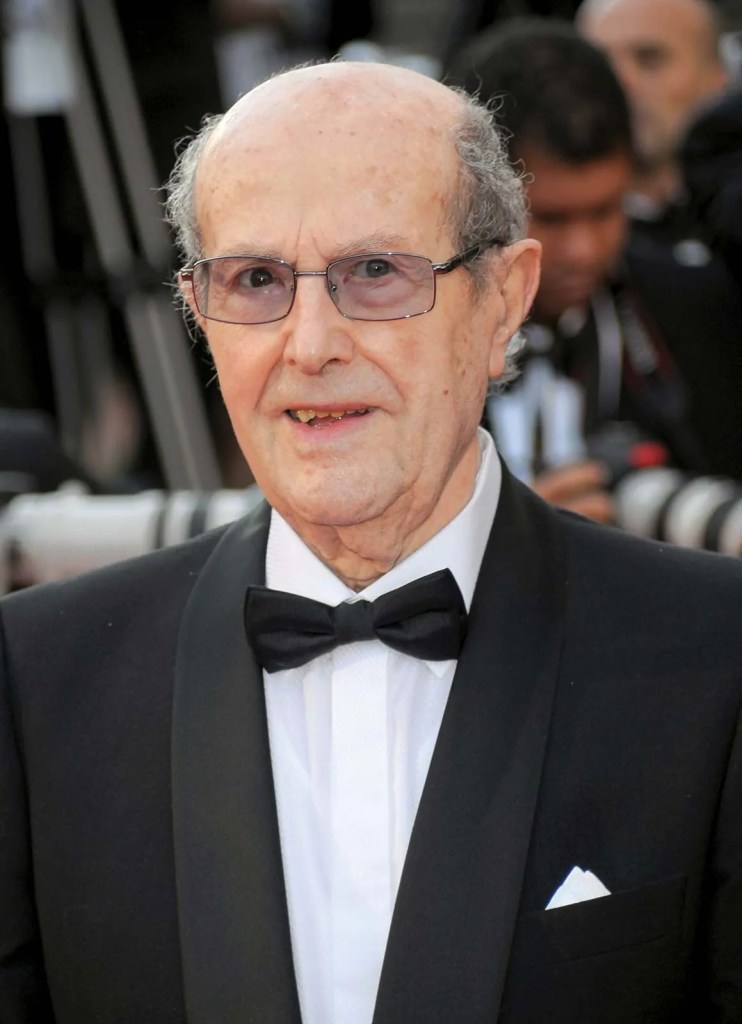

Manoel de Oliveira was a Portuguese film director and screenwriter known for his extensive and productive career that spanned over eight decades. His first film, a silent documentary titled Douro, Faina Fluvial, was released in 1931, and he remained active in filmmaking until he died in 2015 at the age of 106.

De Oliveira’s films were characterised by recurring themes of love, death, history, and the human condition. He frequently used the setting of Portugal’s Douro region as a backdrop to explore social and political issues, particularly the changes in Portuguese society throughout his lifetime. De Oliveira’s approach to filmmaking was marked by a deep commitment to realism, often using long takes and minimal editing to create a sense of continuity and authenticity. His films, such as Voyage to the Beginning of the World, grapple with existential questions and the passage of time, presenting a philosophical reflection on life and mortality.

De Oliveira’s visual style was marked by its simplicity and formal rigour. He often utilised static camera angles, long takes, and minimal camera movement, focusing on the performances of his actors and the narrative rather than visual spectacle. His compositions were often carefully arranged, using architecture and landscapes to frame his characters. This approach is evident in Belle Toujours, where the static camera and restrained editing accentuate the film’s meditative quality and the emotional depth of the characters.

What makes de Oliveira’s career special is its longevity and consistent exploration of philosophical and existential themes. Despite changing trends in cinema, he remained true to his unique style, creating deeply personal and reflective films. His commitment to exploring the human condition, his unique visual style, and his dedication to the craft of cinema made him one of the most distinctive filmmakers in the history of Portuguese cinema. His body of work, spanning from the silent era to the digital age, is a testament to his enduring vision and profound influence on Portuguese and international cinema.

Manoel de Oliveira (1908 – 2015)

Calculated Films:

- Aniki-Bobo (1942)

- Doomed Love (1978)

- Francisca (1981)

- No, or the Vain Glory of Command (1990)

- Abraham’s Valley (1993)

Similar Filmmakers

- Joao Cesar Monteiro

- Luchino Visconti

- Luis Bunuel

- Marguerite Duras

- Michael Haneke

- Miguel Gomes

- Otar Iosseliani

- Paulo Rocha

- Raul Ruiz

- Robert Bresson

- Sarunas Bartas

- Theo Angelopoulos

Manoel de Oliveira’s Top 10 Films Ranked

1. Abraham’s Valley (1993)

Genre: Drama

2. Francisca (1981)

Genre: Period Drama

3. Doomed Love (1978)

Genre: Period Drama, Romance

4. No, Or The Vain Glory of Command (1990)

Genre: Period Drama, War, Medieval

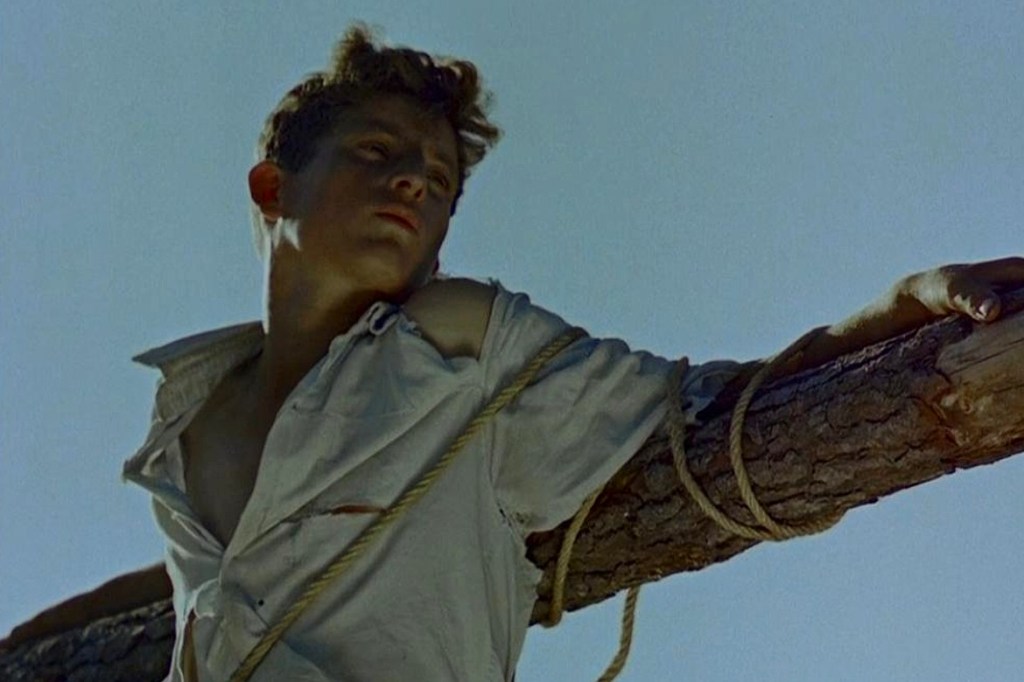

5. Acto da Primavera (1963)

Genre: Ethnofiction, Religious Film

6. Visit, or Memories (2015)

Genre: Essay Film

7. Aniki-Bobo (1942)

Genre: Drama, Family

8. Benilde of the Virgin Mother (1975)

Genre: Drama

9. The Hunt (1964)

Genre: Drama

10. The Cannibals (1988)

Genre: Operetta, Black Comedy, Period Drama

Manoel de Oliveira: The Last of the Silent Filmmakers

When The Birth of the Nation came out, Manoel de Oliviera could have gone to the cinema to see the hate-filled masterpiece that revolutionised the medium; one hundred years later, he could have bought a ticket to the crowd-pleasing Paddington. For over 100 years, Manoel de Oliviera lived cinema; towards the end of his life, for thirty or so years, he was the last living director to have made a silent film, and in an odd twist of fate, you could argue he only really got going in the later years of his life.

Born on December 11, 1908, in Porto, Portugal, Oliveira’s destiny was intertwined with the flicker of cinema’s nascent light. From his first work, 1931’s Douro, Faina Fluvial, a silent documentary, to his last, 2014’s O Velho do Restelo, Oliveira’s career was not simply enduring; it reflected a nation’s identity.

Oliveira’s upbringing was in a well-to-do industrial family. Still, he quickly gravitated towards the artistic and the profound, delving into acting and sports before a chance meeting with Italian filmmaker Rino Lupo ignited his passion for cinema. His early days behind the camera were marked by experimentation as he sought to navigate the intricate pathways of Portuguese culture and identity. The Portugal he portrayed was one of contradiction, beauty, and an indefinable longing.

With his 1942 debut feature, Aniki-Bóbó, Oliveira showcased an acute understanding of human nature and childlike innocence, a theme he would touch upon throughout his career. But success was not immediate, and Oliveira’s early works were met with confusion and, at times, contempt. His commitment to a non-commercial, deeply reflective cinema stood out in the conformist Portuguese cinema of the era.

The following decades were fraught with challenges, not least of which was political, with Oliveira’s works often clashing with the authoritarian Estado Novo regime. But the man was as steadfast as the characters he portrayed. The glacial pace, the philosophical dialogues, and the haunting imagery of his films were not merely stylistic choices; they were his voice, a voice that refused to be silenced.

It was in the 1970s that Oliveira truly blossomed following the Carnation Revolution that toppled the dictatorship. His films became bolder and more nuanced, often delving into literature, theatre, and painting. Works like Doomed Love and Francisca were not mere adaptations but reinterpretations, breathing new life into old texts.

Entering his 70s, an age when most would contemplate retirement, Oliveira embarked on an unparalleled creative journey. The films of this period were marked by fierce independence and a clarity of vision that transcended traditional narrative constraints. Whether it was The Divine Comedy‘s existential contemplation or The Convent‘s intricate family dynamics, Oliveira’s storytelling became even more deliberate and profound.

In Oliveira’s films, one could find reflections of Bergman‘s spiritual inquiries, Tarkovsky‘s poetic imagery, and even Fellini‘s sensual exuberance. But above all, one could discover Oliveira himself, an artist whose life was a ceaseless exploration of the human condition.

Oliveira’s later years were not a descent into obscurity but a grand crescendo, a triumphant affirmation of his artistic brilliance. Unlike many of his contemporaries, age did not wither him; it only enriched his vision.

Beginning with I’m Going Home, Oliveira’s films took on a more personal, reflective tone. Here was a director not merely looking at the world but gazing inward, contemplating mortality, love, and art itself. Films like A Talking Picture and The Strange Case of Angelica were imbued with a poignant longing, a bittersweet exploration of what it means to be truly alive. His films were not designed to appease or entertain momentarily; they were there to linger, provoke, and challenge.

In a nearly nine-decade career, Oliveira’s influence reached far beyond his native Portugal. Filmmakers like Pedro Almodóvar and Abbas Kiarostami hailed his genius, recognising in him a kindred spirit, a fearless explorer of cinema’s endless possibilities.

Perhaps what set Oliveira apart most was his unwillingness to conform to the trends of the time. His slow-paced and contemplative style was a stark contrast to the often frenetic, superficial filmmaking of the modern era. But in that very refusal to bend, Oliveira found a universal resonance that touched not only the mind but the soul. Even his final film, The Old Man of Belem, made when he was 106 years old, was a testament to his unyielding creativity and passion.

Manoel de Oliveira passed away on April 2, 2015, and with him went the last silent filmmaker, the last figure of a long lineage. In Oliveira’s world, cinema was not an escape from reality but a deeper engagement with it. He beckoned us to pause, reflect, and embrace the complexity and beauty of life itself.

Most Underrated Film

1981’s Francisca, one of Oliveira’s more obscure masterpieces. Based on a novel by Agustina Bessa-Luís, who often collaborated with Oliveira, Francisca is a remarkable film that explores themes of love, obsession, and the intricate societal constructs of its time.

Set in the 19th century and inspired by real-life events, Francisca tells the story of José Augusto, who becomes consumed by his infatuation with the eponymous character. The narrative unfolds not as a mere romantic tale but as a complex psychological exploration. Oliveira’s approach to storytelling in Francisca defies conventional cinematic pacing, weaving a rich tapestry that demands patience and attention from the viewer.

The film’s mise-en-scène is meticulously constructed, with Oliveira’s eye for detail shining through every frame. The costumes, the sets, and the lighting are all part of an intricate whole that evokes the essence of 19th-century Portugal. The cinematography is both elegant and restrained, mirroring the emotional containment of the characters.

Francisca is marked by Oliveira’s distinctive narrative rhythm, where dialogues often take precedence over action. Scenes unfold slowly and deliberately, allowing the audience to immerse themselves in the characters’ emotional landscape. Francisca isn’t the easiest film to watch; it’s long, slow and reflective, but you’ll get the reward if you take the risk.

Manoel de Oliveira: Themes and Style

Themes:

- Human Existence and Philosophy: Oliveira often explored existential questions about human nature, morality, love, and death. His films delve into what it means to be human, asking probing questions that linger with viewers.

- Portuguese Culture and History: Many of Oliveira’s films deeply connect with his native Portugal’s rich cultural heritage and history. He explored national identity, traditions, and societal norms.

- Literary Adaptation: Oliveira’s work is noted for its adaptations of literary works, translating complex novels and stories into visual narratives, often focusing on character psychology.

Styles:

- Slow Pacing: Oliveira’s films are known for their slow, deliberate pacing. Scenes unfold gradually, allowing the audience to fully immerse themselves in the characters’ emotional landscape.

- Theatrical Presentation: His films often have a theatrical quality, with extended dialogue scenes and a minimalist approach to action. The characters’ expressions and words are central, not the spectacle.

- Visual Aesthetic: Oliveira’s eye for detail and composition is evident in his meticulous set design, lighting, and framing. He created visually striking scenes that complement the narrative’s tone and themes.

- Complex Narratives: His films often weave intricate, multifaceted stories that explore multiple layers of character and theme. The narrative complexity is a hallmark of his work, requiring engagement and reflection from the audience.

Directorial Signature:

- Intellectual Engagement: Oliveira’s films are not meant for casual viewing; they demand intellectual engagement. He challenges his audience to think, question, and reflect, making his movies an intellectual experience as much as an emotional one.

- Uncompromising Artistic Vision: He maintained a clear and unwavering artistic vision throughout his career. Oliveira never catered to commercial trends, standing firm in his stylistic choices and thematic focus.

- Interplay of Reality and Fiction: Oliveira often blurred the lines between reality and fiction, using historical events or literary works to explore contemporary issues and timeless human dilemmas.

- Use of Recurring Actors: He frequently collaborated with the same actors, creating a sense of continuity and cohesion across different films.

- Emphasis on Dialogue: Unlike many filmmakers, Oliveira’s focus was often on the spoken word. His films are marked by rich, profound dialogues that drive the narrative, reflecting his theatrical sensibilities.

Further Reading

Books:

- Manoel de Oliveira by Randal Johnson – An in-depth examination of Oliveira’s works and his unique approach to cinema.

- The Cinema of Manoel de Oliveira by Hajnal Király – Analysis and interpretation of key films by Oliveira.

Articles and Essays:

- Oliveira, Manoel de by Wheeler Winston Dixon, Senses of Cinema

- Manoel de Oliveira and the reconciliation between theatre and cinema: forms and resources for the audiovisual preservation of theatre in his films by Francisco Javier Ruiz del Olmo & Antonio Cantos-Ceballos, Studies in European Cinema

- The Classical Modernist: Manoel de Oliveira by Jonathan Rosenbaum, Film Comment

- Game for a Century, BFI

- The Second Century of Manoel de Oliveira by Wheeler Winston Dixon, Film Quarterly

Manoel de Oliveira: The 228th Greatest Director