Nicholas Ray was an American filmmaker renowned for his keen exploration of character psychology and striking visual style. While his mastery of genre-blending is apparent, it is perhaps the emotional intensity of his melodramas and the complexity of his characters that truly define his work. Ray’s films, characterised by an empathetic portrayal of outsiders and nonconformists, tackled social issues with an honesty that was groundbreaking at the time. His most famous film, Rebel Without a Cause, is a seminal exploration of teenage angst, and it continues to resonate with audiences even today.

Ray began his career in the theatre and radio before moving on to Hollywood, where he worked as an assistant before getting the opportunity to direct. His early life experiences, marked by frequent travel and a diverse range of jobs, seem to have influenced his cinematic preoccupation with characters who exist on the fringes of society. His protagonists are often people grappling with their desires, emotions, societal expectations, and sense of alienation.

Ray was a master of melodrama, adept at blending it seamlessly with other genres like film noir, westerns, and teen films. His stories often revolved around outsider characters, reflecting his fascination with themes of nonconformity and alienation. Ray’s films are imbued with emotional intensity, featuring characters caught in existential struggles, tormented by their feelings and the pressures of societal norms. Films like In a Lonely Place and Johnny Guitar exemplify his adept handling of complex character dynamics and intense emotional themes.

CinemasScope Master

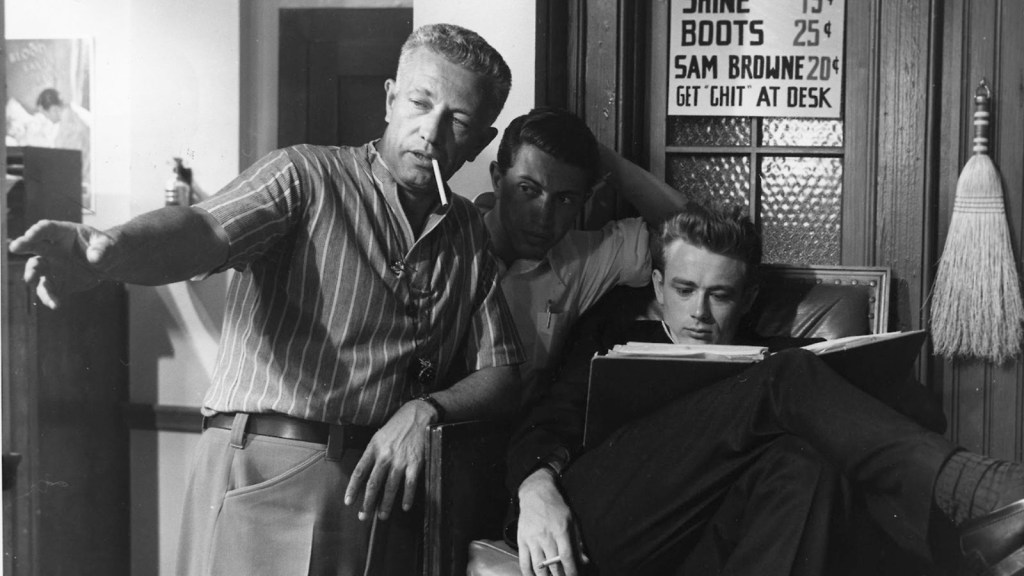

In terms of visual style, Ray was known for his innovative use of colour, composition, and the widescreen format CinemaScope. He employed techniques such as unusual angles, dramatic lighting, and wide compositions to intensify the emotional impact of his films. His close collaborations with stars like James Dean and Natalie Wood led to some memorable and intense performances, further enhancing the emotional resonance of his films.

Ray’s approach to social themes was both bold and nuanced. His films confronted issues of masculinity, femininity, sexuality, and the often stifling norms of society. Despite their initial lack of commercial success, many of Ray’s films, including Bigger Than Life, have been critically reappraised, earning recognition for their subtle social commentary and forward-thinking perspectives.

The influence of Nicholas Ray’s work stretches far beyond Hollywood, reaching filmmakers worldwide. He left a significant mark on the French New Wave directors, with Jean-Luc Godard famously stating, “Cinema is Nicholas Ray.” His innovative use of widescreen compositions and his complex, psychologically rich characters have also influenced contemporary directors like Martin Scorsese and Wim Wenders. Despite the ups and downs of his career, Ray’s legacy remains intact, and he continues to be recognised as a seminal figure in American cinema, one whose work is marked by emotional depth, visual innovation, and a unique understanding of the human condition.

Nicholas Ray (1911 – 1979)

Calculated Films:

- They Drive By Night (1948)

- In A Lonely Place (1950)

- On Dangerous Ground (1951)

- The Lusty Men (1952)

- Johnny Guitar (1954)

- Rebel Without A Cause (1955)

- Bigger Than Life (1956)

- Lightning Over Water (1980)

Similar Filmmakers

Nicholas Ray’s Top 10 Films Ranked

1. In A Lonely Place (1950)

Genre: Film Noir, Drama, Romance, Mystery

2. Johnny Guitar (1954)

Genre: Revisionist Western

3. Bigger Than Life (1956)

Genre: Psychological Drama, Melodrama, Family Drama

4. They Live By Night (1948)

Genre: Crime, Romance, Film Noir, Drama

5. Rebel Without A Cause (1955)

Genre: Coming-of-Age, Drama, Teen Movie, Melodrama

6. The Lusty Men (1952)

Genre: Neo-Western, Drama, Sports

7. On Dangerous Ground (1951)

Genre: Film Noir, Drama, Crime

8. Bitter Victory (1957)

Genre: War, Drama

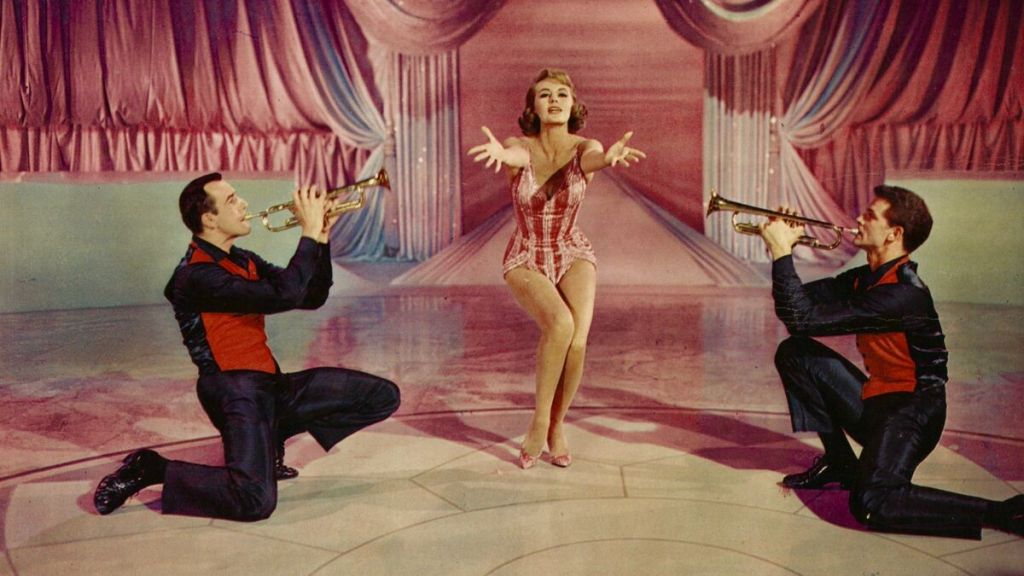

9. Party Girl (1958)

Genre: Gangster Film, Drama, Melodrama

10. Lightning Over Water (1980)

Genre: Movie Documentary, Essay Film

Nicholas Ray: A Rebel Within Classic Hollywood

Nicholas Ray, born Raymond Nicholas Kienzle on August 7, 1911, in Galesville, Wisconsin, was a harbinger of a new era of movies. A weirdo in a conformist land who almost blended in yet stuck out like a sore thumb for those who knew what to look for. Like the greats of the studio system, he wielded its power to explore the human psyche and dive deep into society’s dark and unexplored recesses.

Growing up in the lush surroundings of Wisconsin, Ray had an inkling of artistic pursuits early in his life. His formative years were marked by experimentation with theatre and architecture. Mentored by Frank Lloyd Wright, Ray’s architectural pursuit laid the foundation for his future in film, for his way of looking at space and form would translate into a distinctly visual cinematic language.

His entry into the world of film was anything but ordinary. From radio to theatre, Ray’s journey was marked by curiosity and an unquenchable thirst for creative exploration. He found himself working under the tutelage of Elia Kazan, a partnership that would shape Ray’s understanding of the actor’s craft and the power of emotional storytelling.

Ray’s directorial debut, They Live by Night, was a signal flare, announcing the arrival of a filmmaker who wouldn’t conform to Hollywood’s shimmering façade. The film was a passionate love story and a crime drama, blurring the lines between good and evil, love and despair. The raw intensity of the characters was a revelation; Ray painted them with a brush dipped in both compassion and tragedy.

In 1950, In a Lonely Place saw Ray delve into human nature’s darkness once more, presenting a character study wrapped in a noirish mystery. Humphrey Bogart’s portrayal of a troubled screenwriter was both alarming and heartbreaking, reflecting Ray’s gift for extracting the profound from the mundane.

But it was Rebel Without a Cause that catapulted Ray into the echelons of pop culture history. Starring James Dean, the film was more than a teen drama; it was a sociological study, an elegy for a disillusioned generation. The angst, the frustration, the longing for connection, Ray captured it all in vivid Technicolor. The film resonated with youth worldwide, turning Nicholas Ray into an emblem of cultural rebellion.

His films from this period were laced with a sense of social defiance, a mirror reflecting the seismic changes of post-war America. Whether it was the anti-McCarthyism of On Dangerous Ground or the feminist undertones of Johnny Guitar, Ray’s cinema was a statement, a cry against conformity and societal suppression.

Ray’s approach to filmmaking was not confined to a genre or style; he was a cinematic alchemist, turning seemingly straightforward narratives into intricate examinations of human behaviour. He wasn’t afraid to experiment with form and content, pushing the boundaries of what was considered acceptable or palatable. His courage to explore, dissect, and question made him a daring provocateur in a conformist society.

Yet, beneath the bold exterior, Ray’s films were imbued with a melancholy and tenderness that spoke to the fragility of human existence. His characters were lost souls wandering through the wilderness of life, seeking redemption, love, and understanding. In Ray’s world, they found a voice, an expression, a validation of their struggles.

The 1960s marked a shift in Hollywood, both culturally and commercially. For Nicholas Ray, it was a period of personal and professional metamorphosis as he grappled with the tension between artistic integrity and the industry’s evolving demands.

Ray’s 1961 film King of Kings was a foray into the biblical epic, a genre that might have seemed at odds with his earlier works. Yet, Ray’s depiction of Jesus Christ was nuanced and deeply human, imbuing the film with a spiritual resonance that transcended mere spectacle. However, the challenges of producing such a grand-scale project hinted at the struggles Ray would face in his career.

Following King of Kings, Ray embarked on an ambitious project, 55 Days at Peking. Plagued by production issues and personal health struggles, the film symbolised Ray’s clash with the Hollywood system. His vision was compromised, his authority undermined, and Ray’s once untamed creativity seemed to be stifled by the very industry that had once embraced him.

The latter half of the 1960s saw Ray drifting away from mainstream Hollywood, seeking solace in European cinema and academia. His films from this period, including We Can’t Go Home Again, reflected a deeper introspection, a search for meaning beyond the confines of commercial cinema, revealing Ray’s deep disillusionment with Hollywood.

Teaching at institutions like the State University of New York at Binghamton, Ray’s influence extended beyond the silver screen. He became a mentor to a new generation of filmmakers, including collaborator Wim Wenders, imparting his wisdom and encouraging them to challenge the status quo. In the classroom, Ray’s spirit of rebellion found a new outlet, inspiring young minds to see the world through a different lens.

Ray’s later years were marked by a sense of isolation and a longing to reconnect with his artistic roots. His health deteriorated, but his passion for storytelling remained undiminished.

Nicholas Ray passed away on June 16, 1979, but his legacy endures, a testament to his unyielding pursuit of truth and authenticity. His films are more than mere entertainment; they are cultural artefacts, windows into a world grappling with change, fear, hope, and love.

Nicholas Ray’s contribution to cinema goes beyond his individual films. He was a philosopher with a camera, a poet of the human condition, a chronicler of his times. His refusal to be boxed into stereotypes, courage to defy norms, and empathy for the misfits and outcasts made him a true cinematic visionary. Ray’s work resonated globally, influencing filmmakers across continents. From Jean-Luc Godard to Martin Scorsese, his fingerprints can be found in the works of directors who would redefine cinema in the years to come.

In an era of conformity, Nicholas Ray was an anomaly, a beacon of individuality and creativity. His films continue to inspire, provoke, and awaken, a timeless celebration of the human spirit’s ability to transcend, feel, and rebel.

Such was the life of Nicholas Ray, a filmmaker whose name will forever be synonymous with cinematic courage, artistry, and transcendence.

Most Underrated Film

Once upon a time, every Nicholas Ray film was substantially underrated. People thought Johnny Guitar was a waste of time and They Live By Night was a throwaway B-movie. Nowadays, most of Ray’s films have an audience. Some comfortably fit the title of underrated, such as Party Girl and Bitter Victory, but the pick we’ve chosen is Bigger Than Life.

Bigger Than Life is a fairly well-regarded film, so it doesn’t neatly fit into the underrated category; most people see it as one of his better films, but it isn’t nearly as spoken about as Rebel Without A Cause or In A Lonely Place.

Starring James Mason as Ed Avery, a school teacher diagnosed with severe arterial disease, the film explores the tragic consequences of his treatment with cortisone, a then-new wonder drug. The drug’s side effects unravel Avery’s psyche, transforming him from a loving father and husband into a megalomaniac.

Bigger Than Life was more than a mere medical drama; it was a scathing critique of American consumerism, the ideal of the nuclear family, and the growing dependence on pharmaceuticals. Ray’s direction was as subtle as it was incisive, painting a horrifying portrait of a man undone by societal pressures and medical intervention.

The film’s visual aesthetic is striking, with Ray’s architectural background coming to the fore. He employs colour, shadow, and space to create an atmosphere that’s at once surreal and all too real. The cinematic techniques in Bigger Than Life serve not just to tell the story but to embody the emotional and psychological state of the characters.

James Mason’s performance is a tour de force, capturing the complexity of a man grappling with a sense of inadequacy, only to be propelled into madness by a supposed miracle cure. His descent into tyranny is not just a personal tragedy but a reflection of the darker undercurrents of 1950s America.

Despite its brilliance, Bigger Than Life was a commercial failure upon release, and its bold themes were met with resistance. The film’s critique of medical practices, domestic life, and societal norms may have been too ahead of its time, causing audiences to overlook its deeper significance.

Nicholas Ray: Themes & Style

Themes:

- Outsiders and Rebellion: Many of Ray’s films centre around characters who feel alienated or are in direct conflict with societal norms. From Rebel Without a Cause to Johnny Guitar, the focus on outsiders and rebels reflects Ray’s own sense of nonconformity.

- Human Emotion and Psychological Complexity: Ray delved deeply into the human psyche, exploring emotions, mental health, and complex relationships. Bigger Than Life is a prime example of his interest in human fragility and instability.

- Social Critique: Often critiquing American culture, Ray’s films analyse various societal aspects, such as consumerism, gender roles, and the family structure. These critiques are subtly woven into his narratives, making the audience ponder broader societal issues.

Styles:

- Visual Aesthetics: With an eye for architectural detail, Ray’s visual style was marked by the strategic use of colour, shadow, and composition. He often utilised cinemascope, creating visually striking scenes that added layers to his storytelling.

- Character-Driven Narratives: Ray’s films are celebrated for their rich character development. Whether leading or supporting roles, characters are multi-dimensional and central to the narrative.

- Realism and Expressionism: Ray’s approach often blended realistic settings with expressive techniques, balancing everyday life with heightened emotion and stylised visuals.

Directorial Signature:

- Empathetic Storytelling: Ray’s approach was deeply empathetic, often siding with the characters who were marginalised or misunderstood. He handled characters with care, allowing them to be flawed yet deeply human.

- Complex Female Characters: Unlike many of his contemporaries, Ray presented women in strong, complex roles. His female characters had agency and were often essential to the plot, reflecting his progressive views on gender.

- Interweaving Genres: Ray had an ability to transcend and combine different genres, making his films difficult to categorise. From noir to Western to drama, his films often blur the lines between traditional genres.

- Collaboration with Actors: Known for his close association with actors, Ray allowed them to explore and contribute to their roles, creating authentic and resonant performances.

- Musical Choices: Ray’s use of music was often innovative and integral to his films. He employed music not just as a background element but as part of the narrative fabric, enhancing the emotional depth of his films.

Further Readings:

Books:

- Nicholas Ray: An American Journey by Bernard Eisenschitz – A comprehensive biography and analysis of Ray’s filmography.

- I Was Interrupted: Nicholas Ray on Making Movies edited by Susan Ray – A collection of Ray’s own writings, lectures, and interviews.

- The Films of Nicholas Ray by Geoff Andrew – A critical examination of Ray’s films.

Articles and Essays:

- Why Nicholas Ray is in a class of his own by Geoffrey McNab, The Guardian

- In Re: Nicholas Ray by Richard Brody, The New Yorker

- Reclaiming Causes of a Filmmaking Rebel by Patricia Cohen, New York Times

- The Strange Case of Nicholas Ray by Terrence Rafferty, Director’s Guild of America

- Ray, Nicholas by Jonathan Rosenbaum, Senses of Cinema

Documentaries:

- Don’t Expect Too Much (2011) – Directed by Ray’s widow, Susan Ray, this documentary explores Ray’s unfinished project, “We Can’t Go Home Again” and provides insights into his creative process.

Nicholas Ray: The 68th Greatest Director