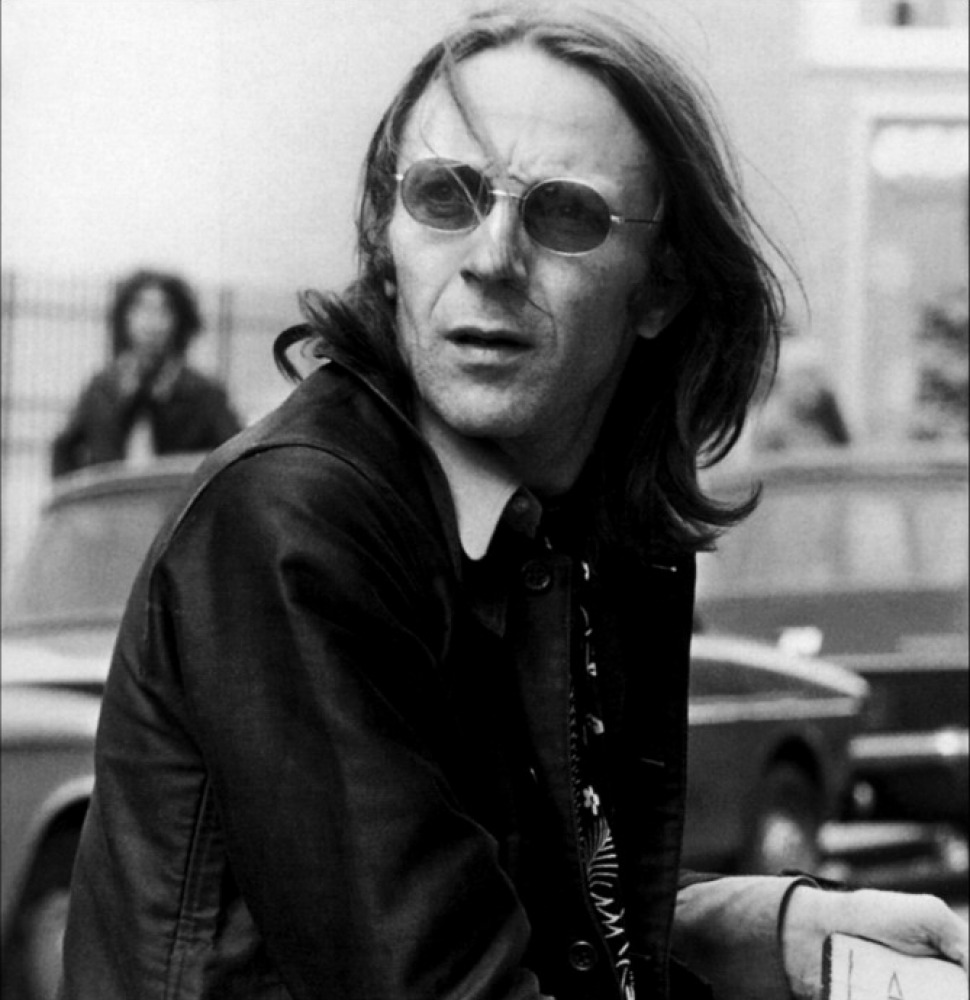

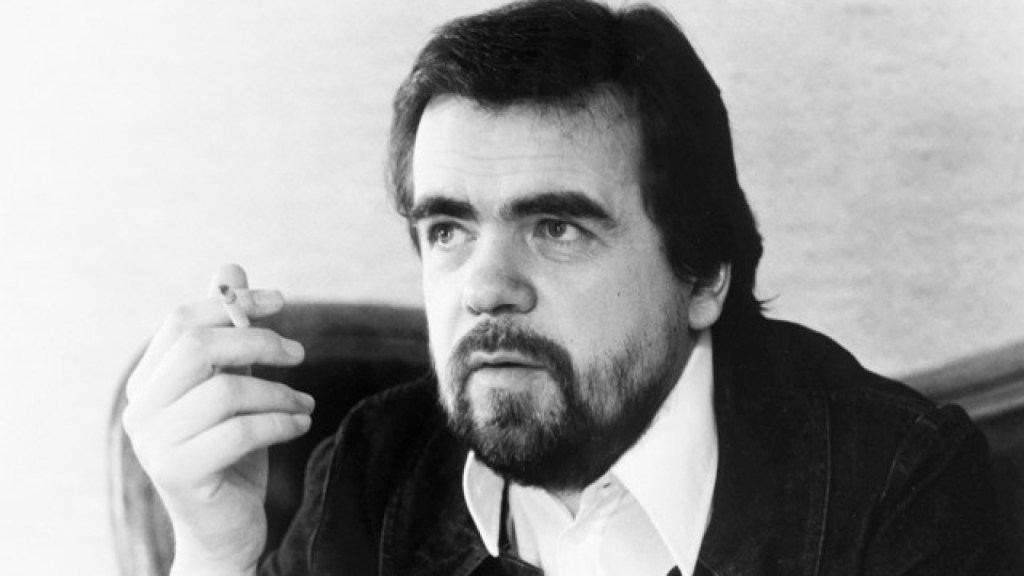

Jean Eustache, a highly respected yet enigmatic figure in French cinema, is best known for his landmark film, The Mother and the Whore. His work, while limited due to his untimely death, remains influential in art cinema, renowned for its potent mix of realism and introspection.

Eustache’s films are characterised by an intense focus on ordinary people and their day-to-day lives. His background, growing up in rural France before moving to Paris, significantly influenced his filmmaking. This is evident in his short film, Le Père Noël a les yeux bleus (Santa Claus Has Blue Eyes), which centres around a young man in provincial France, a motif Eustache would often revisit.

Eustache’s filmmaking approach was unique and innovative. He had a distinct narrative style that avoided traditional storytelling. This is vividly demonstrated in The Mother and the Whore, a three-and-a-half-hour exploration of a love triangle that hinges on conversational sequences, probing the emotional complexities of modern relationships. Despite its length and seemingly mundane premise, the film is celebrated for its raw and brutally honest depiction of post-May ’68 disillusionment.

The Aftermath of the French New Wave

Visually, Eustache’s style is understated yet impactful. His unobtrusive cinematography and minimalist aesthetics allow the narrative to take centre stage. This visual philosophy can be seen in Numéro Zéro, where Eustache utilises found footage and archival interviews to construct an intimate portrait of his grandmother, reflecting a unique, personal approach to the documentary genre.

Though his career was tragically brief, Eustache’s influence is far-reaching. Directors like Arnaud Desplechin and Olivier Assayas have cited him as a significant influence. His pioneering exploration of realism and complex character-focused narratives have left an indelible mark on international cinema, inspiring filmmakers to pursue similar themes. Despite the initial mixed reception of some of his films, Eustache’s work has undergone a significant critical reevaluation and is now recognised for its groundbreaking contribution to cinema.

Jean Eustache (1938 – 1981)

Calculated Films:

- The Mother and the Whore (1973)

- My Little Loves (1974)

Similar Filmmakers

- Arnaud Desplechin

- Benoit Jacquot

- Bertrand Tavernier

- Catherine Breillat

- Claire Denis

- Eric Rohmer

- Eugene Green

- Jacques Rivette

- Jacques Rozier

- Jean-Luc Godard

- Jean-Paul Civeyrac

- John Cassavetes

- Luc Moullet

- Marcel Pagnol

- Maurice Pialat

- Olivier Assayas

- Pedro Costa

- Philippe Garrel

Jean Eustache’s Films Ranked

1. The Mother and the Whore (1973)

Genre: Drama, Romance

2. My Little Loves (1974)

Genre: Drama, Coming-of-Age

3. Numero Zero (1971)

Genre: Documentary

4. A Dirty Story (1977)

Genre: Essay Film, Drama

5. The Virgin of Pessac (1968/1979)

Genre: Direct Cinema, Ethnographic Film

Jean Eustache: The Man Who Broke the Myth of the French New Wave

Born in Pessac, near Bordeaux, Jean Eustache grew up in the rural countryside of France, in a setting that would later serve as the backdrop for his autobiographical pieces. These formative years in the rustic charm of provincial France would deeply influence his storytelling, anchoring the core of his narratives in authentic, human experiences.

From a young age, Eustache displayed an insatiable curiosity for the arts. In his teenage years, he moved to Paris, a decision that would prove pivotal for his career. The city, then a buzzing hive of revolutionary ideas, artistic expression, and social change, provided the budding director with fertile ground to plant his cinematic roots.

Upon his arrival in Paris, Eustache quickly found himself amidst the luminaries of the French New Wave — a cinematic movement characterized by its break from traditional filmmaking conventions in favour of a more experimental, freewheeling approach. While he was never formally associated with the core members of the New Wave, the likes of Jean-Luc Godard, François Truffaut, and Claude Chabrol, Eustache’s early works undeniably carried the mark of the movement.

Drawing inspiration from the New Wave’s preference for location shooting, improvisational acting, and a direct confrontation of social norms, Eustache’s films began to explore the depth of human relationships and societal structures. Yet, where many of the New Wave directors employed stylistic flourishes, Eustache grounded his work in a raw, almost voyeuristic realism, often blurring the line between documentary and fiction.

Released in 1973, The Mother and the Whore is perhaps Eustache’s most celebrated and contentious work. This three-and-a-half-hour magnum opus delves into the intricate web of relationships in post-May ’68 Paris, presenting an unfiltered portrayal of love, lust, and longing. The film orbits around Alexandre, a young intellectual caught in a tumultuous love triangle with his girlfriend, Marie and a nurse, Veronika. Through extensive monologues and dialogues, the characters dissect their feelings, philosophies, and insecurities.

While praised for its audacity and depth, The Mother and the Whore was not immune to criticisms. Some hailed it as a definitive exploration of the human condition, while others saw it as a self-indulgent exercise. Yet, what is undeniable is the film’s impact; it remains a watershed moment in French cinema, effectively capturing the zeitgeist of a generation caught between revolutionary ideals and the looming shadow of modernity.

A thread that weaves throughout Eustache’s oeuvre is his penchant for the autobiographical. His films often mirror his own experiences, using the medium as a cathartic release of personal memories and emotions.

This autobiographical approach provided his films with intimacy and authenticity, allowing audiences to resonate with the characters and their experiences. For many, it’s this genuine connection that elevated Eustache from merely being a filmmaker to an artist who painted the canvas of cinema with the hues of his own life.

1974 saw the release of My Little Loves, a film that further showcased Eustache’s proficiency in sculpting intimate narratives. A semi-autobiographical recount of a boy’s adolescence in post-war France of the 1950s, My Little Loves melds the realities of growing up in a working-class family with the universal trials of coming-of-age. Through the eyes of Daniel, the protagonist, Eustache, tenderly portrays the moments of innocence, wonder, and heartbreak that punctuate youth. The subtly unfolding film offered a stark contrast to the more dynamic and turbulent atmospheres of his contemporaries’ works, emphasizing Eustache’s signature style of subdued realism.

It would be remiss not to note that while distinctly modern, Eustache’s voice was paradoxically more conservative than many of his contemporaries. While the French New Wave revelled in breaking societal and cinematic conventions, Eustache’s stance leaned more reactionary, often harking back to traditional values and structures. His films, although raw and confrontational in content, evoked a longing for simpler times.

Eustache’s oeuvre is punctuated by a penchant for revisiting themes and narratives. This is most evident in works such as A Dirty Story and La Rosière de Pessac. The former is a fascinating diptych featuring two versions of the same story — one as a fictional recounting and the other as a documentary-style interview. The dual narratives explore voyeurism and human psychology, challenging the audience’s perception of reality and fiction.

La Rosière de Pessac exemplifies Eustache’s fondness for serial works. Shot in 1968 and then again in 1979, the film documents an annual village ceremony where a girl is crowned for her virtue. The decade-long gap between the two films provides a captivating look at the shifts in societal values and norms, further underscoring Eustache’s fascination with tradition and its interplay with modernity.

Jean Eustache committed suicide in 1981, leaving behind an impactful yet limited filmography. Although many of his contemporaries might have gotten more immediate recognition, Eustache’s legacy has grown and matured over time. His meticulous approach to narrative, his blurring of fiction and documentary, and his raw, unapologetic examination of human relationships have inspired many filmmakers across generations. Many modern directors cite him as a touchstone, recognizing his unique voice and the timeless nature of his works.

Most Underrated Film

The Mother and the Whore is and will always be the most talked about Jean Eustache film, and rightfully so. He left behind such a small filmography that, frankly, there’s not much to investigate. His non-feature films don’t get much of a look in, so they are under-watched, but My Little Loves is the most underrated.

Produced in 1974, the film chronicles the tender journey of Daniel, a boy navigating the pangs of adolescence in post-war France. The production, steeped in a muted palette and deliberate pacing, mirrors its protagonist’s restrained, understated life. Scenes, such as Daniel’s first job at a mechanic’s garage or his burgeoning romantic feelings for a young girl, are depicted with an almost poetic languor, capturing the minutiae of youth with unparalleled authenticity.

Critics, however, were divided. Some hailed the film as a masterclass in subtlety, while others dismissed it as a meandering narrative lacking the potent confrontations of Eustache’s other works. However, they missed the film’s strength in its restraint. Instead of explosive monologues or sweeping dramatic arcs, My Little Loves is grounded in the quiet moments that, when pieced together, form the mosaic of adolescence.

Positioned against Eustache’s oeuvre, this film stands out for its sheer gentleness. Unlike the caustic relationships in The Mother and the Whore, My Little Loves revels in innocence. One cannot forget the scene where Daniel experiences the cinema for the first time; his wonderment, beautifully framed in Eustache’s signature realism, resonates with any viewer who has felt the magic of film.

Jean Eustache: Themes and Style

Themes:

- Intimacy and Relationships: Eustache was deeply fascinated with the nuances of human relationships, often exploring the intricacies of love, infidelity, and the emotional aftermath. His characters navigate complex emotional terrains, as seen in The Mother and the Whore.

- Transition and Modernity: Many of his films grapple with transitioning from tradition to modernity, particularly post-war France’s changing values and societal norms.

- Adolescence and Coming-of-Age: Films like My Little Loves delve into the formative years, capturing the trials, tribulations, and wonders of growing up.

- Autobiographical Elements: Eustache often infused his films with personal experiences, rendering an authentic touch to the narratives.

Styles:

- Realism: One of the hallmarks of Eustache’s style is his commitment to authenticity. His films often blur the line between documentary and fiction, using naturalistic dialogue and settings.

- Long Takes: Eustache favoured extended shots, allowing scenes to breathe and evolve organically, enhancing realism.

- Dialogues and Monologues: His films, especially The Mother and the Whore, are marked by extended monologues where characters engage in deep introspection.

- Dual Narratives: Eustache occasionally presented two versions of the same story within a single film, challenging perceptions of reality and fiction, as seen in Une sale histoire.

Directorial Signature:

- Blurring Genres: Eustache had an uncanny ability to merge documentary-style filmmaking with fictional narratives. This unique melding made his films both an observation and a statement.

- Revisiting Narratives: A distinct aspect of his directorial approach was revisiting themes, stories, or events, capturing them from different angles or at other times, as evidenced in La Rosière de Pessac.

- Subtlety over Spectacle: Unlike some of his contemporaries who preferred flamboyance, Eustache’s works lean towards subtlety. His stories unravel gradually, often in mundane settings, capturing profound human experiences without resorting to melodrama.

- Voyeuristic Lens: His camera often serves as a silent observer, documenting the raw emotions and events without overtly influencing them, creating a voyeuristic experience for the audience.

Further Reading:

Books:

- An Essay on Jean Eustache’s La Maman et la Putain by Matt Longabucco

Articles and Essays:

- The Mother and the Whore Revisited by Richard Brody, The New Yorker

- ‘The Dirty Stories of Jean Eustache’: A Rarely Seen French Director by Kristin M. Jones, The Wall Street Journal

- Bad Company: Jean Eustache’s Erotics of Estrangement by Beatrice Loayza, Art Forum

- Desire & Despair: The Cinema of Jean Eustache by Jared Rapfogel, Senses of Cinema

- Jean Eustache: He Stands Alone by Martine Pierquin, Sight & Sound

- Absolute Necessity by Liza Katzman, Film Comment

- The Film That Shattered the Mystique of French Cinema by Joan Dupont, The New York Times

Jean Eustache – The 178th Greatest Director