Stanley Kramer was an American film director and producer renowned for his filmography, mainly comprised of ‘message films’ that straddled both the Golden Age and New Wave of Hollywood cinema. He established a formidable reputation as a socially-conscious filmmaker, tackling a wide range of controversial issues during a time when many other directors shied away from such subject matter. Kramer’s legacy is solidified by several seminal works, including Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, Inherit the Wind, and Judgment at Nuremberg which explore, respectively, interracial marriage, the clash between creationism and evolution, and the ethical responsibility of individuals during war.

Kramer’s filmography stands out for its audacious engagement with pressing social and political issues. A common motif in his films is the challenge to prevailing societal norms, often framing stories around individuals standing against the tide of popular opinion. He has been celebrated for his uncanny ability to strike a balance between creating commercially successful films that appeal to mainstream audiences while also infusing them with profound messages and thought-provoking narratives. On the Beach, for instance, examines the existential threat of nuclear warfare, while The Defiant Ones delves into themes of racial discrimination and unity. Kramer’s cinematic approach can be characterised as unflinchingly bold and insistent, choosing to spotlight societal issues rather than gloss over them, which makes his oeuvre both profound and enduring.

Kramer’s style was defined by a kind of restrained flamboyance. His films usually feature meticulous framing and composition, which often serve to enhance the thematic undercurrents of his stories. In Judgment at Nuremberg, for instance, the use of stark black-and-white cinematography underlines the gravity of the historical trial it depicts. Kramer was also known for his knack for eliciting powerful performances from his actors, which adds a layer of emotional intensity to his films. His influence can be seen in later filmmakers who adopt similar approaches of balancing commercial success with societal commentary. Despite his films’ commercial and critical success, Kramer was often described as a “filmmaker’s filmmaker”, praised more by his peers than by critics.

Stanley Kramer (1913 – 2001)

Calculated Films:

- The Defiant Ones (1958)

- On The Beach (1959)

- Inherit the Wind (1960)

- Judgment at Nuremberg (1961)

- It’s A Mad Mad Mad Mad World (1963)

- Guess Who’s Coming To Dinner (1967)

Similar Filmmakers

Stanley Kramer’s Top 5 Films Ranked

1. Judgment at Nuremberg (1961)

Genre: Legal Drama, Period Drama

2. Inherit The Wind (1960)

Genre: Legal Drama

3. It’s A Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World (1963)

Genre: Comedy, Adventure, Road Movie, Slapstick

4. Guess Who’s Coming To Dinner (1967)

Genre: Drama, Romance, Family Drama

5. The Defiant Ones (1958)

Genre: Crime, Drama, Buddy

Stanley Kramer: Holding a Mirror to Mid-Century America

Stanley Kramer was the king of message films. They existed before and after him, but nobody made films that spoke to social and political problems like his. From racial divides to the world’s end, Kramer addressed mid-century America’s issues. However, his was an unlikely story as he was born in 1913 to Jewish immigrants in the teeming streets of Manhattan, where he first became passionate about social justice by watching the challenges faced by minority communities.

Kramer worked hard, eventually going to New York University and then working assorted jobs in pre-war Hollywood. However, during World War Two, Kramer got his first taste for making films about genuine issues while in the U.S. Army Signal Corps. Upon returning from the war, he set up his own production company to address the sort of social issues the big studios avoided.

He was a phenomenally successful producer with a knack for identifying projects, discerning talents and understanding the audience. Among the many films he produced were films like Champion, which introduced Kirk Douglas to a wider audience and marked Kramer’s commitment to intricate character studies.

But it was High Noon where Kramer really made his mark on Hollywood. Although garbed as a Western, this film was a bold allegory of the McCarthy era, exploring themes of loyalty, honour, and societal ostracisation. At a time when Hollywood was under the scrutinising gaze of the House Un-American Activities Committee, High Noon stood out as a beacon of quiet resistance. Its iconic imagery, with Gary Cooper’s solitary marshal facing down a gang of outlaws, symbolised the individual’s struggle against oppressive majoritarian forces.

Kramer wasn’t satisfied simply producing, so he decided instead to direct, starting in 1955 with Not as a Stranger, which, though not universally lauded, showcased Kramer’s potential. The Defiant Ones first made it clear Kramer was a director worth paying attention to. The film, a gripping tale of two escaped convicts, one black and one white, shackled together, explored the raw, uncomfortable terrain of racial prejudices. Both Tony Curtis and Sidney Poitier delivered memorable performances, with the latter breaking numerous barriers in the process.

In 1959, Kramer directed On The Beach, a dystopian portrayal of the post-nuclear world, which further showcased his penchant for exploring socio-political themes. With a star-studded cast including Gregory Peck and Ava Gardner, the film’s haunting narrative and evocative imagery served as a stark warning against nuclear proliferation.

Arguably, one of Kramer’s most critically acclaimed directorial endeavours, Inherit the Wind, came on the heels of his previous successes. It was a fictionalised account of the 1925 Scopes “Monkey” Trial, wherein a teacher was tried for teaching evolution in a Tennessee school. The film, with its powerful dialogues and intense courtroom drama, touched upon the ever-pertinent theme of science versus religion, freedom of thought, and the dangers of blind fanaticism. With powerhouse performances from Spencer Tracy and Fredric March, the film proved to be a commercial and critic hit and would become something of a template for Kramer.

Perhaps Kramer’s most important film is Judgment at Nuremberg, which bore the heavy weight of historical trauma. Set against the backdrop of the Nuremberg Trials post-World War II, this film sought to grapple with the enormity of the Holocaust and the complicity of those who allowed it to happen. With an ensemble cast featuring Burt Lancaster, Richard Widmark, Maximilian Schell, and Judy Garland, the film was a relentless exploration of morality, accountability, and the cost of silence in the face of injustice. It was essentially Kramer’s clarion call for humanity to confront its darkest moments and one of the first serious attempts by a Hollywood studio to engage the holocaust.

Shifting gears dramatically, Kramer took on a mammoth comedy project in 1963: It’s a Mad Mad Mad Mad World. This slapstick epic, bursting with comedic legends like Spencer Tracy, Milton Berle, Ethel Merman, and Jonathan Winters, showcased Kramer’s versatility. It was a sprawling, madcap chase for hidden treasure and perhaps the ultimate showcase for classic Hollywood comedy. Though a departure from his usual hard-hitting themes, the film was evidence that Kramer could masterfully weave any narrative thread.

Around this period, Kramer also offered Ship of Fools, an evocative portrayal of the various passengers aboard a ship bound for Germany, subtly highlighting the world’s descent into chaos on the brink of World War II.

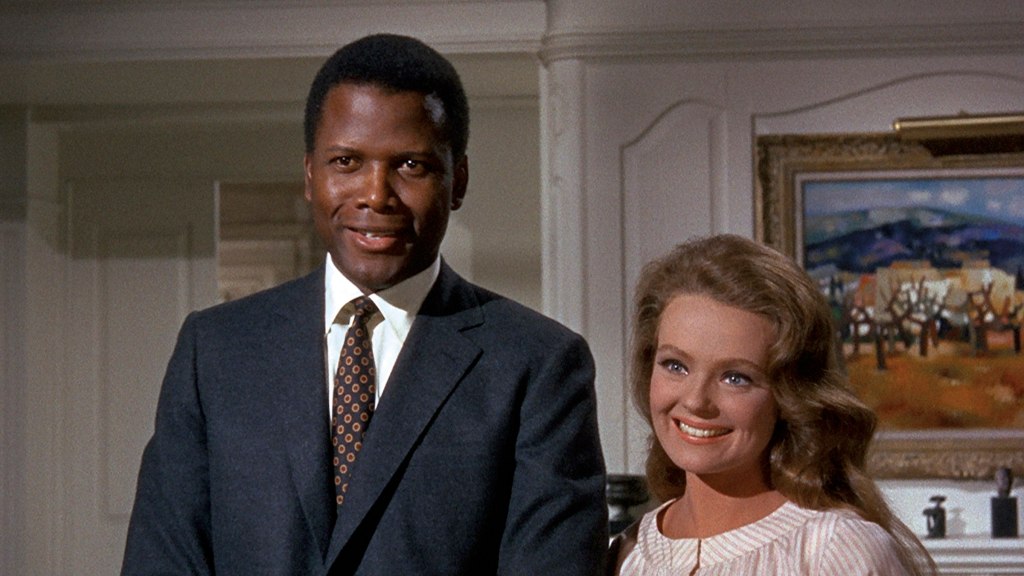

In 1967, at the height of the Civil Rights Movement, Kramer delivered Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, a socially important film addressing interracial relationships. With Sidney Poitier, Katharine Hepburn, and Spencer Tracy leading the cast, the movie navigated the complexities of love, race, and generational divides with grace and nuance. It was timely, significant, and resonated deeply with audiences navigating a changing racial landscape in America.

As the 1970s approached, Kramer’s directorial ventures began to wane in their impact. Films like The Secret of Santa Vittoria and Oklahoma Crude received mixed reviews, often criticised for lacking the edge and intensity that had become synonymous with Kramer. His last directorial venture, The Runner Stumbles, a courtroom drama revolving around the trial of a priest accused of murdering a nun, went largely unnoticed, marking a subdued end to an otherwise illustrious directorial career.

Throughout his career, Stanley Kramer worked in various genres, but one constant was his devotion to the ‘message film.’ A sub-genre focused on addressing societal issues, challenging norms, and prompting viewers to question their beliefs and values. His unwavering commitment to using cinema as a social commentary tool was his strength and, occasionally, his Achilles’ heel. Critics sometimes chastised him for being overtly didactic, yet no one could deny the courage it took to craft films that made audiences question, introspect, and debate.

Most Underrated Film

While Judgment at Nuremberg is, without question, among Stanley Kramer’s most acclaimed works, it surprisingly doesn’t frequently top lists recounting the greatest films of the 1960s. In retrospect, the film feels like a product of the 1950s, with its large ensemble cast and distinct preachy vibe, factors that might have inadvertently made it seem somewhat anachronistic.

The production of Judgment at Nuremberg was a mammoth undertaking. Set against the backdrop of the post-World War II Nuremberg Trials, it aimed to confront the heinous crimes of the Holocaust, offering a deep dive into moral dilemmas, personal and collective accountability, and the grave costs of complacency. Kramer assembled a cinematic tour-de-force for the film, with stellar performances from Burt Lancaster, Maximilian Schell, and Judy Garland, among others.

One particular scene that stands out is the exchange between Schell and Lancaster, wherein Lancaster’s character, a judge, grapples with his role in enabling the atrocities. This scene’s emotional intensity, rawness, and ethical conflict epitomise the film’s depth.

Stanley Kramer: Themes and Style

Themes:

- Social Issues: Kramer was often drawn to films that wrestled with the pressing social issues of the day. Race relations (Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner), the threat of nuclear war (On The Beach), and the Holocaust (Judgment at Nuremberg) are just a few of the topics he tackled head-on.

- Moral Dilemmas: Many of Kramer’s films put characters in situations where they must grapple with ethical questions, often involving societal pressures versus personal beliefs.

- Individual vs. Society: Films like High Noon and Inherit the Wind showcase the struggle of individuals against the larger community or system, often emphasising the courage required to stand against the tide.

Styles:

- Ensemble Casts: Many of Kramer’s films employed a vast ensemble of actors, making his productions rich tapestries of characters and narratives.

- Message-Driven Narratives: Often termed ‘message films’, Kramer’s movies typically had a strong moral or societal argument at their core, making them as thought-provoking as they were entertaining.

- Dramatic Intensity: Kramer had an uncanny ability to create tension and drama, often using extended sequences (like the courtroom scenes in Judgment at Nuremberg) to build emotional depth.

Directorial Signature:

- Extended Dialogue Scenes: Kramer was known for lengthy, dialogue-heavy scenes, which, while sometimes criticised for being overly verbose, allowed his characters to thoroughly explore and debate the issues at hand.

- Black-and-White Filmmaking: Although colour became the norm, Kramer often chose black-and-white filming to add gravitas and timeless quality to his narratives.

Further Reading:

Books:

- Stanley Kramer: Film Maker by Donald Spoto – This book provides an in-depth look at Kramer’s career, shedding light on his professional journey and motivations.

- It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World: A Life in Hollywood by Stanley Kramer – In his autobiography, Kramer reflects on his experiences and challenges in Hollywood, providing personal insights into his films.

Articles and Essays:

- Why Was Stanley Kramer So Unfashionable at the Time of His Death? by David Walsh, WSWS

- Filmmakers’ Autobiographies: Stanley Kramer’s Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World by Jean-Paul Chaillet, Golden Globes

- Message Movies by Terrence Rafferty, Director’s Guild of America

Stanley Kramer – Great Director