Quiet Devastation by Bilge Ebiri, Criterion

- Remembering Kurosawa by Donald Ritchie, Criterion

- KUROSAWA ON HIS INNOVATIVE CINEMA by Audie Bock, The New York Times

Documentaries:

- Kurosawa’s Way (2011), directed by Catherine Cadou – A documentary where various filmmakers share how Kurosawa influenced them.

- A.K. (1985), directed by Chris Marker – A documentary on the making of Ran, provides insight into Kurosawa’s process.

Akira Kurosawa: The 3rd Greatest Director