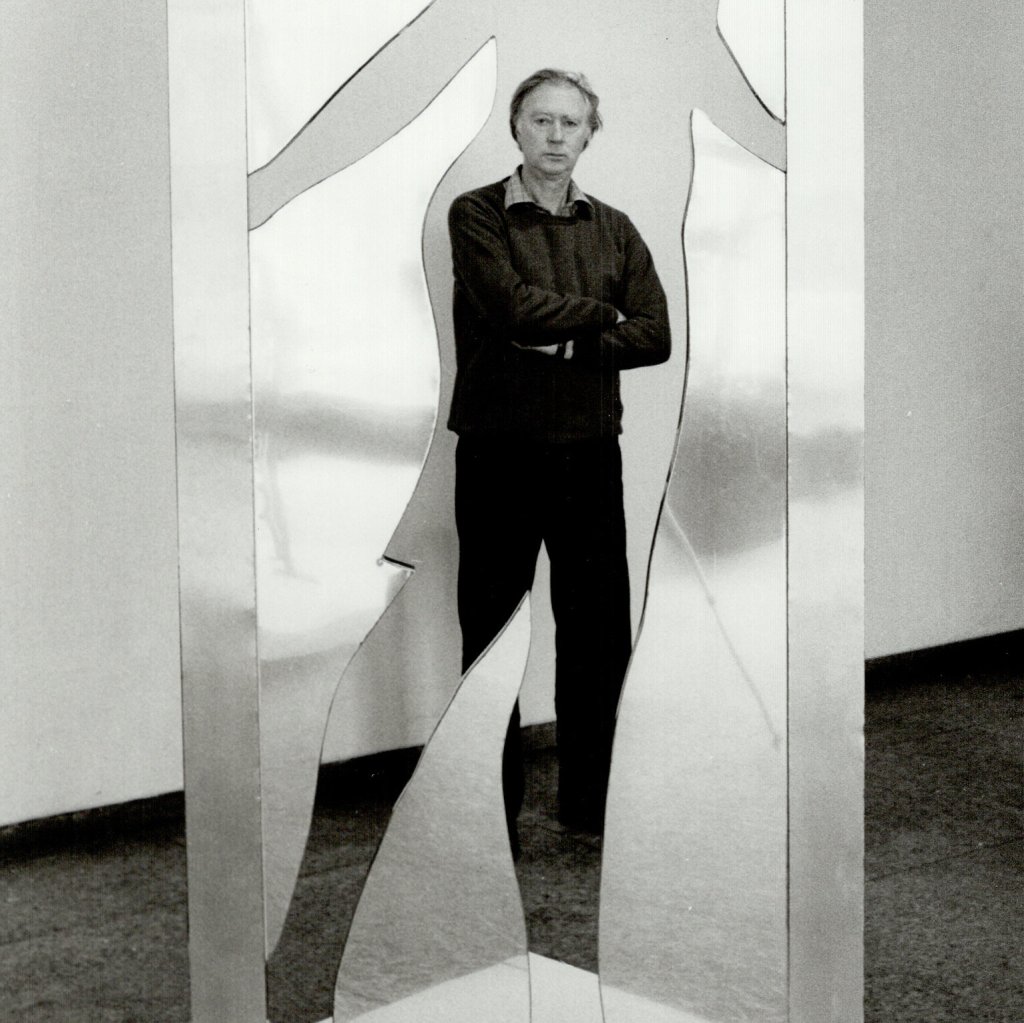

Michael Snow was a Canadian artist and experimental filmmaker whose contribution to avant-garde cinema has been pioneering and influential. His diverse work spans several mediums: painting, sculpture, video, films, photography, holography, drawing, books, and music. However, he is best known for his experimental films, such as Wavelength, La Région Centrale, and Back and Forth, which challenged traditional narrative structures and reshaped the understanding of cinematic language.

Snow’s films recurrently explore the relationship between time, perception, and cinematic apparatus. In many of his works, he has questioned the concept of cinema as a medium for narrative storytelling, instead turning the attention to its structural aspects. For instance, Wavelength uses a continuous zoom to create a 45-minute-long exploration of space within a single room. Similarly, La Région Centrale revolves around a specially constructed mechanical arm that allows the camera to move in virtually any direction, creating a film devoid of human intervention. His approach to filmmaking is decidedly experimental, often focusing on manipulating fundamental film elements such as time, movement, and perspective.

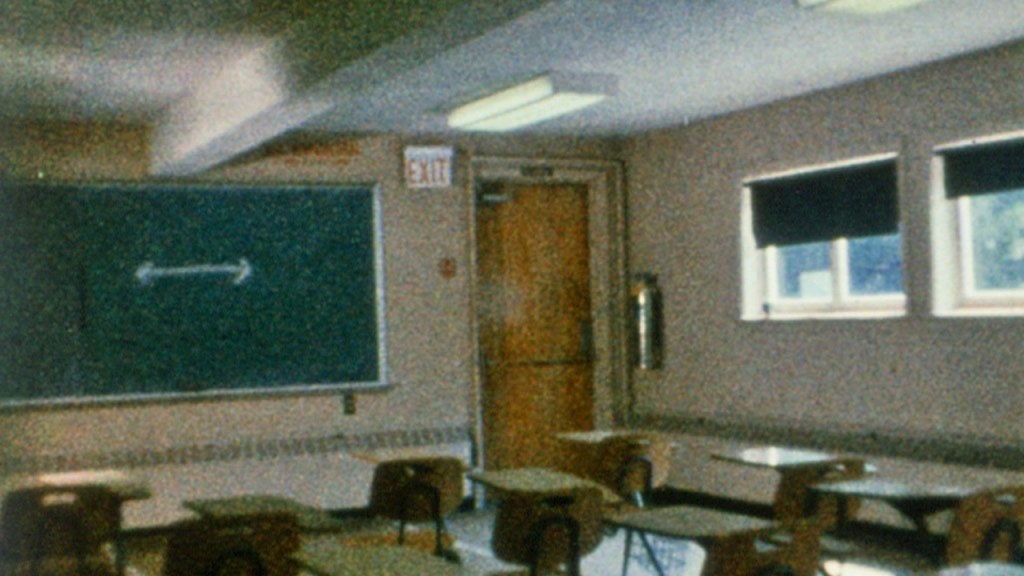

Snow’s style focuses on formalistic exploration rather than conventional narrative structure. His films often employ minimalistic yet innovative techniques, creating a unique viewing experience. For instance, Back and Forth features repetitive panning movements that evolve into a rhythmic, almost hypnotic pattern, exploring the notions of time and space purely through camera motion. His approach towards cinema is rooted in a deep investigation of its basic elements, and he consistently pushes the boundaries of what can be expressed through the medium.

Snow’s impact on cinema is monumental, particularly in experimental and avant-garde films. His unique approach to filmmaking has expanded the understanding and potential of cinema, inspiring generations of filmmakers and artists. While his films may not conform to mainstream cinematic conventions, they offer a radical exploration of the medium’s possibilities, making Snow a crucial figure in the history of experimental cinema.

Michael Snow (1928 – 2023)

Calculated Films:

- Wavelength (1967)

- La Region Centrale (1971)

Similar Filmmakers

- Andy Warhol

- Bruce Baillie

- Chris Marker

- David Rimmer

- Hollis Frampton

- James Benning

- Jonas Mekas

- Joyce Wieland

- Ken Jacobs

- Kenneth Anger

- Malcolm Le Grice

- Maya Deren

- Nathaniel Dorsky

- Paul Sharits

- Peter Kubelka

- Stan Brakhage

- Takahiko Iimura

- Tony Conrad

5 Michael Snow Films You Need To See

Wavelength (1967)

Genre: Structural Film

Back and Forth (1969)

Genre: Structural Film

La Region Centrale (1971)

Genre: Structural Film

‘Rameau’s Nephew’ by Diderot (Thanx to Dennis Young) by Wilma Schoen (1974)

Genre: Structural Film

*Corpus Callosum (2002)

Genre: Structural Film, Surrealism, Video Art, Satire

Michael Snow: Beyond the Conventional Camera

By the 1950s, Michael Snow plunged headfirst into the vibrant world of abstract expressionism, a movement that championed spontaneous and subconscious creation. This was a time when artists such as Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning were redefining the boundaries of artistic expression. With his fearless approach, Snow soon became part of this revolutionary movement.

Snow’s abstract works imbued with a dynamic energy, often reflected his keen observation of movement and transformation. Whether it was his choice of bold colour palettes or the aggressive strokes that dominated his canvases, Snow’s artistry was a testament to his commitment to pushing the boundaries of conventional art.

While his paintings were gaining attention and praise in the art community, Snow’s unquenchable thirst for experimentation led him down a new path: the world of film.

The late 1950s and early 1960s marked a period of intense experimentation in cinema worldwide. Ever the pioneer, Snow began to see the medium of film as an extension of his abstract expressionist sensibilities. This period saw him transition from static canvases to dynamic, moving pictures, blurring the lines between conventional film narratives and avant-garde art.

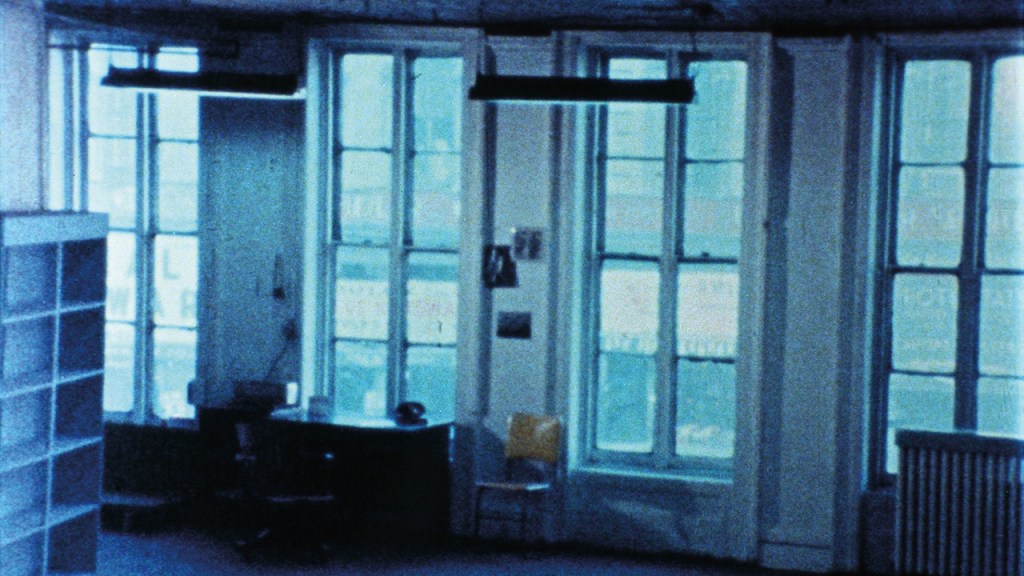

Film became a canvas where he could manipulate time, space, and perception. In 1967, Snow released his most iconic and transformative work: Wavelength. Over its 45-minute duration, the film consists of a singular, continuous zoom into a room. It’s a simple yet profound exploration of space and time. The film’s audacity lies in its simplicity, and it was met with both bafflement and awe. The minimalistic soundtrack, a continuous sine wave, further intensifies the experience, making the film a visual and auditory journey.

While some critics dismissed it as overly esoteric, others saw it as a groundbreaking piece of art, a film that questioned the very nature of cinema. The film won the Grand Prize at the Knokke Experimental Film Festival, cementing Snow’s reputation.

Michael Snow’s Wavelength was a pivotal moment in the broader movement known as Structural Film. This genre sought to dismantle traditional film narratives and reconstruct them in novel ways, focusing on the properties of a film itself rather than the content. With his background in abstract expressionism and his radical approach to film, Snow became one of the central figures in this movement.

1971 saw Snow delving into the vast landscapes of Northern Quebec with his film La Région Centrale. Over its three-hour duration, the film captured panoramic views using a specially designed rotating camera, generating a series of intricate patterns and formations. Snow’s intent was to present an environment untouched by human intervention, where the mechanical gaze of the camera became the only mediator.

Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, Snow continued to refine his unique cinematic language. Films such as Breakfast (Table Top Dolly) and So Is This further solidified his reputation as an avant-garde maestro. His movies often oscillated between being profoundly minimalistic and intensely layered, consistently challenging viewers and critics alike. These works’ meta-filmic commentary, long takes, and experimental soundscapes forced audiences to confront the very nature of film viewing, blurring the line between passive consumption and active engagement.

Despite his cinematic triumphs, Snow’s oeuvre extended well beyond the silver screen. His sculptural series, “Walking Women,” became one of the most recognizable motifs in contemporary art. These silhouetted figures, cut out from photographs and placed in various settings, highlighted Snow’s fascination with movement, perception, and the play of shadows.

Furthermore, Snow’s installations were as revolutionary as his films. Often large-scale and immersive, they created environments where the viewer became an intrinsic part of the artwork. Snow’s mastery lay in creating an interactive experience, making the observer acutely conscious of their position in space and time.

In the early 2000s, Michael Snow again showcased his avant-garde brilliance with Corpus Callosum. With its unique blend of digital effects and organic elements, this film is a vibrant exploration of duality — between technology and nature, between the tangible and the ethereal. It’s a visual treat, with sequences that stretch and distort reality, hinting at the ever-evolving dynamics of human perception in an increasingly digital world.

Michael Snow isn’t an easy director to love. His films offer no set pieces or dazzling character studies. They’re built to challenge, and ultimately, you only get out of them what you are willing to put in. Snow never stopped challenging, evolving or provoking. He was one of the great avant-garde figures of the medium, without whom cinema would be a stale and boring place.

Most Underrated Film

There are plenty of reasons to dislike Wavelength. It’s excessively esoteric, stretched out, monotonous and inaccessible. It’s easy to say, “OK, I get the point of it,” but it’s hard to connect with it. This thought process has resulted in the film generally being bypassed by even the biggest cinephile, but it is worth more than a cursory glance.

Crafted in 1967, Wavelength is a masterclass in production restraint. The film lacks elaborate sets, actors, or dialogue, relying instead on the camera’s singular, deliberate movement. Such a production approach, devoid of distractions, compels the viewer to confront the essence of cinema: time, space, and perception.

By stretching time, Snow amplifies moments of transition and transformation. A particular scene, where a woman briefly appears, collapsing, and the subsequent entrance of two people who react to the situation becomes amplified amidst the film’s vast silences and deliberations. It’s a simple yet powerful commentary on the transient nature of life juxtaposed against the inexorable passage of time.

While potentially polarizing, the film remains the finest proof of Snow’s audacious approach to cinema. It challenges, provokes, and ultimately rewards those willing to engage with its depths.

Michael Snow: Themes and Style

Themes:

- Perception and Reality: Snow constantly played with the idea of what is real and perceived, pushing audiences to question their understanding and engagement with art.

- Time and Space: A recurring motif in Snow’s work is exploring the passage of time and the essence of space. Films like Wavelength and La Région Centrale are quintessential examples of this theme.

- Human Interaction with Art: Snow often forced his audience to become a part of the narrative or art piece, blurring the line between observer and participant.

- Movement and Stasis: Snow juxtaposed dynamic movement with static imagery, creating tension and balance in his art and films.

Styles:

- Experimental Soundscapes: Snow’s work frequently incorporated avant-garde sound elements. The use of sine waves in Wavelength or the organic sounds in Corpus Callosum attest to his sonic experimentation.

- Long Takes: Snow was known for extensively using long, uninterrupted takes in his films, pushing the boundaries of viewer patience and immersion.

Directorial Signature:

- Meta-filmic Commentary: Snow often made films about film, forcing audiences to confront the act of viewing and challenging established cinematic norms.

- Absence of Conventional Narrative: Instead of linear stories, Snow’s films were more about the experience, the play of light, sound, and image.

- Audience Challenge: Snow’s works, both in cinema and art installations, often posed challenges to the audience, demanding active engagement rather than passive consumption.

Further Reading:

Books:

- The Collected Writings of Michael Snow by Michael Snow – A collection of Snow’s writings that offers insights into his artistic approach and methodologies across various mediums.

- Michael Snow: Almost Cover to Cover by Michael Snow and Louise Dompierre – This comprehensive review of Snow’s work touches on his forays into music, sculpture, and film.

Articles and Essays:

- Michael Snow’s Experimental Films Toy with Perception and Representation by Ken Johnson, Art in America

- In Moving Images, Michael Snow Teases the Eye and the Mind by Martha Schwendener, The New York Times

- Michael Snow’s Wavelength and the Space of Dwelling by Michael Sicinski, Qui Parle

- Boundless Ontologies: Michael Snow, Wittgenstein, and the Textual Film by Justin Remes, Cinema Journal

Michael Snow – The 221st Greatest Director