René Clair was a pioneering French director whose influence spans multiple decades and film movements yet remains a somewhat under-appreciated figure. Despite having enjoyed a prestigious position in the global film industry, particularly during the silent era and early sound films, his contributions are often overlooked.

Some of his films may feel dated to the contemporary viewer. Still, the essence of Clair‘s filmmaking – his commitment to innovative storytelling, his embrace of new technologies, and his ability to infuse charm and wit into a wide range of narratives – remains timeless.

Clair believed in the transformative power of cinema, and this belief shines through in his body of work. Understanding Clair’s directorial style and legacy is a journey through his passion, creativity, and remarkable influence on cinematic storytelling.

Lightness and Wit

René Clair’s cinematic universe is a delightful fusion of lightness and wit, a testament to his extraordinary prowess in crafting stories that have an enduring charm. His films, renowned for their delightful humour and vivacious storytelling, are reflections of his natural penchant for comedy and satire.

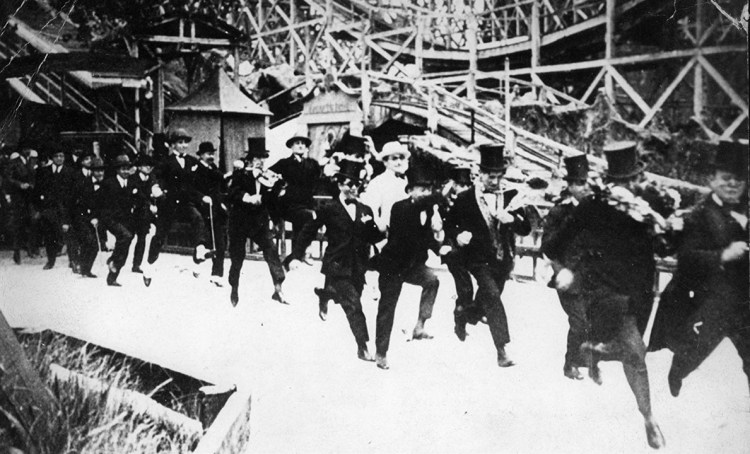

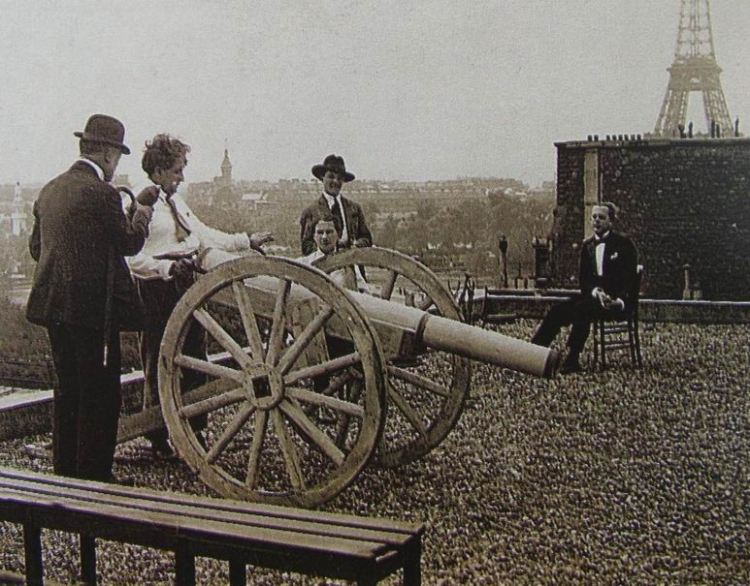

One can trace this signature style to his silent film era, a case in point being Paris Qui Dort, where Clair ingeniously deploys humour, turning the City of Light into a surreal dreamscape frozen in time, thereby allowing his characters to amuse themselves with the deserted city’s spoils. Another silent film, Entr’acte, created in collaboration with artists from the Dada movement, is filled with absurd and whimsical scenarios – a peculiar funeral procession, an ostrich-led chariot, and a balletic cannon shoot-out – which reflect Clair’s sophisticated wit.

Even when Clair moved to sound films, he didn’t abandon his knack for light-hearted storytelling. His films of the 1930s, such as Le Million and Under The Roofs of Paris, continued to infuse comedy into narratives of everyday life in Paris. These films, steeped in the tradition of operetta, deploy humour through playful scenarios and sharp dialogues, serving up comedy in bite-sized vignettes that effortlessly lighten the mood.

Clair’s wit morphed into a unique form of cinematic satire in his later works. Films like I Married a Witch and Beauty of the Devil use supernatural themes as allegorical devices, sprinkling humour throughout their narratives to dissect human foibles and societal conventions. The witchcraft in I Married a Witch becomes a comedic tool that Clair uses to explore gender dynamics. In Beauty of the Devil, Clair uses Faust’s classic tale to satirically critique the obsession with youth and power.

Clair’s 1950s films, such as Gates of Paris and Beauties of the Night, while seemingly lighter on the surface, are filled with sharp satire. They offer a critical view of society but wrap it in such a jovial guise that the critique is as enjoyable as it is thought-provoking.

No discussion of Clair’s wit can be complete without mentioning films like Freedom for Us and Man About Town, where comedy forms the bedrock of the narratives. In Freedom for Us, a story of two escaping convicts, the characters’ misadventures creates an environment rife with hilarity. Similarly, Man About Town serves as a playful critique of the film industry itself.

Even in his adaptations of existing works, Clair’s sense of humour and lightness persist. His rendition of Agatha Christie’s And Then There Were None, and the adaptation of Labiche’s play in Two Timid Souls carry his signature comedic touch, reiterating his ability to inject his unique brand of wit into any narrative.

Thus, Clair’s body of work, brimming with lightness and wit, showcases his ability to blend comedy and satire effortlessly into his narratives. His films are a joyous celebration of life’s absurdities, served with a side of insightful critique. René Clair’s ability to create such engaging, humorous narratives is a testament to his genius as a storyteller and a key aspect of his distinctive directorial style.

Surrealist Influences

In the early stages of his career, René Clair was significantly influenced by the Surrealist movement, an association that deeply imprinted on his films and, consequently, his directorial style. This surrealistic underpinning set his work apart, enabling him to construct a unique cinematic language that amalgamated the ordinary with the extraordinary.

His silent film Entr’acte is a veritable compendium of surrealistic elements. Its non-linear narrative, an orchestra of eccentric scenes, and a penchant for visual illusions effectively disorient conventional storytelling norms. This was a bold experiment for the time and marked Clair’s early foray into surrealist cinema.

Paris Qui Dort similarly incorporates surrealism, using the theme of a frozen Paris to create a dreamlike ambience. The city, devoid of its bustling life, becomes an uncanny playground for the film’s characters, injecting a profound sense of the surreal into the otherwise ordinary urban landscape.

The influence of surrealism didn’t end with his silent films. As Clair moved into sound films, surreal elements continued to pervade his work. For instance, in I Married a Witch, the introduction of the supernatural – the reincarnated witch who seeks revenge – disrupts the normative reality, lending a surreal tone to the film. Similarly, in Beauty of the Devil, Clair employs surreal elements to blur the line between reality and illusion, effectively enhancing the narrative’s philosophical undertones.

René Clair’s embrace of surrealism gave his films a distinctive edge. Whether through dreamlike sequences, visual illusions, or unorthodox narrative structures, he ingeniously blurred the boundaries between the real and the fantastical, establishing himself as a pioneering figure in surrealist cinema.

Poetic Realism

René Clair’s contributions to the poetic realism movement significantly shaped his filmmaking style. Known for weaving everyday life’s nuances with a poetic brush, his films are delightful illustrations of ordinary moments transformed into extraordinary cinematic experiences.

One of Clair’s notable films embracing poetic realism is Under The Roofs of Paris. Set in the quintessential milieu of Paris, the film adeptly captures the city’s charm, love, and struggles with a delicate, poetic touch. The film encapsulates the essence of Parisian life – a romantic yet realistic portrait of common people living their ordinary lives, elevating the mundane.

Le Million, another classic example, imbues a simple tale of a lottery ticket hunt with poetic grandeur. The film presents a whimsical journey through the backstreets of Paris, turning an ordinary narrative into an enchanting poetic spectacle.

Similarly, Freedom for Us takes a common storyline of two escaped convicts and adds layers of poetic depth. The film seamlessly navigates between reality and dream-like sequences, subtly invoking the poetic realism that defines Clair’s unique storytelling style.

Visual Innovation

René Clair’s legacy in film is marked not just by his narrative prowess but also by his relentless visual experimentation. His innovative use of visual techniques was ahead of his time, rendering his films visually dynamic and aesthetically distinctive.

In his early film, Entr’acte, Clair demonstrated remarkable innovation by using techniques like slow-motion and stop-motion animation. The film’s visual style is a medley of unconventional camera angles, double exposure, and innovative editing – creating a unique, disjointed rhythm that challenges the viewer’s perception.

In Paris Qui Dort, Clair used pioneering special effects to depict a Paris frozen in time. The creative use of aerial shots of the empty city provided a visually stunning and surreal landscape that became the film’s central spectacle.

Clair’s innovation was not limited to silent films. In sound films like Beauty of the Devil, he used visual effects to depict the transference of youth and age between two characters. Similarly, in And Then There Were None, his ingenious camera work created suspense and intrigue in this gripping adaptation of Agatha Christie’s novel.

Emphasis on Music and Sound

René Clair understood the emotional potential of music, using it not merely as a background element but as a narrative device to enhance the mood, rhythm, and storytelling.

In Under The Roofs of Paris, one of his first sound films, Clair made remarkable use of song and ambient sounds. The recurring theme song acts as a narrative thread, tying together the lives of the characters, while the sound of rain, chatter, and footsteps brings the Parisian setting to life.

Similarly, in Le Million, music is the film’s backbone, reflecting the operetta style. Here, the music carries the story forward, with characters breaking into song, using music as a mode of expression.

Clair’s long-time collaboration with composer Georges Auric, starting with Beauty of the Devil, resulted in some of the most memorable and evocative film scores. The enchanting music in Beauties of the Night and Gates of Paris is a testament to their fruitful partnership.

Social Commentary

Despite his light-hearted tone, Clair’s films often incorporated subtle social commentary, offering insights into the complexities of society. His satirical approach often highlighted societal norms, class distinctions, and the human condition.

Freedom for Us, for example, uses humour to critique the harsh conditions of the working class. Through the escapades of two convicts, the film reflects on the paradox of freedom in a class-structured society.

In I Married a Witch, Clair uses the theme of witchcraft to explore gender dynamics and societal expectations of women. The film subtly scrutinises the stereotypes associated with women through a comedic lens.

While comedic in nature, Gates of Paris and Man About Town offer critical views of society. In Gates of Paris, Clair paints a vivid picture of the Parisian slums, highlighting the disparity between social classes. In Man About Town, he provides a playful critique of the film industry, subtly commenting on its glamour and artifice.

René Clair’s ability to weave insightful societal critiques into light-hearted narratives underscores his distinct directorial style and perceptive understanding of societal dynamics.

Humanism and Optimism

René Clair’s ‘cinematic universe’ is filled with a palpable sense of humanism and optimism. Despite his characters’ complexities and challenges, they invariably exude a positive outlook on life and a tenacious spirit.

In Two Timid Souls, the two bashful protagonists overcome their inhibitions to stand up to bullies. With its heartwarming resolution, this story showcases Clair’s belief in the inherent goodness of people and their ability to confront their fears.

Similarly, in July 14, a film set against the backdrop of political upheaval, Clair infuses his characters with resilience and hope. Despite the tumultuous circumstances, they find solace in their human connections, embodying the film’s undercurrent of optimism.

Even in And Then There Were None, based on Agatha Christie’s grim murder mystery, Clair manages to instil a sense of optimism. Despite their dire situation, the survivors never lose their hope for survival, embodying Clair’s humanist ethos.

Why Isn’t Rene Clair Well Known?

René Clair’s works, characterised by their wit, humanism, and visual experimentation, profoundly impacted his contemporaries, influencing the likes of Charlie Chaplin and, subsequently, the cinematic landscape itself.

Despite his profound influence and recognition during his active years, his place in the canon has since been debated. Where many French directors of the 1920s and 30s were elevated and reappraised by the critics of the French New Wave, Clair was, instead, dismissed by the Cahier du Cinema critics. This lack of recognition has contributed to Clair’s relatively subdued presence in modern film discourse.

Furthermore, despite his films’ timeless themes and techniques, Clair’s work has not always found resonance with contemporary audiences, often labelled as dated or out of touch with current sensibilities. The distinct charm and wit that characterised his narratives can feel unfamiliar, even alien, in the context of modern cinema, which has often moved towards darker, more explicit storytelling.

Yet, this perceived obscurity does not diminish the significance of Clair’s work. His innovations, particularly in sound, visual techniques, and narrative structures, remain relevant. His narratives, imbued with humanism and optimism, still find echoes in films championing the human spirit.

Moreover, in an era of cinematic revisitation and re-evaluations, Clair’s work stands poised for rediscovery. His body of work, with its blend of surrealism, poetic realism, and societal commentary, can offer a fresh perspective and a source of inspiration for contemporary filmmakers and audiences.