Elia Kazan was an influential American director noted for his compelling dramas that often tackled significant social issues. His actor-focused approach, deeply rooted in his background as an actor and co-founder of the Actors Studio, was integral in shaping the performances in his films. He was an expert in exploring his characters’ psychological depth and capturing their emotional life, often against a backdrop of societal tension. Best known for his films like Gentleman’s Agreement, A Streetcar Named Desire, On the Waterfront, and East of Eden, Kazan’s distinctive style combined realism and innovative cinematic techniques to deliver remarkable depth and authenticity.

Born to Greek parents in Istanbul, Kazan moved to the United States as a child. After his early acting career, he transitioned to directing, successfully making a mark in theatre and film. His close collaborations with renowned playwrights such as Tennessee Williams and Arthur Miller enabled him to translate their works into some of the most memorable American films of the era. However, his career was not without controversy, particularly during the Hollywood Blacklist period when his decision to name names proved highly contentious.

Many of Kazan’s films dealt with important social issues, providing a platform for audiences to reflect on societal concerns. He was unafraid to tackle challenging themes, taking on anti-Semitism in Gentleman’s Agreement, racism in Pinky, and corruption in labour unions in On the Waterfront. His characters’ personal and psychological depth played a significant role in his approach to these issues, enabling him to craft intimately personal narratives.

Method Acting and Status Quos

Kazan’s filmmaking style was marked by a strong emphasis on realism. He captured authentic settings often by shooting on location, and his dialogue and situations were grounded in reality. This dedication to realism extended to his character development, where he drew on his acting background and Method Acting technique to elicit powerful performances from his actors, often resulting in their delivering career-best performances.

In terms of cinematic style, Kazan’s work is known for its dynamism and innovation. From his pioneering use of widescreen CinemaScope in East of Eden to the gritty, location-based shooting of On the Waterfront, he continually sought to push the boundaries of the medium. His technical innovation, actor-centric approach, and dedication to addressing social issues contributed to his unique and enduring directorial style.

Kazan’s influence on filmmaking has been significant, shaping the approaches of directors and actors worldwide. His emphasis on personal conflict and social issues helped to pave the way for more complex narratives in Hollywood cinema. Filmmakers like Martin Scorsese and Francis Ford Coppola have cited his influence, acknowledging the impact of his work on their own. Despite the controversies surrounding his career, Kazan’s lasting impact on cinema history is unquestionable. His work was widely recognised and received numerous awards, including multiple Academy Awards, cementing his legacy as one of the most important figures in American film.

Elia Kazan (1909 – 2003)

Calculated Films:

- A Tree Grows In Brooklyn (1945)

- A Gentleman’s Agreement (1947)

- A Streetcar Named Desire (1951)

- On The Waterfront (1954)

- East of Eden (1955)

- A Face in the Crowd (1957)

- Splendour in the Grass (1961)

- America, America (1963)

Similar Filmmakers

Elia Kazan’s Top 10 Films Ranked

1. On The Waterfront (1954)

Genre: Drama, Crime, Melodrama

2. A Face in the Crowd (1957)

Genre: Drama, Satire

3. East of Eden (1955)

Genre: Melodrama, Drama

4. A Streetcar Named Desire (1951)

Genre: Melodrama, Drama, Southern Gothic

5. A Tree Grows In Brooklyn (1945)

Genre: Drama, Coming-of-Age

6. Splendor in the Grass (1961)

Genre: Coming-of-Age, Melodrama, Romance

7. Wild River (1960)

Genre: Drama

8. America, America (1963)

Genre: Drama, Period Drama

9. Baby Doll (1956)

Genre: Drama, Melodrama, Black Comedy

10. Panic in the Street (1950)

Genre: Thriller, Film Noir

Elia Kazan: Controversy On and Off Screen

Elia Kazan, born Elias Kazanjoglou on September 7, 1909, in Constantinople (now Istanbul), Turkey, grew up against a backdrop of cultural hybridity. Immigrating to the U.S. with his Greek parents in 1913, Kazan’s early life was emblematic of the American Dream—a dream defined by the struggle of the immigrant experience. The Kazan family arrived in New York’s upper-class neighbourhoods but moved to Harlem due to financial difficulties, starkly contrasting their previously affluent life.

This early exposure to the oscillations of fortune and the narratives of the dispossessed would inform Kazan’s unique approach to the world of drama. As he entered into his 20s, Kazan pursued acting, joining the Group Theatre in 1932. The Group Theatre, known for its strong emphasis on realism, echoed the leftist political sentiment of the time. It championed a kind of theatre that mirrored real-life experiences, deeply resonating with Kazan’s immigrant background.

However, his transition from acting to directing in the late 1930s truly marked the beginning of Kazan’s career. The post-war era was ripe for a new kind of dramatic storytelling that delved into the psyche of its characters and reflected the social and political realities of the time.

As a director, Kazan was a perfectionist, not in technical precision but in extracting raw, emotional authenticity from his actors. His ability to guide actors to such depths can be partly attributed to his association with The Actors Studio.

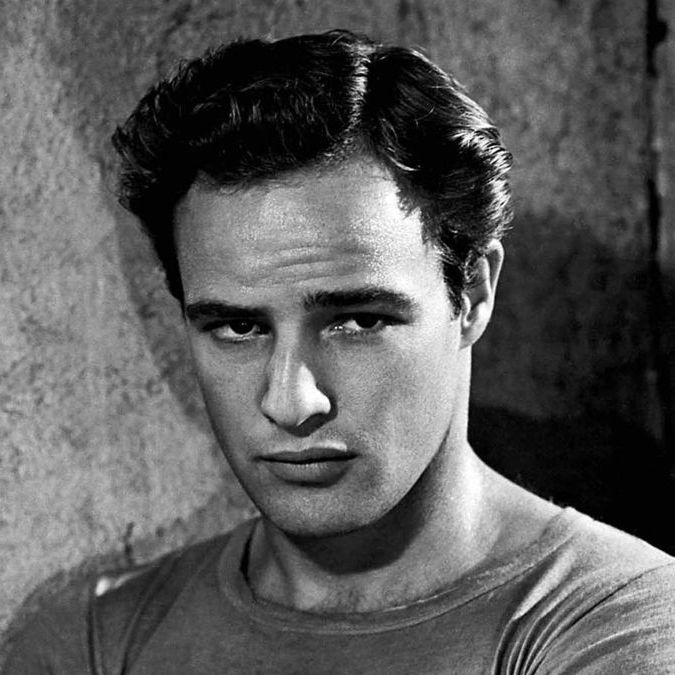

Kazan, alongside Cheryl Crawford and Robert Lewis, founded The Actors Studio in 1947. This institution would become legendary in American theatre and film, heralding the birth of Method Acting. Pioneered by Lee Strasberg, the Method encouraged actors to draw upon their personal experiences and emotions to deliver more genuine performances. In time, stars like Marlon Brando, James Dean, and Marilyn Monroe would emerge from the studio.

In 1945, just two years before the establishment of The Actors Studio, Kazan transitioned into filmmaking, debuting with the poignant A Tree Grows in Brooklyn. The film, an adaptation of Betty Smith’s coming-of-age novel, presented a semi-autobiographical tale set in the tenements of Brooklyn. It was a microcosm of the American Dream—resilient, tenacious, yet fraught with trials. The narrative, echoing Kazan’s journey from obscurity to recognition, was rendered with such sensitivity that it immediately marked him as a director of formidable depth.

His subsequent film, Gentlemen’s Agreement, showcased Kazan’s predilection for diving into the social and political quagmires of the time. Addressing the taboo of anti-Semitism in post-war America, the film was as audacious in its theme as it was subtle in its storytelling. Starring Gregory Peck, the narrative follows a journalist who poses as a Jew to experience and expose the latent prejudices of society. It won Kazan his first Academy Award for Best Director, solidifying his status as a filmmaker and cinematic commentator on American socio-political realities.

This period of 1947-1949 was a fertile one for Kazan. He dabbled in various genres, ensuring his unique fingerprint was evident. Pinky was another film that ventured into the realm of societal prejudice, this time confronting issues of racism. With these films, he showcased his craftsmanship and conscious decision to engage the troubling questions of American identity.

Kazan ushered in the ’50s with a shift in cinematic palette, choosing the noir-ish milieu of New Orleans in Panic in the Streets. A thriller that interweaved public health issues with gritty crime, it showcased Kazan’s ability to blend genre cinema with underlying social commentary. A deadly infectious disease, a city under the spectre of an epidemic, and the race against time to contain it – all these elements were interlaced masterfully, with Kazan painting a vivid canvas of fear, resilience, and determination.

Yet, his subsequent work, A Streetcar Named Desire, would truly define Kazan’s career. Teaming up with playwright Tennessee Williams and bringing the visceral power of the stage to the silver screen, Kazan delivered a cinematic tour de force. The sizzling streets of New Orleans provided the backdrop for this tale of desire, delusion, and decay. Marlon Brando’s Stanley Kowalski, with his brutish charm, became emblematic of Kazan’s genius in character portrayal. With Kazan’s intuitive touch, the story wasn’t just a family drama but a haunting, raw examination of human frailty and the ravages of time.

A year later, in 1952, Kazan shifted gears and historical periods with Viva Zapata! This biographical film on the revolutionary Emiliano Zapata, starring Marlon Brando, underscored Kazan’s range. Here was a director who could shift from the alleys of New Orleans to the Mexican Revolution, always ensuring that the human element, the throbbing heart of his narratives, remained constant.

However, the early ’50s was not just a period of cinematic exploration for Kazan but also a time of personal turmoil. In 1952, he testified before the House Committee on Un-American Activities (HCUA), naming eight former colleagues as members of the Communist Party. This testimony proved to be one of the most divisive moments in Hollywood history. While many in the industry believed Kazan was safeguarding his career, others saw it as a betrayal of friends and principles. This incident would cast a shadow on Kazan’s personal and professional life, and its ramifications would ripple through his subsequent films.

The first post-testimony film, On The Waterfront, seemed to be an artistic reflection on Kazan’s own struggles with the HCUA fallout. Marlon Brando’s portrayal of Terry Malloy, a longshoreman who stands against union corruption, was interpreted by many as Kazan’s justification for his testimony. The infamous line, “I coulda been a contender,” echoes the disillusionment and sacrifice that defined his journey.

In 1955, Kazan embarked on a cinematic exploration of John Steinbeck’s East of Eden. The tale of familial discord set against the sprawling Salinas Valley in California was another feather in his cap. It introduced James Dean to the world, an actor who embodied the Method’s raw emotional energy. The film’s depiction of generational conflicts, sibling rivalries, and the eternal quest for parental approval showcased Kazan’s ability.

The latter half of the 1950s witnessed him continue his hot run of form. Baby Doll, a sexually charged narrative penned by Tennessee Williams, presented a scathing take on societal mores and moral decay in the American South. With its provocative theme and candid portrayal, Baby Doll ruffled many feathers, but its controversies proved his continued audacity.

In 1957, A Face in the Crowd emerged as one of Kazan’s most prescient works. Charting the meteoric rise of a folksy, rough-around-the-edges singer to national prominence and his eventual descent into megalomania, the film foreshadowed the age of celebrity culture and media manipulation. In an era before the ubiquity of social media and the 24-hour news cycle, Kazan’s incisive lens turned to the dangerous liaisons between media, power, and public influence, proving his capacity for keen foresight.

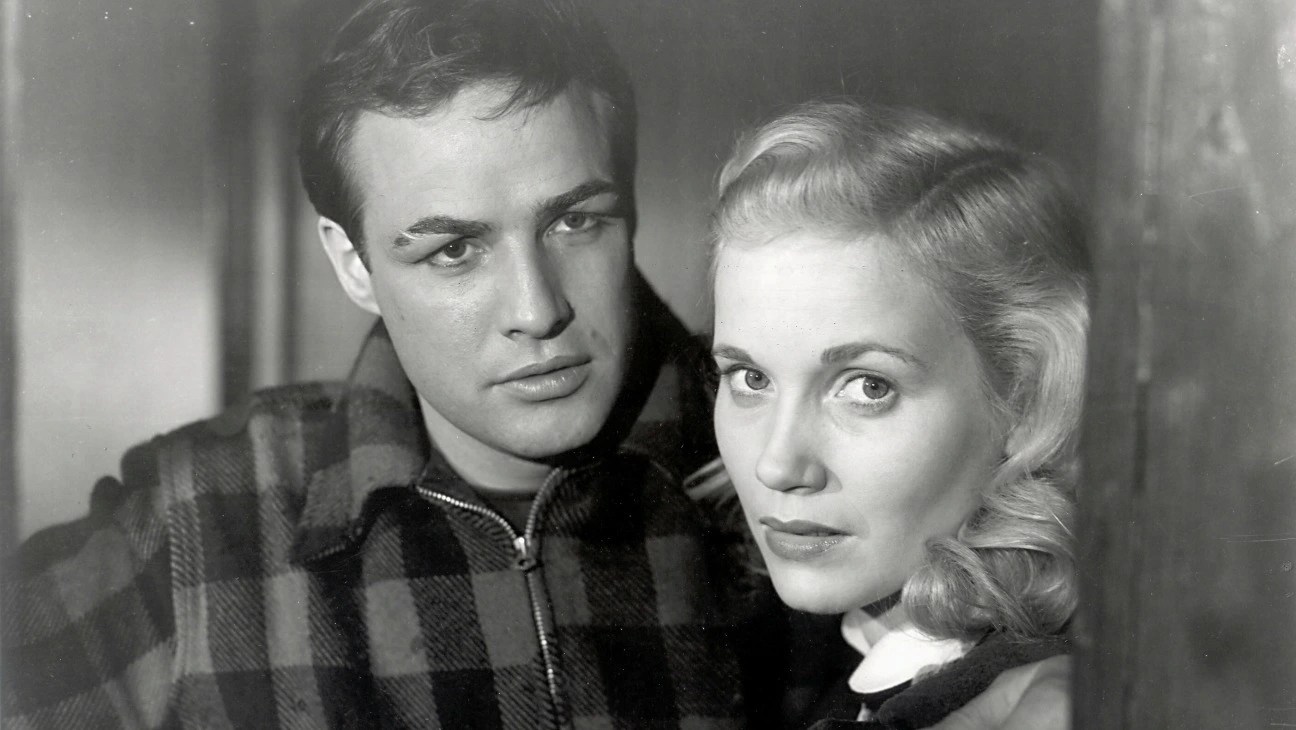

1961’s Splendor in the Grass, penned by playwright William Inge, was a tender yet heart-wrenching examination of young love, societal expectations, and the mental toll of suppressed desires. Starring Natalie Wood and Warren Beatty early in their careers, the film’s lyrical quality juxtaposed with its visceral emotional intensity showcased the director’s unique talent in melding aesthetics with raw sentiment.

Two years later, in 1963, Kazan turned to a deeply personal narrative with America America. Drawing upon his family’s emigrant experience, the film served as both a homage to his Greek roots and a tribute to the myriad immigrant stories that make up the American tapestry. It was a poignant, introspective look into the sacrifices, hopes, and dreams of those seeking a better life on foreign shores.

The subsequent years saw Kazan’s fervour wane. Films such as The Arrangement and The Visitors lacked the indelible impact of his earlier works. They weren’t bad, but they lacked the edge or beauty of his prior films. By the time of his last directorial effort, The Last Tycoon, adapted from F. Scott Fitzgerald’s unfinished novel, it became evident that while the flame of Kazan’s talent still flickered, it had mellowed with time.

Elia Kazan passed away on September 28, 2003, but left behind a cinematic and theatrical legacy that few could rival. Throughout his career, he introduced audiences to new talents, pioneered innovative acting techniques, and tackled themes many would have shied away from.

Yet, his legacy remains somewhat shadowed by his HCUA testimony. For many, this act was seen as a betrayal, a compromise of integrity in the face of personal ambition. The rifts this caused in Hollywood were deep, leading to decades-long estrangements and casting a pall over what was otherwise a stellar career.

Most Underrated Film

Released in 1957, A Face in the Crowd appears to be years ahead of its time, grappling with uncannily relevant themes in today’s media-driven age. It delves into the meteoric rise of Larry “Lonesome” Rhodes, played with electric intensity by Andy Griffith, from an Arkansas jail cell to national stardom. Shot primarily on location in Arkansas, the film achieves a tangible atmosphere that adds authenticity to its portrayal of rapid fame and its disillusioning aftermath.

A common criticism at the time was that the narrative felt exaggerated, almost implausible. Some critics argued that the public couldn’t be so easily swayed by a singular charismatic figure. But history, especially in our current media landscape context, has proven Kazan’s vision to be eerily prescient. The film exposes the seductive allure of populism and the malleability of public opinion in the hands of a magnetic personality, amplified by the megaphone of mass media.

One scene that stands out is when Rhodes, unaware that his microphone is still on, derides his audience as “idiots” and “morons.” This moment underscores his duplicitous nature and accentuates the dangers of blind adulation.

A Face in the Crowd may not have the overt emotional turmoil of A Streetcar Named Desire or the moral weight of On the Waterfront. Still, its brilliance lies in its prophetic insights. It’s a searing commentary on fame, media manipulation, and the transient nature of public favour.

Elia Kazan: Themes and Style

Themes

- Societal Critique: Many of Kazan’s films functioned as incisive critiques of contemporary society, from the anti-Semitism explored in Gentleman’s Agreement” to the corrupt union politics in On the Waterfront.

- Conflict & Morality: Personal struggles with morality were at the heart of many of Kazan’s narratives. This was often embodied in characters grappling with inner dilemmas, be it Terry Malloy’s struggle in On the Waterfront or the broader moral questions in A Streetcar Named Desire.

- Identity and Self-Discovery: From the immigrant experience in America America to Cal Trask’s self-discovery journey in East of Eden, Kazan frequently explored characters searching for their place in the world.

- Effects of Fame & Media: A Face in the Crowd stands out as a potent examination of the rise to fame and media’s transformative (often corrupting) power.

Styles

- Realism: Inspired heavily by his theatre background and the Method acting approach, Kazan’s films often leaned towards realism, providing an authentic, immersive experience.

- Character Depth: Kazan had an unparalleled skill in developing layered, multidimensional characters, thanks in part to his deep work with actors and his appreciation for the intricacies of the human psyche.

- Collaboration with Playwrights: Having adapted several plays into films, Kazan often collaborated closely with playwrights, ensuring that the original work’s essence was maintained while making it cinematically compelling.

Directorial Signature

- Actor’s Director: Kazan’s theatre background made him an “actor’s director.” He had a unique ability to extract deep, emotionally resonant performances from his actors, making legends out of the likes of Marlon Brando and James Dean.

- Use of Locations: Kazan often chose to shoot on location, adding a layer of authenticity to his films. The gritty streets of New York in On the Waterfront or the genuine Southern ambience in A Streetcar Named Desire are testament to this approach.

- Narrative Build-up: Kazan was known for his slow-burning narratives, culminating in intense climaxes. He allowed the story to simmer, building tension gradually until it reached a boiling point, resulting in some of cinema’s most memorable moments.

- Deep Focus: While many directors might opt for close-ups in emotionally charged moments, Kazan often used deep focus shots, placing characters within their environments and emphasising their relation to the world around them.

- Personal & Political Intertwine: Kazan’s experiences and the socio-political environment frequently influenced his films. Whether it was his immigrant background echoing in America America or his HCUA testimony influencing the narrative of On the Waterfront, the personal and political were often inextricable in his work.

Further Reading:

Books:

- Elia Kazan: A Life by Elia Kazan – Kazan’s own autobiography offers insights into his personal life, professional journey, and the choices he made throughout his career.

- Elia Kazan: A Biography by Richard Schickel – This detailed biography provides an extensive overview of Kazan’s work and its impact on American cinema and theatre.

Articles and Essays:

- Elia Kazan’s America by Estelle Changas, Film Comment

- Looking for Truth: Elia Kazan’s East of Eden and post-Korean War America by Mary Hamer – Senses of Cinema

- Kazan, Elia by Jeremy Carr, Senses of Cinema

Documentaries:

- A Letter to Elia, directed by Martin Scorsese

Elia Kazan: The 77th Greatest Director