Kenji Mizoguchi was a Japanese filmmaker renowned for his evocative cinema, marked by social realism, visual elegance, and a deep focus on women’s lives. Drawing from traditional Japanese aesthetics, his films powerfully convey the harsh realities of early 20th-century Japan, particularly the struggles and resilience of women. With his distinctive “one-scene-one-shot” aesthetic, characterised by long takes and fluid camera movement, Mizoguchi crafted unforgettable narratives such as The Life of Oharu and Ugetsu that combine a unique aesthetic sensibility with a profound exploration of societal and economic issues.

Mizoguchi’s journey in cinema began in the silent era, and his career spanned over three decades, during which he directed about 90 films. Despite enduring a tumultuous personal life marked by early familial losses and financial hardships, he maintained an unwavering commitment to his craft. This resolve and his rich experience shaped his unique perspective and understanding of the human condition, particularly concerning societal inequities.

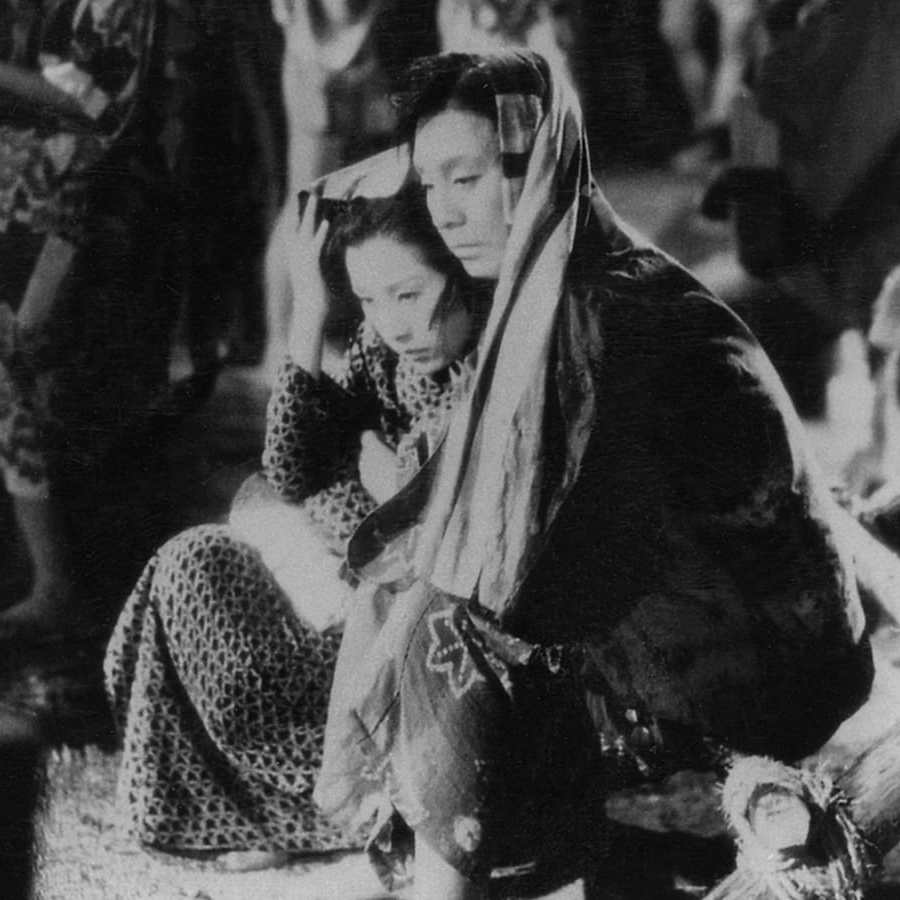

A consistent theme in Mizoguchi’s work is social realism, offering a candid depiction of the stark realities of life. He spotlighted societal and economic issues plaguing early 20th-century Japan, painting a compelling picture of the trials and tribulations of common people. Moreover, his cinema is defined by its empathetic focus on women, presenting their lives with great sensitivity. He delved into themes of sacrifice, suffering, and resilience within a patriarchal society, painting a vivid picture of their strength in the face of adversity.

One-Scene-One-Shot

Long takes and fluid camera movement define Mizoguchi’s visual style, often called the “one-scene-one-shot” aesthetic. This technique lends his films an uninterrupted sense of realism, maintaining the viewer’s emotional connection to the scene. His storytelling, deeply entrenched in tragic and melodramatic elements, encapsulates a sense of fatalism, mirroring the human experience of suffering. Additionally, his films’ visual elegance emanates from his keen aesthetic sensibility, incorporating elements such as architecture, landscape, and costumes to enhance the narrative and emotional resonance.

The influence of traditional Japanese theatre, particularly Noh and Kabuki, is profoundly evident in Mizoguchi’s films. The theatrical influence extends to his use of music, performance, and visual elements, adding to the richness of his cinematic style. His significant collaborations, notably with cinematographer Kazuo Miyagawa and actresses Kinuyo Tanaka and Machiko Kyō, were instrumental in shaping his body of work, enhancing the depth and authenticity of his storytelling.

Mizoguchi’s legacy extends far beyond Japan, with his work significantly influencing global cinema. His innovative narrative and visual techniques and his compelling portrayal of women’s lives and social issues have inspired filmmakers worldwide, including those of the French New Wave like Jean-Luc Godard and Jacques Rivette. Additionally, directors like Kaneto Shindo in Japan and Hou Hsiao-hsien in Taiwan have expressed their admiration for Mizoguchi’s work, demonstrating his enduring impact on film history. Mizoguchi remains a pioneering figure in world cinema, celebrated for his unique blend of social realism, aesthetic sophistication, and humanistic storytelling.

Kenji Mizoguchi (1898 – 1956)

Calculated Films:

- Sisters of Gion (1936)

- Osaka Elegy (1936)

- The Straits of Love and Hate (1937)

- The Story of the Last Chrysanthemum (1939)

- The 47 Ronin (1941)

- Women of the Night (1948)

- Miss Oyu (1951)

- The Life of Oharu (1952)

- Ugetsu (1953)

- A Geisha (1953)

- Sansho the Bailiff (1954)

- The Crucified Lovers (1954)

- Woman of Rumour (1954)

- Street of Shame (1956)

Similar Filmmakers

- Akira Kurosawa

- Chen Kaige

- Heinosuke Gosho

- Hiroshi Inagaki

- Hiroshi Shimizu

- Hou Hsiao-hsien

- Satyajit Ray

- Tian Zhuangzhuang

- Tomu Uchida

- Yasujiro Ozu

- Yoshitaro Nomura

- Zhang Yimou

Kenji Mizoguchi’s Top 10 Films Ranked

1. Ugetsu (1953)

Genre: Jidaigeki, Low Fantasy, Kaidan

2. Sansho the Bailiff (1954)

Genre: Jidaigeki, Tragedy

3. The Life of Oharu (1952)

Genre: Jidaigeki, Melodrama

4. The Story of the Last Chrysanthemum (1939)

Genre: Romance, Drama

5. The Crucified Lovers (1954)

Genre: Jidaigeki, Romance, Melodrama, Tragedy

6. Street of Shame (1956)

Genre: Drama

7. A Geisha (1953)

Genre: Drama

8. Miss Oyu (1951)

Genre: Melodrama, Romance

9. Sisters of Gion (1936)

Genre: Drama

10. Woman of Rumour (1954)

Genre: Drama

Kenji Mizoguchi: Themes and Style

Themes:

- Women’s plight: Mizoguchi often portrayed the challenges faced by women in Japanese society. Films like Ugetsu and The Life of Oharu showcase their suffering, sacrifices, and resilience amidst societal constraints.

- Historical narratives: Many of Mizoguchi’s works, such as Sansho the Bailiff, are set in historical contexts. These narratives shed light on sociopolitical dynamics, class struggles, and individual destinies intertwined with larger historical events.

- Social injustices: A recurring motif is the focus on social inequalities and the intricacies of the class system. Films like Osaka Elegy tackle issues related to class, corruption, and morality.

- Spirituality and the supernatural: Elements of the supernatural, often influenced by traditional Japanese folklore, are evident in movies like Ugetsu. These elements serve as metaphors for deeper human emotions and societal conditions.

Styles:

- Long takes: Mizoguchi was known for his prolonged shots that allowed scenes to unfold organically, giving audiences a more immersive experience. This technique also emphasised the actors’ performances and the mise-en-scène.

- Elevated camera angles: Many of his films feature high-angle shots, which give a bird’s-eye view of the characters and landscapes, thereby portraying a detached, observational perspective.

- Elegant mise-en-scène: He often arranged elements within a scene – characters, props, and settings – in a meticulous manner. This detailed composition contributed to the poetic and evocative ambience of his films.

- Fluid camera movements: The camera in Mizoguchi’s films often moves seamlessly, following characters or capturing the environment, creating a lyrical flow that complements the narrative’s emotional depth.

Directorial Signature:

- Female protagonists: Mizoguchi’s deep empathy for women is evident in the way he placed them at the centre of his narratives. They are not just victims but resilient fighters, reflecting the director’s critique of societal norms.

- Historical authenticity: Even when setting films in historical times, Mizoguchi ensured costumes, sets, and other details were historically accurate, reinforcing the authenticity of the narrative.

- Collaborative approach: He had a profound respect for his actors and crew, often involving them in discussions about the film’s direction. This collaborative environment enriched the storytelling process.

- Personal connection: Many of Mizoguchi’s films are believed to be influenced by personal experiences, especially the tragic events in the lives of the women close to him. This personal touch added layers of depth and sincerity to his narratives.

Kenji Mizoguchi: The 25th Greatest Director