Jonas Mekas was a Lithuanian-American filmmaker widely acknowledged as a trailblazer of American avant-garde cinema and often referred to as the “godfather of American avant-garde cinema”. He is best known for his diary-style films and relentless advocacy for independent filmmaking, including establishing the Anthology Film Archives and his influential film column in the Village Voice.

Mekas’s films are deeply personal and often revolve around his life experiences, memories, and feelings. His work often explores displacement, immigration, and the human condition, reflecting his experiences as a Lithuanian immigrant in America. His films were often diary-like, documenting his day-to-day life, the people around him, and his observations of New York City. Mekas’s work is known for its spontaneous, fragmented narrative style, reflecting his belief in cinema as a form of personal expression and exploration.

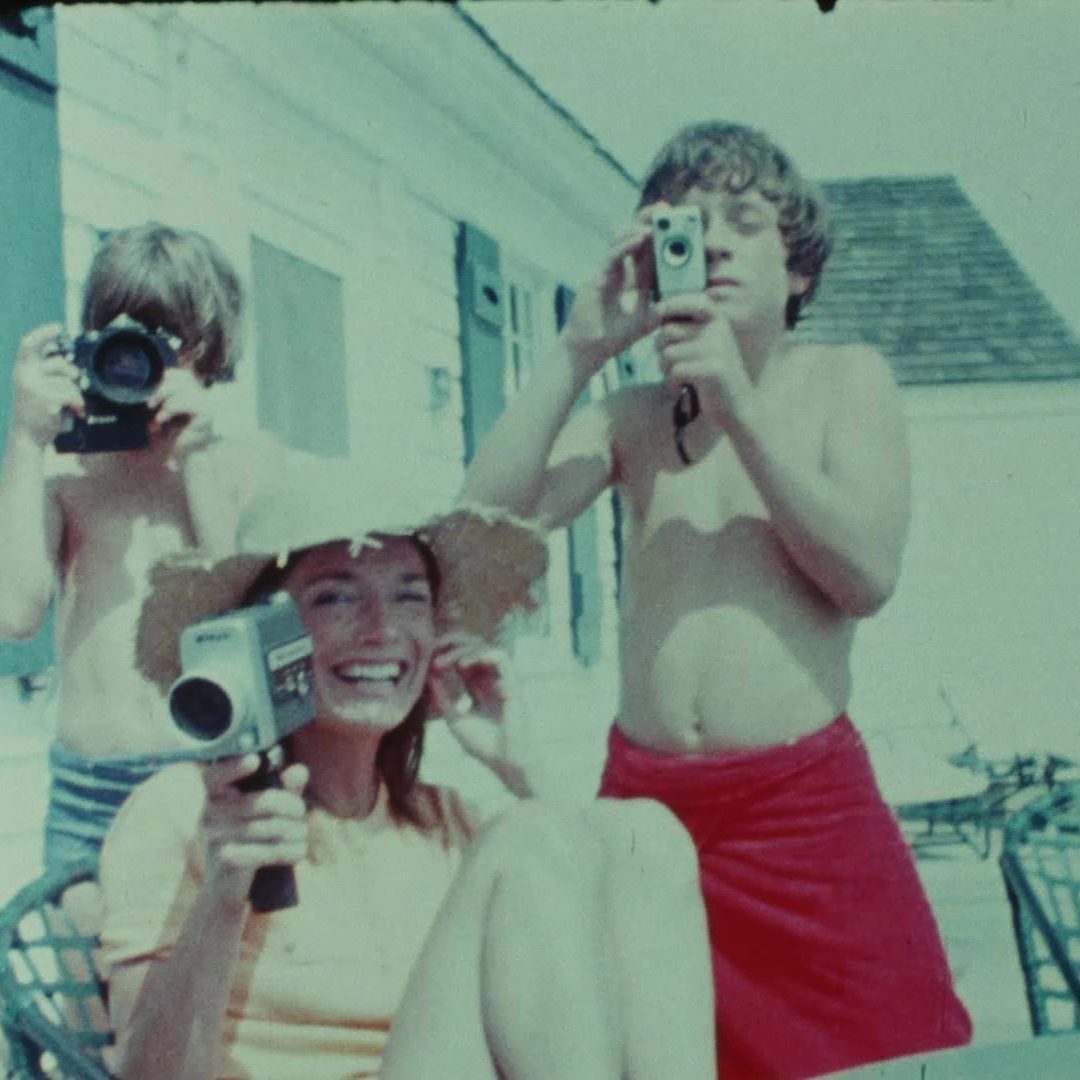

Mekas’s visual style is marked by its raw, unfiltered aesthetic. Using handheld cameras, Mekas captured his environment and experiences in an intimate, candid manner, often disregarding conventional narrative structures and techniques. His films often feature long takes, fast cuts, and overlapping soundscapes, creating a deeply immersive and visceral viewing experience. Mekas viewed cinema as a medium of personal expression, akin to writing in a diary, which resulted in an approach towards filmmaking that prioritised authenticity and emotional resonance over technical polish.

Mekas’s impact on cinema is profound as a filmmaker and an advocate for independent and avant-garde cinema. His films, with their deeply personal and unconventional style, challenged traditional cinematic conventions and inspired a new wave of filmmakers to explore cinema as a form of personal expression.

Jonas Mekas (1922 – 2019)

Calculated Films:

- Diaries, Notes, and Sketches (1969)

- Reminiscences of a Journey to Lithuania (1972)

- Lost, Lost, Lost (1976)

- As I Was Moving Ahead Occasionally, I Saw Brief Glimpses of Beauty (2000)

Similar Filmmakers

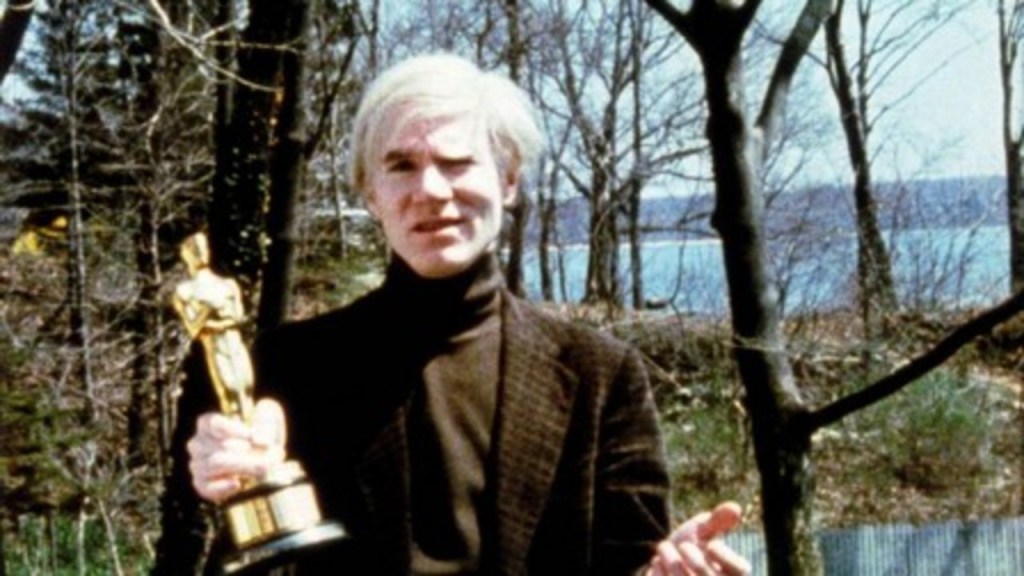

- Andy Warhol

- Bruce Conner

- Derek Jarman

- George Kuchar

- Hollis Frampton

- Jack Smith

- James Benning

- Jose Luis Guerin

- Jud Yalkut

- Ken Jacobs

- Kenneth Anger

- Maya Deren

- Michael Snow

- Peter Kubelka

- Piero Heliczer

- Robert Beavers

- Shirley Clarke

- Stan Brakhage

10 Important Jonas Mekas Films

Guns of the Tree (1961)

Genre: Drama

Diaries, Notes, and Sketches (1969)

Genre: Diary Film

Reminiscences of a Journey to Lithuania (1972)

Genre: Diary Film, Travel Documentary

Lost, Lost, Lost (1976)

Genre: Diary Film

Travel Songs (1981)

Genre: Diary Film, Travel Documentary, Experimental, Compilation Documentary

He Stands In The Desert Counting The Seconds Of His Life (1986)

Genre: Diary Film, Experimental

Scenes From The Life of Andy Warhol: Friendships & Intersections (1990)

Genre: Art Documentary, Diary Film

Song of Avignon (1998)

Genre: Diary Film

As I Was Moving Ahead Occasionally I Saw Brief Glimpses of Beauty (2000)

Genre: Diary Film

Out-Takes from the Life of a Happy Man (2012)

Genre: Diary Film

Personal Portraits: The Unfiltered World of Jonas Mekas

Hollywood dominated American moviemaking from the 1910s until the 1960s. The occasional non-Hollywood films were made, but very few reached an audience. Instead, they had to look across the sea to France, Britain, and Germany to see other experiences. However, this all changed thanks to a Lithuanian man who helped foster the American avant-garde and independent moviemaking.

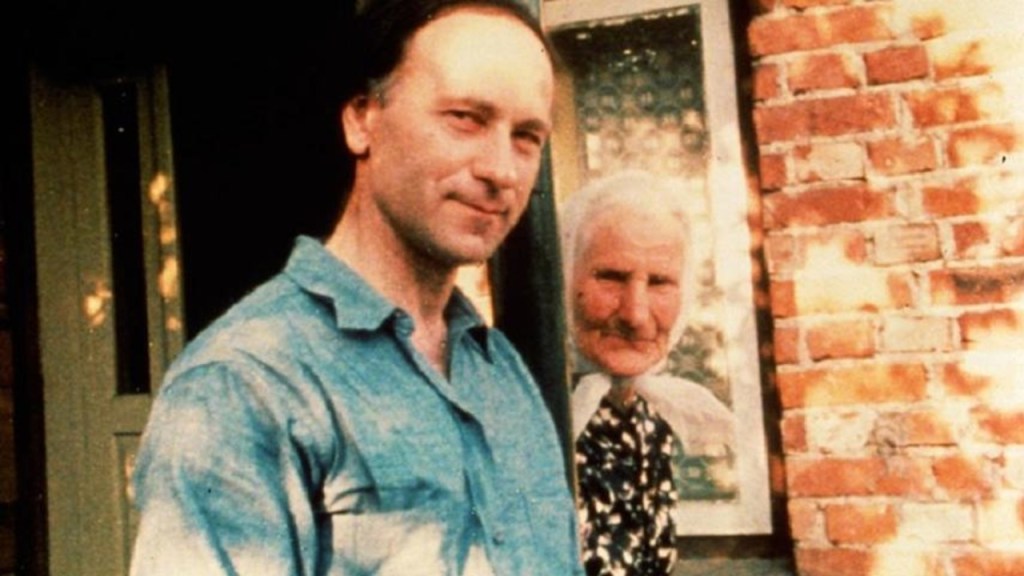

Jonas Mekas, born on December 24, 1922, in the farming village of Semeniškiai, Lithuania, was predestined for an enigmatic journey in the cinematic world. Raised amid World War II’s chaos, his early years became essential in shaping the subversive and emotionally raw style that later characterised his films.

His interest in art blossomed during these tumultuous times. However, the geopolitical situation became hazardous with Lithuania caught between Nazi Germany and Stalin’s USSR. In 1944, Jonas and his brother Adolfas Mekas were taken by the Nazis to a labour camp in Elmshorn, Germany. This separation from their country would eventually prove fortuitous, pushing Mekas away from his homeland.

Mekas, now displaced, found himself in Mainz, Germany, where he studied philosophy at the University of Mainz. 1949, the Mekas brothers immigrated to the United States, settling in Williamsburg, Brooklyn. Reminiscent of François Truffaut‘s transition from critic to filmmaker, Jonas began his career in the US as a journalist. In 1954, he co-founded “Film Culture,” an influential film magazine that became a cornerstone of independent and avant-garde cinema critique in America. Through this medium, Mekas championed the likes of Andy Warhol, John Cassavetes, and Jack Smith, placing them at the centre of the New York art scene.

The 1960s gave birth to the New American Cinema movement, which Mekas had helped foster through his support towards low-budget filmmakers. Unlike Hollywood’s studio-driven narratives, this movement was fiercely independent, experimental, and personal. Having observed cinema’s evolution from his unique vantage point as both a critic and immigrant, Mekas became one of its most vocal champions.

In 1961, Mekas, alongside Emile de Antonio and others, established the New American Cinema Group. This collective was not just about creating films; it aimed to redefine cinema, stripping away its commercial pretensions and making it a genuine reflection of personal expression. Its manifesto, fiery and radical, echoed the sentiments of the era and helped give birth to the American avant-garde film industry.

Taking cues from the poetic cinematic expressions of European masters, Mekas directed his first feature, Guns of the Trees. The film, an ode to Beat Generation angst, resonates with raw energy. Its fragmented narrative, interspersed with poetic interludes, is a testament to Mekas’ vision of cinema as a personal

As the 1960s continued, Mekas realised the importance of preserving avant-garde films. While mainstream cinema found its place in the vaults of studios, experimental films, transient in their nature, risked being lost to time. Drawing inspiration from Henri Langlois’s Cinémathèque Française, Mekas co-founded the Anthology Film Archives in 1970.

This institution, housed initially in an office on Manhattan’s Park Avenue South and later relocating to the East Village, aimed to preserve, document, and promote experimental and avant-garde films.

1969 saw Mekas unleashing Walden, also known as “Diaries, Notes, and Sketches.” Here, Mekas truly solidified the “film-diary” form, with Walden being a sprawling chronicle of his life from 1964 to 1968. In its collage of intimate and public moments, one could see shades of Chris Marker‘s La Jetée or even the reflective musings of Agnès Varda. Walden was a cinematic scrapbook, marking moments from his life and the vibrant New York avant-garde scene. It was a memory capsule crafted with love and nostalgia.

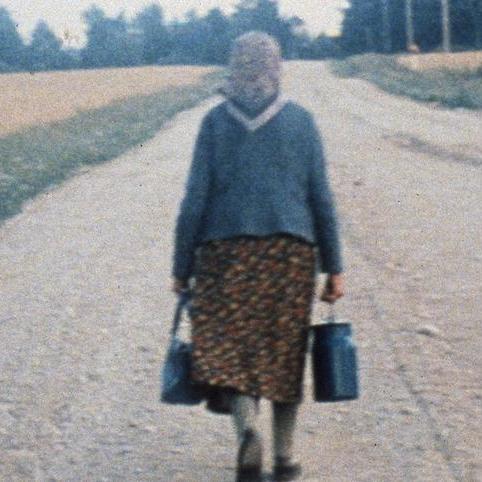

The year 1972 bore witness to another significant work from Mekas, Reminiscences of a Journey to Lithuania. The film was a poignant return to his homeland, a meditation on displacement, identity, and memory. With its fragmented style, reminiscent of T.S. Eliot’s modernist poetry, Mekas navigated the treacherous waters of his past, reconciling the pain of war and the bittersweetness of nostalgia.

Picking up from the emotional threads of his previous work, Mekas’ 1976 film Lost, Lost, Lost was a continuation of his cinematic diary, chronicling his early years in New York. In this piece, the feeling of displacement is even more palpable. He captures the immigrant experience with its dichotomies of excitement and alienation, discovery and loss. Mekas’ camera becomes an extension of his soul, recording fragments of a world both new and intimidating.

Mekas’ magnum opus, the 2000 film As I Was Moving Ahead Occasionally I Saw Brief Glimpses of Beauty, is a testament to his life’s philosophy. This five-hour-long epic is an emotional tour de force, presenting fleeting moments of joy, sorrow, love, and wonder from Mekas’ life. As the title suggests, it’s a journey where the mundane becomes magical, where every moment holds the promise of revelation. T

Even in his later years, Mekas remained indefatigable. He embraced the digital age, creating films and projects well into the 21st century. From short videos to his 365 Day Project, where he released a short movie daily for a year, Mekas continued pushing cinematic boundaries. Often distributed online, these later works reflected a world in flux, proving that Mekas never left the cutting edge.

The world of movies would be vastly different without Jonas Mekas. His influence extends beyond just his films. Mekas created a space for alternative cinema through his writings, the Anthology Film Archives, and his sheer presence in the New York art scene. He championed a kind of filmmaking that was personal, raw, and devoid of commercial constraints.

Filmmakers like Jim Jarmusch, Harmony Korine, and even the enigmatic Terrence Malick owe a debt to Mekas’ vision and ethos. But more than that, his films stand as a beacon for anyone who believes in the power of personal storytelling. In an age of blockbusters and high-budget spectacles, Mekas’ work is a gentle reminder that cinema, at its core, is about capturing the human experience in all its messy, beautiful, transient glory.

Most Underrated Film

Although it is widely considered his best film, As I Was Moving Ahead Occasionally I Saw Brief Glimpses of Beauty remains criminally under-watched. The film’s production is nothing short of ambitious. Culled from nearly 30 years of Mekas’ personal footage, its five-hour-long narrative transcends conventional storytelling. Instead, it delves into a poetic exploration of Mekas’ own existence. The film’s title encapsulates its essence: Every ordinary moment holds the potential of extraordinary beauty.

It’s the epitome of a Mekas film. It is the culmination of all his life’s work and comes together beautifully. When I think of the film, I remember the mesmerising sequences of Mekas’ children growing up, the tranquil beauty of winter scenes, and the intimate moments of joy, love, and discovery. Each scene, irrespective of its content, is imbued with a profound sense of intimacy and emotional depth, quintessentially Mekas.

Compared to his broader work, As I Was Moving Ahead… is arguably Mekas’ most personal endeavour. Where films like Walden captured the zeitgeist of the New York avant-garde scene, this piece is Mekas stripped bare, presenting life as he saw and felt it.

Jonas Mekas: Themes and Style

Themes

- Personal Exploration: Mekas’ works, especially his film diaries, delve deeply into his experiences, from his days in war-torn Lithuania to his immigrant life in New York. His cinema is often a mirror to his soul.

- Displacement and Alienation: Being an immigrant, themes of displacement, homesickness, and the search for identity in a foreign land recur throughout his films.

- Ephemeral Nature of Life: The fleetingness of moments, memories, and emotions is a consistent theme, with Mekas attempting to capture life’s transient beauty.

- Raw Human Emotion: Mekas never shied away from showcasing raw emotions—be it joy, sorrow, love, or wonder. His films are a testament to the human experience in its purest form.

Styles

- Film-diary Format: Mekas pioneered the “film-diary” form, where he chronicled his daily life and experiences, turning ordinary moments into extraordinary cinematic sequences.

- Fragmented Narrative: Eschewing traditional linear narratives, Mekas’ films often feature a fragmented, non-linear structure, mimicking the way memories come to us.

- Raw Aesthetics: His films, especially the early ones, have a rough, almost unpolished feel, emphasising authenticity over technical perfection.

- Intimate Cinematography: Close-up shots, handheld camera movements, and a focus on intimate moments became staples in Mekas’ filmography, bringing the viewer closer to the subject.

- Collage Technique: Mekas often used a collage technique, piecing together different footage, resulting in a kaleidoscopic view of life.

Directorial Signature

- Authenticity Over Perfection: Mekas valued authenticity. His films feel genuine, with little concern for the polished aesthetics of mainstream cinema.

- Emphasis on the Ordinary: Mekas found beauty in the mundane. Whether it’s a scene of snow falling or children playing, he magnified life’s ordinary moments, turning them into profound cinematic experiences.

Further Reading:

Books:

- I Had Nowhere to Go by Jonas Mekas – This autobiographical work captures Mekas’s early life, his experiences as a displaced person during and after WWII, and his eventual migration to New York City.

- Scrapbook of the Sixties: Writings 1954-2010 by Jonas Mekas – A compilation of Mekas’s writings that provides insights into his perspectives on cinema and the arts.

Articles and Essays:

- To Free the Cinema: Jonas Mekas and the New York Underground by David E. James, Princeton University Press

- The Avant-Garde Filmmaker Who Tried to Tell the Truth by Will Heinrich, The New York Times

- The Eternal Exile: On Jonas Mekas’s Cinema of Memory and Displacement by Dante A. Ciampaglia, LA Review of Books

- Jonas Mekas: How a Lithuanian Refugee Redefined American Cinema by John Patterson, The Guardian

- My Debt to Jonas Mekas by J. Hoberman, The New Yorker

- Mekas, Jonas by Genevieve Yue, Senses of Cinema

Documentaries:

- Jonas in the Desert (1994) – A documentary by Peter Sempel that offers an intimate look into Mekas’s life, work, and relationships with other artists and filmmakers.

Jonas Mekas: The 214th Greatest Director