Dziga Vertov, born David Abelevich Kaufman, was an influential Soviet director best known for his pioneering work in documentary filmmaking, particularly within the cinéma vérité style. His most renowned film, Man with a Movie Camera, is celebrated for its innovative use of cinematic techniques and its rejection of traditional narrative structures. Vertov’s passionate belief in cinema as a unique art form capable of revealing ‘film truth’ has profoundly impacted the evolution of documentary film.

Before he made his mark in cinema, Vertov worked as a newsreel editor during the Russian Civil War. The establishment of the newsreel series Kino-Pravda marked the start of his quest for cinematic truth, with his innovative techniques bringing a refreshing perspective to filmmaking. Vertov masterfully employed a multitude of experimental techniques such as double exposure, fast and slow motion, freeze frames, jump cuts, split screens, extreme close-ups, and tracking shots to document reality, as seen in his early Kino-Pravda series.

Vertov’s approach to cinema was marked by his adoption of the Soviet Montage Theory. This theory underlined his work, with a firm belief in the power of editing to create meaning and evoke emotion. Man with a Movie Camera showcases a myriad of editing techniques in its portrayal of a city’s daily life. The film exemplifies Vertov’s view of cinema as an independent art form. It strays from traditional storytelling methods rooted in theatre and literature, instead using its unique properties to communicate with the audience.

Vertov’s contributions to film, especially documentary and experimental cinema, are invaluable. His emphasis on innovative techniques and the montage theory to extract and present ‘film truth’ revolutionised how documentaries were made. Furthermore, his film Man with a Movie Camera is considered a significant contribution to the city symphony genre. With a profound legacy influencing directors like Jean-Luc Godard and Chris Marker, Vertov’s work continues to inspire filmmakers globally, asserting his essential place in film history.

Dziga Vertov (1896 – 1954)

Calculated Films

- Anniversary of the Revolution (1918)

- A Sixth Part of the World (1926)

- Man With A Movie Camera (1929)

- Enthusiasm (1930)

Similar Filmmakers

- Aleksander Dovzhenko

- Chris Marker

- D. A. Pennebaker

- Esfir Shub

- Fernand Leger

- Grigori Aleksandrov

- Hollis Frampton

- Ilya Kopalin

- Jean Rouch

- Jean-Luc Godard

- Jean Vigo

- Joris Ivens

- Lev Kuleshov

- Maya Deren

- Sergei Eisenstein

- Stan Brakhage

- Vsevolod Pudovkin

- Walter Ruttmann

8 Dziga Vertov Films You Should Watch

Anniversary of the Revolution (1918)

Genre: Compilation Documentary, Political Documentary, Propaganda Film

Kino-Eye (1924)

Genre: Documentary, Essay Film, Soviet Montage

Kino Pravada No 21 (1925)

Genre: Newsreel, Propaganda Film, Essay Film

A Sixth Part of the World (1926)

Genre: Documentary, Soviet Montage, Propaganda Film

The Eleventh Year (1928)

Genre: Soviet Montage, Documentary, Propaganda Film

Man With A Movie Camera (1929)

Genre: City Symphony, Essay Film, Soviet Montage, Experimental

Enthusiasm (1930)

Genre: Documentary, Propaganda Film, Essay Film, Soviet Montage

Three Songs About Lenin (1934)

Genre: Propaganda Film, Essay Film, Documentary

From Lens to Lenin: Dziga Vertov’s Revolutionary Revelations

Born as David Abelevich Kaufman in 1896 in what is Bialystok, in modern Poland, Vertov’s early life was marked by the same restless energy that would characterise his entire filmmaking career. At the time of his birth, Bialystok was an important hub for Jewish life and thought. In these streets, Vertov was first exposed to the magic of storytelling, though it would be some time before he channelled it through the lens of a camera.

However, it wasn’t just the cultural milieu of Bialystok that shaped him. The broader socio-political upheavals of early 20th-century Europe, most notably the Bolshevik Revolution, would cast a long shadow over Vertov’s life and work. As the world around him churned with revolution and change, young Kaufman was also transforming. Adopting the pseudonym ‘Dziga Vertov’, which translates roughly to “spinning top”, he seemed to signal his restless, ever-turning nature to the world.

Post-revolutionary Russia was a place of paradoxes – an old empire giving way to new ideals, with all the upheaval and potential such transitions bring. For Vertov, this period represented an opportunity. Moving to Moscow in his early twenties, Vertov soon found himself amidst a group of young revolutionaries, not of politics, but of film.

This new world also led him to two of his most significant collaborators: his wife, Elizaveta Svilova, and his brother, Mikhail Kaufman. Svilova wasn’t just his partner in life but a brilliant editor whose keen sense for rhythm and juxtaposition proved invaluable in bringing Vertov’s visions to life. Together, they would redefine what cinema could achieve, pushing its boundaries both in form and content.

Mikhail Kaufman, Vertov’s younger brother, brought his own brand of genius to the table. As a cameraman, he was Vertov’s eyes in the field, capturing raw footage that would later be sculpted into masterpieces in the editing room. The trio would come to redefine cinema.

Film Truth

One of their pioneering endeavours was Kino-Pravda (Film Truth). Starting in 1922, this series of newsreels wasn’t just a mere documentation of events but an effort to uncover deeper truths. With Vertov’s guiding philosophy and Kaufman’s diligent camerawork, Kino-Pravda offered a window to Soviet society.

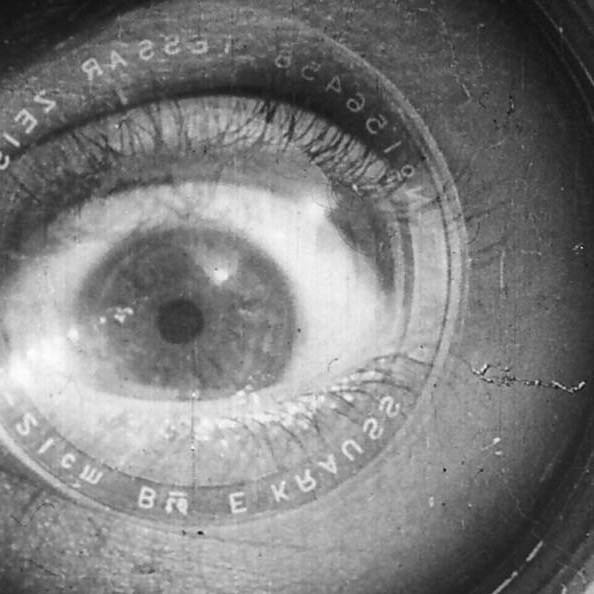

Yet, even as he was breaking new ground with Kino-Pravda, Vertov was conceiving a more radical notion: the idea of the ‘Cine-Eye’. For Vertov, the camera was more than just a tool; it was an extension of human perception, superior in many ways to the human eye. He dreamt of a cinema that didn’t merely represent reality but enhanced and illuminated it.

The Cine-Eye theory encapsulated Vertov’s belief in the camera’s ability to access truths beyond human perception. He envisioned a cinematic style that was free from the constraints of traditional narratives or theatrical influences. For Vertov, cinema’s strength lay in its ability to capture fragments of reality, which, when stitched together, presented a deeper, more profound understanding of the world. No film exemplifies Vertov’s Cine-Eye theory like his greatest film, Man with a Movie Camera.

The Man with a Movie Camera

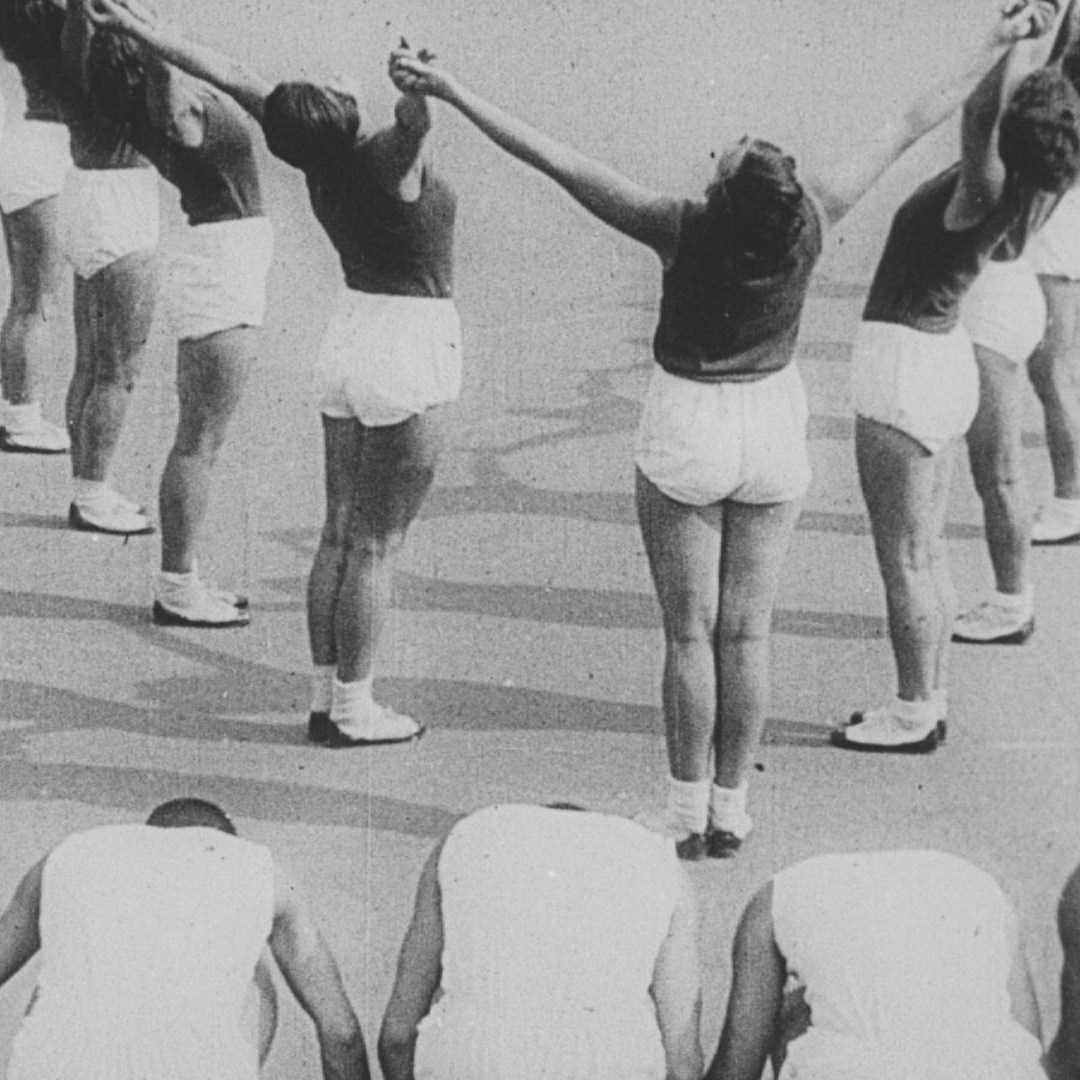

The film was an exhilarating symphony of life in a Soviet city. Yet, it defied every convention of filmmaking of its time. Bereft of actors, dialogues, or a linear narrative, the film was a montage of everyday moments, a collage of urban Soviet life. Vertov, with his brother Kaufman’s invaluable contributions as the primary cinematographer, sought to create an experience that was both universal and deeply personal, all seen through the unwavering gaze of the Cine-Eye.

In this masterstroke, Vertov did not just present a day in the life of a city; he showcased the very pulse, rhythm, and heartbeat of urban existence. The montage technique, meticulously edited by his wife Svilova, created juxtapositions at once jarring and poetic, sparking a dialogue between contrasting images. The film was a declaration, a testament to the power of cinema to reflect and amplify reality.

While Man with a Movie Camera remains Vertov’s most celebrated work, his later career still featured some gems. However, the winds of change in the Soviet Union, particularly under Stalin’s regime, were not always favourable to Vertov’s avant-garde inclinations. The rise of Socialist Realism as a state-approved art form meant that Vertov’s groundbreaking, non-linear style often found itself at odds with the prevailing orthodoxy. Despite the challenges, he continued to work, never compromising his vision, producing films like Three Songs About Lenin and Lullaby.

Post-1930s & Legacy

Unfortunately, Vertov’s career essentially ended here shortly before WW2. He’d live another two decades and make three films post-30s, but he held little creative control over any of them. He passed in 1954, believing himself forgotten by time. But his shadow was felt in the West.

The 1960s saw the emergence of the Dziga Vertov Group, an avant-garde film collective founded by filmmakers Jean-Luc Godard and Jean-Pierre Gorin in France. Taking its name from the master, the group was deeply influenced by Vertov’s radical approach to filmmaking, marrying political ideology with cinematic experimentation.

Moreover, the essence of Vertov’s Cine-Eye philosophy could be seen breathing life into the Cinema verite movement. This style of documentary filmmaking, grounded in authenticity and capturing genuine moments, owes a significant debt to Vertov’s early explorations with Kino-Pravda. The Situationists, with their disdain for the passive consumption of art and their emphasis on creating situations to jolt people out of their complacency, found a spiritual ancestor in Vertov.

Across the Atlantic, the Direct Cinema movement in North America, emphasising observing and capturing life as it unfolded, without interference or overt narrative structures, was a clear echo of Vertov’s ethos. In Britain, the Free Cinema movement, grounded in a desire for authenticity and an emphasis on the everyday, bore Vertov’s unmistakable imprint.

Unknowingly and against the odds, Vertov has never been forgotten. His Man with a Movie Camera continues to be routinely considered one of the greatest films ever made almost a century since its creation.

Most Underrated Film

Vertov’s first full-length sound film, Enthusiasm, remains underappreciated; it might not be as good as Man with a Movie Camera, but it’s still an overlooked gem. Venturing into the coal mines of Donbas and the steel factories of Kryvyi Rih, Vertov sought to capture the essence of industrial Soviet life. With the novel incorporation of sound, he immerses the viewer in a cacophony of industry, juxtaposing the rhythmic machinations of machinery with the fervour of human endeavour. The film was a symphony, not of instruments, but of raw, pulsating life.

Yet, at best, the reception to Enthusiasm was mixed. Critics accused it of being overly cacophonous, with its innovative sound design perceived as noisy rather than artistry. In retrospect, these are tired complaints; the film is an ode to the workers, capturing their sweat, rhythms, and aspirations. And while it’s undeniably celebratory, it’s also reflective, offering a meditation on modernity and progress.

Dziga Vertov: Themes and Style

Themes:

- Reality as Construct: Vertov believed cinema had the power to capture reality in its most authentic form, untouched by the artifice of staged cinema. His works often revolved around the raw and unscripted moments of daily life.

- Industrialisation and Progress: A recurring theme, especially in Enthusiasm, is the relationship between man and machine in the industrial age.

- Political Ideology: As an artist in the Soviet Union, Vertov’s works often carried undertones (sometimes overtones) of political ideology, celebrating the achievements of socialism and the proletariat.

- The Power of Observation: Many of Vertov’s works are observational, emphasising the importance of the camera as a neutral observer, capturing life as it unfolds.

Styles:

- Montage Technique: Inspired by the likes of Eisenstein, Vertov took the montage to new heights. His rapid cuts, juxtapositions, and non-linear narratives create poetic contrasts and commentaries, best seen in Man with a Movie Camera.

- Cine-Eye: Vertov’s philosophy that the camera lens could see and capture the world more truthfully than the human eye. His works often used unique angles, movements, and perspectives only a camera could achieve.

- Documentary Realism: Vertov shied away from staged scenes or professional actors. Instead, he favoured the documentary style, showcasing real people in their environments.

- Innovative Sound Design: In Enthusiasm, Vertov explored sound possibilities, juxtaposing natural and industrial noises to craft a unique auditory experience.

Directorial Signature:

- Dynamic Camera Movement: Vertov wasn’t content with static shots. His camera was always in motion – tracking, panning, zooming – capturing life in all its dynamism.

- Self-referential Cinema: Vertov often acknowledged the filmmaking process within his films. For instance, in Man with a Movie Camera, the audience sees the camera, the editing process, and even Vertov’s wife at the editing table.

- Experimentalism: Whether it was his early Kino-Pravda newsreels or later works, Vertov constantly pushed boundaries, trying new techniques and approaches.

- Engaging the Audience: Vertov’s films were not passive viewing experiences. Through his innovative techniques, he sought to engage, provoke, and stimulate his audience, making them active participants in the cinematic experience.

Further Reading:

Books:

- Kino-Eye: The Writings of Dziga Vertov, edited by Annette Michelson – This is a collection of writings by Vertov, including articles, letters, and scripts. These provide a deep insight into his theories and methodologies.

- Lines of Resistance: Dziga Vertov and the Twenties by Yuri Tsivian – A book that delves into Vertov’s influential role in 1920s Soviet cinema and avant-garde movements.

Articles and Essays:

- The Man with the Movie Camera: From Magician to Epistemologist by Annette Michelson, Art Journal

- Dziga Vertov as Theorist by Vlada Petric, Cinema Journal

- Dziga Vertov: The Idiot by Carloss James Chamberlin, Senses of Cinema

Machine Age Poet, Born in Revolution, Stifled Under Stalin by Dennis Lim, The New York Times

Dziga Vertov: The 180th Greatest Director