Zhang Shichuan was a Chinese director often considered the father of Chinese cinema. Best known for his formative contributions to the silent film era in China, his films are often recognised for their intricate storytelling, utilisation of traditional themes, and their portrayal of the socio-cultural dynamics of the time.

Beginning his career in the 1910s, Zhang Shichuan directed some of the earliest films in Chinese history, laying the groundwork for the industry’s future. Collaborating with Zheng Zhengqiu, he founded the Mingxing Film Company, which became the first major film studio in China. His films frequently delved into societal issues, including family dynamics, the consequences of modernisation, and the clash between traditional values and emerging Western influences. For instance, in his acclaimed work The Difficult Couple, Zhang explored the intricacies of marital relationships against the backdrop of a rapidly changing society.

His approach to filmmaking often merged stage conventions from traditional Chinese theatre with emerging cinematic techniques. This blending not only showcased his unique directorial style but also rendered a visual language that resonated deeply with his audience. His films often incorporated symbolic elements, such as traditional costumes and architecture, to further accentuate the cultural context. Tragically, despite his pivotal role in shaping the early Chinese cinematic landscape, Zhang Shichuan has been largely forgotten, with much of his work lost to time. Yet, in terms of significance, Zhang is to Chinese cinema what D.W. Griffith is to Western cinema: a foundational figure whose innovations and narratives set the tone for the generations that followed.

Zhang Shichuan (1890 – 1954)

Calculated Films:

- NA

Similar Filmmakers

- Bu Wancang

- Cheng Bugao

- Fei Mu

- Hou Yao

- Liu Na’ou

- Ma-Xu Weibang

- Ren Pengnian

- Sadao Yamanaka

- Shen Fu

- Shi Dongshan

- Shozo Makino

- Sun Yu

- Wu Yonggang

- Xie Jin

- Yasujiro Shimazu

- Yuan Muzhi

- Zhang Huichong

- Zheng Zhengqiu

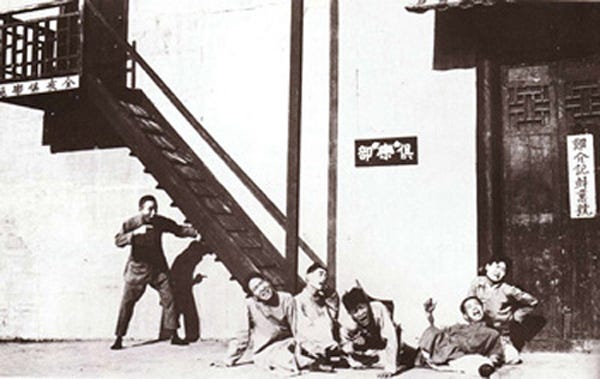

Zhang Shichuan and Zheng Zhengqiu

Griffith, Melies, Guy-Blache… Shichuan and Zhengqiu? They might not be canonised names, but if you ever loved the films of Zhang Yimou, you should know that it all starts with them.

Zhang Shichuan and Zheng Zhengqiu were not the first to introduce the magic of cinema to China. That honour goes to Westerners and Ren Qingtai, who had already dabbled in the art form but with little success. What set Zhang and Zheng apart was their collaboration and unique points of view.

But who were these men, and how did their paths converge? Zhang’s journey began in Ningbo, where tragedy struck early with the death of his father. This led him to Shanghai, where he worked under the guidance of his uncle, an agent. Zheng, on the other hand, was an aristocrat, deeply entrenched in the Shanghai theatre scene, with a particular fondness for Peking Opera and modern plays. Their backgrounds were as contrasting as night and day: Zhang, the pragmatic businessman, and Zheng, the passionate artist.

Their collaboration began almost serendipitously. Zhang, who initially had little interest in films, was roped into the American-owned Asia Film Company. When the company expressed interest in adapting a popular Shanghai play, Zhang reached out to Zheng, marking the beginning of a partnership that would change Chinese cinema forever. Their first joint venture, “The Difficult Couple,” hinted at their compatibility: Zhang directed, while Zheng penned the script. The film, which revolved around the complexities of an arranged marriage, was not only a commercial success but also set a precedent for script-based Chinese films.

However, the journey was not without its bumps. The onset of World War I disrupted their momentum, leading them to explore other ventures, from managing theatre troupes to running newspapers. But their early success acted like a siren for them, too tempting to resist. By 1922, Zhang and Zheng, along with a few friends, founded Mingxing, a film company that aimed to rival Western productions. Their vision was clear: to create films that educated and entertained the masses. While Zheng believed in the transformative power of cinema, Zhang, ever the pragmatist, advocated for commercial comedies.

Mingxing’s Golden Age

1922 was a pivotal year for Mingxing. They released a trilogy of shorts, drawing inspiration from American comedies like those by Charlie Chaplin, including “Laborer’s Love”. However, it was their 1923 drama, “Orphan Rescues Grandpa,” that truly cemented their place in Chinese cinema. The heartwarming tale of a boy reuniting with his estranged grandfather resonated deeply with audiences, propelling Mingxing to the forefront of the industry.

The duo’s success continued with the release of “The Burning of Red Lotus Temple” in 1928, a wuxia epic that captivated audiences with its thrilling action sequences and special effects. The film’s impact was so profound that it led to a surge in wuxia films, much to the chagrin of intellectuals and authorities. Concerns over the genre’s influence even led to its ban by the Chinese government in 1931, but this is ultimately where the genre began, eventually becoming big business in the Shaw Brothers’ Hong Kong studios.

The 1930s were a time of innovation and change for Mingxing. They produced China’s first sound film, “Sing-Song Girl Red Peony,” and tackled pressing societal issues with films like “Spring Silkworms” and “Twin Sisters.” However, this golden age was short-lived. The untimely death of Zheng in 1935, coupled with financial and censorship challenges, marked the beginning of the end for Mingxing. The final blow came with the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War in 1937, which culminated in the studio’s closure in 1939.

For Zhang, the war years were tumultuous. While he continued to work in the film industry, his association with the Japanese-controlled China United Film Production Corporation tarnished his reputation. Accusations of treachery plagued him, casting a shadow over his illustrious career. The weight of collaboration with Japan affected his reputation and that of Mingxing for decades. Zhang’s final years were spent oscillating between Hong Kong and Shanghai, with his death in 1953 marking the end of an era.

Unfortunately, most of their films are lost. However, that doesn’t mean they’re forgotten. They’re not held up to the same level as other pioneers of the medium, but they started the first generation of Chinese directors and incubated the second.