John Huston, one of the great auteurs of American cinema, is celebrated for his storytelling mastery, eclectic filmography, and ability to draw out iconic performances from his actors. His distinctive style, marked by narrative complexity and a keen sense for realistic portrayal of life, helped him create some of the most memorable films in Hollywood history. Best known for influential works like The Maltese Falcon and The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, Huston left his mark on various genres, from noir to adventure to dark comedy.

Born into a show business family, Huston started his career as a screenwriter before moving on to directing. His directorial debut, The Maltese Falcon, became an instant classic, establishing him as a formidable storyteller with an instinct for complex plots and rich character development. His subsequent career, spanning over four decades, saw him dabbling in diverse genres and themes, maintaining a steady reputation from the start of his career in the 1940s till its end in the 1980s.

Huston’s films are often noted for their complex narratives and psychologically rich characters. Films like Fat City and Under the Volcano delve deep into their protagonists’ motivations, flaws, and moral dilemmas, adding layers of depth to the storytelling. Huston’s penchant for literary adaptations, including The Maltese Falcon and The Dead, showcased his ability to bring literature to life on screen, faithfully capturing the essence of the source material while making it accessible to a wider audience.

Hollywood’s Hemingway

The realism in Huston’s films set him apart from many of his contemporaries. Drawing from his war experience and a desire for authenticity, he portrayed characters and scenarios with a grittiness that was a departure from typical Hollywood glamorisation. This can be seen in films like The Asphalt Jungle, where criminals are depicted as ordinary people rather than glamorous outlaws. His visual style also complemented his realistic approach to storytelling, with the use of shadow and composition in The Maltese Falcon setting the visual template for film noir.

Huston’s collaborative approach with actors is another hallmark of his filmmaking. His films featured many performances from some of the biggest stars of the time, including several collaborations with Humphrey Bogart, resulting in some of the actor’s most memorable roles. This demonstrated his knack for drawing out nuanced performances and his ability to work effectively with his cast.

John Huston’s legacy extends beyond his impressive filmography. He influenced many future filmmakers throughout his career, and his work continues to be studied and admired. Directors like Martin Scorsese, The Coen Brothers, and Guillermo del Toro have all cited Huston as an influence.

John Huston (1906 – 1987)

Calculated Films:

- The Maltese Falcon (1941)

- Let There Be Light (1946)

- The Treasure of the Sierra Madre (1948)

- Key Largo (1948)

- The Asphalt Jungle (1950)

- The African Queen (1951)

- The Night of the Iguana (1964)

- Fat City (1972)

- The Man Who Would Be King (1975)

- The Dead (1987)

Similar Filmmakers

John Huston’s Top 10 Films Ranked

1. The Treasure of the Sierra Madre (1948)

Genre: Adventure, Drama, Neo-Western

2. The Maltese Falcon (1941)

Genre: Film Noir, Mystery, Crime

3. The Asphalt Jungle (1950)

Genre: Heist Film, Film Noir

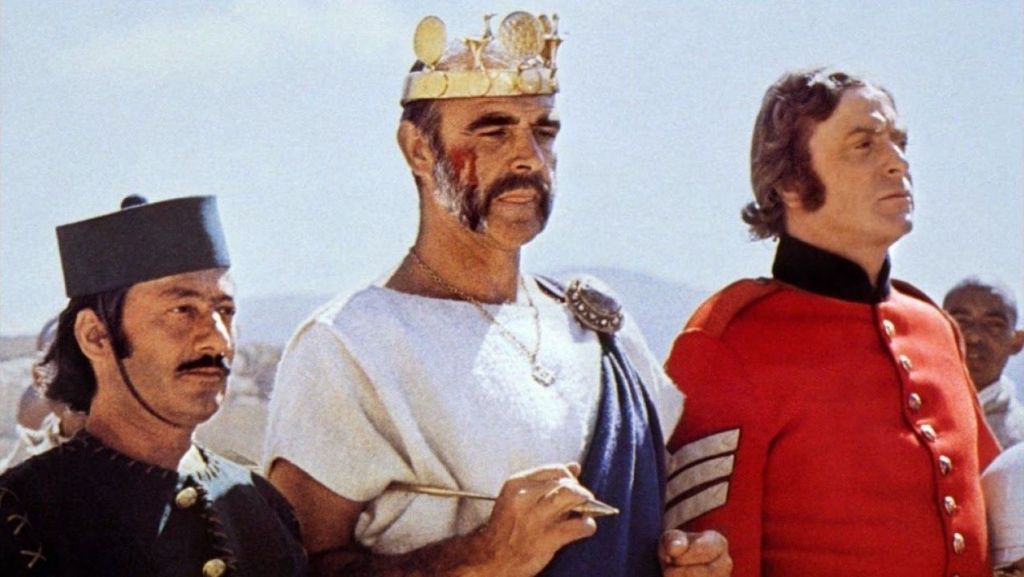

4. The Man Who Would Be King (1975)

Genre: Adventure, Buddy, Comedy, Period Drama

5. The African Queen (1951)

Genre: Adventure, Romance

6. Fat City (1972)

Genre: Drama, Sports

7. The Night of the Iguana (1964)

Genre: Psychological Drama, Drama

8. The Dead (1987)

Genre: Drama, Slice of Life

9. Key Largo (1948)

Genre: Gangster Film, Thriller, Film Noir

10. The Misfits (1961)

Genre: Drama, Neo-Western, Romance

John Huston: Cinema’s Hemingway

Never predictable, always erratic, John Huston was one of the longest-lasting of the classic Hollywood directors. He was raised in showbiz; his father, Walter Huston, was a revered actor. Despite this theatrical lineage, young Huston’s beginnings were anything but linear. His adolescence was marked by various pursuits—boxing, painting, and acting, to name a few. But it seemed the pull of cinema was too much for the bull-headed boy.

As the 1930s rolled in, Hollywood was in the throes of the golden age. And Huston, with his love of storytelling and familiar connections, found himself in a great position to take advantage of this era. Writing for titans like William Wyler, Howard Hawks, and Raoul Walsh, Huston honed his craft, understanding the intricate ballet of characters and plot. With each screenplay, whether it was the poignant drama of Jezebel for Wyler or the kinetic energy of High Sierra for Walsh, Huston displayed an uncanny ability to breathe life into celluloid.

Yet, it was 1941’s The Maltese Falcon that catapulted Huston from a writer to something more. Taking the directorial helm for the first time, he painted a noir masterpiece, a dark tale where shadows, whispered secrets and characters were draped in shades of moral ambiguity. It was the first gunshot of the Film Noir era and when Huston declared himself.

This film had everything the great Huston flicks to come would embody: a captivating narrative that wove together suspense and intrigue, a visual style that played with light and darkness to mirror the complexities of the human psyche and a knack for extracting stellar performances from his ensemble cast.

But as Huston’s star rose in Hollywood, the world outside was in turmoil. The echo of war drums was becoming deafening, and by 1942, America was enmeshed in the cataclysmic frenzy of World War II. Instead of basking in the newfound glory, Huston donned a new role, a Lieutenant in the U.S. Army Signal Corps. Commissioned to create films for the Army, Huston chronicled the stark realities of warfare, producing documentaries like Report from the Aleutians and San Pietro, which, in their unvarnished authenticity, captured the grim world at war.

The post-war years heralded a return to Hollywood, but Huston was not the same. The war had etched its marks on him, giving his subsequent works an edge. And in 1948, this newfound depth found its most brilliant expression in The Treasure of the Sierra Madre. A tale of gold, greed, and the human soul, the film was more than just a cinematic venture. It was a spiritual exploration, a dive into the murky waters of human desire and decay. Casting his father, Walter Huston, in an Oscar-winning role, created the toughest film of Hollywood’s golden age.

In the same year, Huston created 1948’s Key Largo, which emerged as a brooding meditation on the ghosts of war and the intricate dance of morality. Setting his tale against the backdrop of a hurricane-lashed hotel, Huston wove a suspenseful drama where Humphrey Bogart and Edward G. Robinson’s characters clashed in a stormy ballet of wills.

But the director’s gift lay in his ability to transition seamlessly between diverse narratives. From the psychological tension of Key Largo, he delved into the neon-lit alleys of crime with The Asphalt Jungle. This incredible film noir dealt with ambition, betrayal and the fragile nature of human alliances. While he briefly traversed the battlefields again with The Red Badge of Courage, it was clear that Huston’s primary interest lay in the shades of human character.

Then, in 1951, the world witnessed Huston’s craftsmanship ascend to new echelons with The African Queen. Casting the indomitable duo of Humphrey Bogart and Katharine Hepburn, Huston’s venture into the African wilderness was an audacious blend of adventure and romance, resilience and redemption. But more than the story itself, the making of The African Queen became legendary: battling treacherous terrains, malarial fevers, and logistical nightmares, Huston’s undying spirit proved capable of conquering nature itself.

However, just as Huston was really getting going, America’s political landscape was undergoing seismic shifts. The House Committee on Un-American Activities was casting its long, McCarthyist shadows on Hollywood, and Huston, with his proclivity for justice and freedom, found himself amidst the whirlwind. He was vehemently opposed to the witch hunts, and his political and personal stances led him to be involved in the proceedings, which would impact his ability to produce films.

The tumultuous 1950s saw Huston experimenting with his narrative styles, moving away from the raw realism of his previous ventures. Moulin Rouge was a visually sumptuous biographical melodrama, which might lack narrative strength but makes up for it with its vibrant images of the life of artist Toulouse-Lautrec. It departed from his previous work, infused with colour, music, and a bohemian zest for life.

Beat the Devil followed an eccentric caper with shades of noir and comedy. It was Huston playing with genres and audience expectations. It’s a lesser Bogart-Huston collaboration, but it’s still worth a watch. However, most of this decade was spent making films that were never quite the sum of their parts. Perhaps there is no better example than his adaptation of Moby Dick in 1956, which feels like the perfect Huston film. The movie is good, but it never quite gets going.

John Huston was an awkwardly consistent director. Not every film was good, but sure enough, every now and then, he would make a great film. It’s often said that he did one movie for the money and then one for himself.

One he did for himself was 1961’s The Misfits, a raw, emotional masterpiece. The iconic playwright Arthur Miller wrote the story, a poignant exploration of love, loneliness, and the inexorable march of time. But what added gravitas to the film was its star-studded cast: Clark Gable, Marilyn Monroe, and Montgomery Clift—each battling their demons—lent a heart-wrenching authenticity to their roles. Tragically, the film would be the final curtain for both Monroe and Gable, embedding The Misfits in cinematic lore as a haunting swan song.

Huston’s thematic explorations continued to evolve with The Night of the Iguana in 1964. Adapting Tennessee Williams’ play, Huston delved into spiritual and sexual despair. Set against the sultry backdrop of a Mexican hotel, the film was a tempestuous dance of desires, of characters shackled by their pasts, yearning for redemption. Richard Burton’s portrayal of the tormented Reverend Shannon showcased Huston’s ability to extract performances that were at once visceral and vulnerable.

However, Huston would take a significant stumble in the mid-60s when he decided to take on the impossible task of adapting the Book of Genesis in The Bible: In The Beginning. It’s not a very good film. It’s pretty dull, but there are glimpses of classic Huston here. Ultimately, though the career marked a turning point in Huston’s career, he became less prolific and turned towards acting rather than directing.

Returning to the underbelly of urban America in the 1970s, Fat City emerged as a gritty, unvarnished portrayal of the boxing world. It was Huston revisiting familiar terrains, echoing shades of his early adventures. But this was a more mature, contemplative Huston, shedding light on his characters’ shattered dreams and desolation. In its rawness, Fat City showcased the beauty that lay in the broken and the beaten.

While best known as a director, it’s worth mentioning that Huston also carved a niche for himself in front of the camera, especially towards the latter half of his career. With roles in films like Chinatown and The Cardinal, Huston demonstrated a palpable screen presence, embodying characters with an aura that was at once intimidating and magnetic.

1975 heralded the release of The Man Who Would Be King, a film that seemed to encapsulate the essence of Huston’s cinematic philosophy. Based on Rudyard Kipling’s novella, it was an epic tale of ambition, brotherhood, and the perilous allure of power. It was vintage Huston – a harmonious blend of the external and the internal, the spectacular and the subtle.

Even though he was at this point in his 70s, he continued to make brilliant films like Wise Blood. Delving into the surreal and the spiritual, this adaptation of Flannery O’Connor’s novel was a deep dive into the American South’s religious eccentricities. Under the Volcano was another passion project. Chronicling the final hours of a self-destructive British consul, the film was a haunting portrayal of alcoholism, desolation, and the inescapable spectres of the past. Albert Finney’s performance, under Huston’s guidance, was a masterclass.

As the twilight of his career approached, Huston made one final film: The Dead. A 1987 adaptation of James Joyce’s short story, the film was a lyrical exploration of love, memories, and the inexorable passage of time. It was a fitting conclusion to Huston’s directorial journey.

On August 28, 1987, the world bid adieu to this cinematic titan. But his legend has continued since. Filmmakers like Martin Scorsese, Francis Ford Coppola, and the Coen Brothers have cited him as an influence or the maker of their favourite films. He might be gone, but John Huston was anything but forgettable.

Most Underrated Film

So, what’s his most underrated film? Is it a forgotten work of the 50s? Perhaps Heaven Knows, Mr Allison? No. In my opinion, it’s The Night of the Iguana. Adapted from Tennessee Williams’ play, the film, set in the steamy backdrop of Mexico, delves into themes of isolation, redemption, and human vulnerabilities.

The production was as tumultuous as the narrative itself. Shot on location in Mexico, Huston battled the elements, and reports of off-screen tensions among the cast, particularly between Richard Burton and Ava Gardner, became as legendary as the film itself. But, in true Huston fashion, he harnessed this raw energy, translating it into a movie pulsating with emotional intensity. It’s an odd film, never feeling very ‘classic Hollywood.’ It’s slower-paced, melodramatic and morally ambiguous. It’s a brilliant, immersive film that presents characters on the brink—of sanity, morality, and existence.

It’s not got the thrills of Huston’s noirs, but this little film remains an incredibly gripping and enthralling watch.

John Huston: Themes and Style

Themes:

- Human Vulnerability and Flawed Characters: Huston often presented characters grappling with their demons, be it through greed, as in The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, or moral degradation in The Asphalt Jungle. His protagonists were rarely conventional heroes; instead, they were deeply flawed individuals searching for redemption or self-understanding.

- Morality and Ethics: Films like The Maltese Falcon question the boundaries of right and wrong. Huston delved into moral ambiguities, illustrating the grey areas in which most human experiences reside.

- Adventure and Human Ambition: Many of his films, such as The Man Who Would Be King, portray grand adventures, illustrating both the grandeur of human ambition and its inherent pitfalls.

- Nature vs. Man: Whether it’s the gold-laden landscapes of The Treasure of the Sierra Madre or the daunting backdrop of The African Queen, nature frequently serves as a character in itself, sometimes indifferent and, at other times, antagonistic to human endeavours.

Styles:

- Location Shooting: Huston often shunned studios for real locations. This added authenticity to the narrative and intensified the story’s atmospheric tension. For instance, The Night of the Iguana was shot in the heat of Mexico, which added a tangible layer of discomfort and urgency to the film.

- Adaptation of Literary Works: Many of Huston’s most acclaimed films, like The Maltese Falcon or The Dead, were adaptations of literary works.

- Deep Character Study: Huston’s films often linger on characters, delving deeply into their psyches. This is evident in movies like Fat City, where the lives and struggles of boxers are portrayed in raw, unflinching detail.

- Naturalistic Dialogue: His characters often spoke in a manner reflecting real conversations, punctuated with imperfections and moments of introspection.

Directorial Signature:

- Evolving Yet Consistent Vision: While Huston’s style changed over his long career, there was consistency in his exploration of human nature and his portrayal of life’s inherent complexities.

- Collaboration with A-list Actors: Huston had a knack for drawing out sterling performances from his cast. His collaborations with stars like Humphrey Bogart, Katharine Hepburn, and Sean Connery resulted in some of cinema’s most memorable moments.

- Cinematic Realism: Even in his most commercial ventures, there was a grounding in reality. His characters, dialogues, and settings all bore a sense of authenticity.

- Multi-dimensional Storytelling: While the primary narrative was evident, Huston often wove in multiple subplots and character arcs, providing a rich tapestry for viewers to engage with.

Further Reading:

Books:

- John Huston: Courage and Art by Jeffrey Meyers – A comprehensive biography that explores Huston’s life, his relationships, and the stories behind the making of his legendary films.

- An Open Book by John Huston – An autobiography where Huston himself recounts his experiences in Hollywood and the film industry.

Articles and Essays:

- Huston, John by Bruce Jackson, Senses of Cinema

- John Huston’s Glorious Losers by Terry Teachout, Commentary Magazine

- John Huston: A Look at His Influence by Kristin M. Jones, The Wall Street Journal

Documentaries:

John Huston: The Man, the Movies, the Maverick (1988) – This documentary delves into the life and works of Huston with interviews and behind-the-scenes footage.

John Huston: The 38th Greatest Director