Chris Marker, a French filmmaker, is widely recognised for his unique and innovative approach to the art of cinema. Known as a pioneer of the essay film, Marker ingeniously blended documentary elements with personal reflections, enabling him to delve into complex philosophical, political, and cultural themes. Renowned for his adept use of montage and voiceover narration, his films often oscillate between documentary, fiction, and avant-garde styles, transcending conventional categorisation. His extensive exploration of time, memory, and history is another defining attribute of his work, most famously exemplified in his cult classic, La Jetée.

Marker began his career as a writer and journalist, a background that heavily influenced his film endeavours. After a few early film projects, he found his essayistic style with Letter from Siberia. Marker’s fascination with political themes and international cultures grew with his travels, profoundly shaping his subsequent works. The experiences and observations gathered during these journeys became integral to his cinematic universe, offering rich socio-political contexts to his narratives.

Marker’s innovative use of montage sets his work apart in cinema. His ability to juxtapose disparate elements like footage, photographs, voiceover, music, and text to evoke rhythm and resonance is prominently demonstrated in his celebrated film, Sans Soleil. This complex interweaving of varied elements helps Marker articulate sophisticated arguments and musings on his chosen subjects, effectively turning his films into visual essays.

Another hallmark of Marker’s films is his engaging use of voiceover. Rather than merely imparting information, his voiceovers often delve into contemplation, commentary, and poetic musings, thereby infusing a personal and philosophical dimension into his films. Coupled with his emphasis on the interplay of time and memory, this technique is especially instrumental in shaping the narrative of La Jetée, a film predominantly narrated through still images.

Marker’s experimental form and innovative use of technology are other distinctive aspects of his work. His early use of still photos in La Jetée and later exploration of digital video and multimedia exhibits his readiness to embrace and incorporate new technologies in his creative process. He ingeniously straddles different forms and styles, which, along with his penchant for political engagement and international focus, contributes to the multi-layered richness of his films.

Chris Marker’s pioneering contributions to cinema have influenced many filmmakers around the globe. Directors such as Jean-Luc Godard, Agnès Varda, and Harun Farocki have expressed admiration for Marker’s groundbreaking style. His innovative approach to montage and his synthesis of documentary, personal reflection, and avant-garde techniques have challenged traditional film norms and expanded the boundaries of cinematic expression.

Chris Marker (1921 – 2012)

Calculated Films:

- Statues Also Die (1953)

- Letter From Siberia(1957)

- La Jetee (1962)

- The Lovely Month Of May (1963)

- A Grin Without A Cat (1977)

- Sans Soleil (1983)

- The Last Bolshevik (1993)

Similar Filmmakers

- Agnes Varda

- Alain Resnais

- Alexander Kluge

- Chantal Akerman

- Claude Lanzmann

- Dziga Vertov

- Godfrey Reggio

- Guy Debord

- Harun Farocki

- Jean Rouch

- Jean-Luc Godard

- Joris Ivens

- Marcel Ophuls

- Patrick Keiller

- Peter Greenaway

- Peter Watkins

- Thom Andersen

- Werner Herzog

Chris Marker’s Top 10 Films Ranked

1. La Jetee (1962)

Genre: Foto Film, Post-Apocalyptic, Romance, Dystopian, Time Travel, Sci-Fi

2. Sans Soleil (1983)

Genre: Essay Film

3. A Grin Without A Cat (1977)

Genre: Essay Film, Political Documentary

4. The Lovely Month of May (1963)

Genre: Cinema Verite, Essay Film

5. The Last Bolshevik (1993)

Genre: Movie Documentary, Essay Film, Biography Documentary

6. Long Day in the Life of Andrei Arsenevich (1999)

Genre: Movie Documentary, Essay Film

7. Letter from Siberia (1957)

Genre: Documentary, Essay Film

8. The Koumiko Mystery (1965)

Genre: Documentary, Essay Film

9. Statues Also Die (1953)

Genre: Art Documentary, Essay Film

10. Level Five (1997)

Genre: Essay Film, Virtual Reality, War Documentary

Chris Marker: 20th Century Renaissance Man

There has rarely been a director as enigmatic as Chris Marker. He fits into so many categories: Documentarian, New Wave, Left Banke, Cinema Verite, etc., yet he doesn’t sit easy in any of them. From his first celluloid moments to his last digital captures, he explored the medium in an iconoclastic way, never stopping to smell the roses or buying into his image.

Although much of Marker’s personal life is shrouded in mystery, we know he was born Christian François Bouche-Villeneuve in 1921 in Neuilly-sur-Seine, France. Marker came of age in the intellectual interwar years and the Second World War. During this time, the young Marker absorbed the literature of French intellectuals like Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir and was involved in radical politics.

Marker was a part of the lesser-known Left Bank movement, often overshadowed by the coexisting French New Wave. The movement was named because its members preferred the bohemian Left Bank of Paris; this movement was defined by its intellectual rigour, documentary-like approach, and exploration of the intersection between fiction and reality.

One of the Left Bank members was Alain Resnais, who would help Marker take his first steps into cinema. Resnais shared Marker’s fascination with memory, time, and montage. Together, they worked on several short films, including Night and Fog, which are important milestones in film history.

However, Marker was much too much an iconoclast to happily play second fiddle, so he went out on his own with films like Sunday in Peking, where he blended an observational style with philosophical ruminations, crafting an intimate and expansive narrative which he would go on to perfect. With its meandering shots and poetic voiceover, the film isn’t just about Beijing—it’s a meditation on history, modernity, and the poetics of space.

Letter from Siberia was groundbreaking, blending documentary footage with staged sequences, political commentary, and personal musings. It showcased Marker’s dexterity in manipulating the visual medium, turning the cold landscapes of Siberia into a canvas on which larger questions about communism, progress, and humanity were painted.

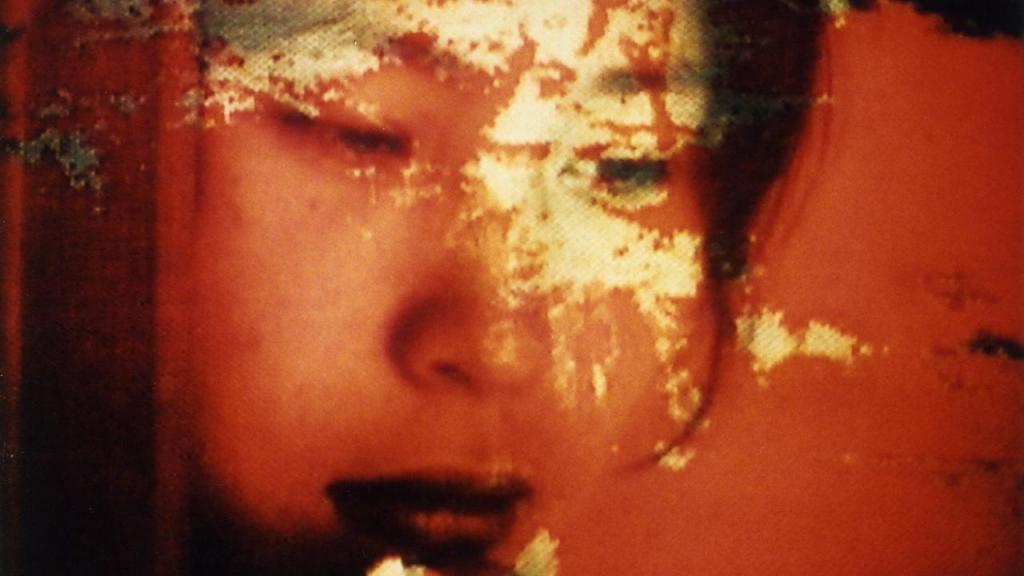

As France became increasingly prominent in world cinema, Marker accidentally became a notable name of the Nouvelle Vague, creating his classic film La Jetée. A 28-minute science fiction short, it is composed almost entirely of still photographs. Yet, its emotional resonance, thematically dense narrative, and hauntingly beautiful imagery elevate the imagery. Centering on the notion of memory and time, Marker postulates a post-apocalyptic world where the key to humanity’s salvation lies in accessing a singular poignant memory. It reflects on the nature of images, memories, and the inexorable march of time. Many, including director Terry Gilliam with his feature 12 Monkeys, have drawn inspiration from this film.

The Parisian spring of 1962, just months after the Algerian War’s denouement, offered a city on the cusp of metamorphosis. And in this transitional phase, Marker brought forth Le Joli Mai. Crafting what can be described as a cinematographic mosaic, Marker roamed the streets of Paris, interviewing a tapestry of its denizens. The film, part documentary and part philosophical inquiry, pierced through the veil of the every day, revealing the hopes, dreams, fears, and regrets of ordinary Parisians. By foregrounding their narratives, Marker showcased the essence of a city that had survived wars and was grappling with the new age’s dreams and disappointments.

During the tumultuous 1960s, Marker, the cinematic voyager, continued pushing boundaries. His work ventured from the furthest reaches of Tokyo in The Koumiko Mystery to the ruminative poetic expressions of The Sixth Side of the Pentagon, which detailed the massive anti-Vietnam War protest march on the Pentagon. Slowly, Marker refined his new form of essayistic documentaries.

Amidst the backdrop of political fervour and social unrest in the late 60s, Marker co-founded SLON (Société pour le Lancement des Oeuvres Nouvelles) – a film collective dedicated to a unique mode of production and distribution. The ethos of SLON was rooted in socialism, emphasising collaborative filmmaking and championing the voices of workers, students, and those marginalised by mainstream media.

May 1968, a month with intense student protests and general strikes in France, further fueled Marker’s commitment to political cinema. His engagement was not merely as a passive observer; he was an active participant, capturing the street’s raw energy and the nascent hopes of a generation daring to imagine a different world. Through SLON, he facilitated the production of direct, unfiltered, and unabashedly political films, placing power and means of cinema in the hands of workers and activists. Post-May 1968, Marker turned more towards SLON and away from more traditional filmmaking.

The early ’70s continued this approach. Delving into diverse subjects, Marker’s films from this era exhibit a polyphonic tapestry of voices and perspectives. The Train Rolls On was one such film, in which Marker interspersed moments of life aboard the Trans-Siberian Railway with the historical and social contexts of the landscapes it traversed.

In 1977, Marker released A Grin Without a Cat, which many consider among his most ambitious works. A sprawling meditation on the global political upheavals of the 1960s and ’70s, the film traverses the continents, from Cuba to Vietnam to Chile, capturing the zeitgeist of revolutionary fervour. With a meticulous collage of archival footage interspersed with Marker’s incisive commentary, it reflected the successes, failures, and enduring legacy of global leftist movements.

Transitioning from the socio-political tumult of the 1970s into the burgeoning technological era of the 1980s and beyond, Marker’s oeuvre reflected a synthesis of the past with a contemplative gaze upon the future. Marker’s fascination with memory persisted throughout the decade, showcased in films like A.K., an intimate behind-the-scenes portrait of Akira Kurosawa.

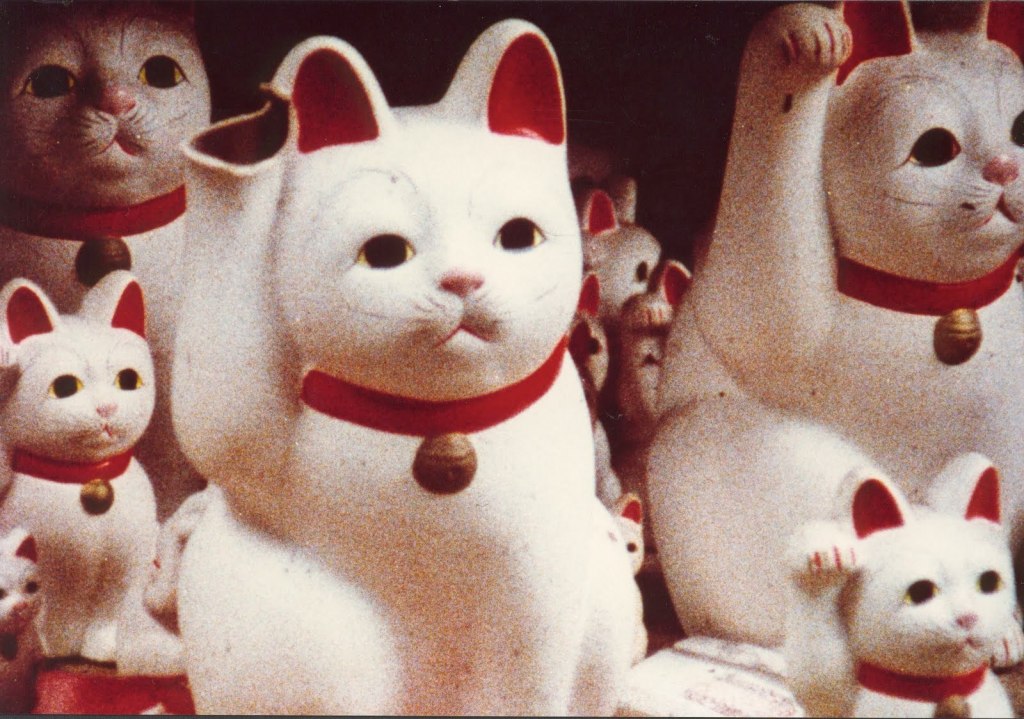

Perhaps no film better exemplifies Marker’s prowess in blending memory, time, and technology than the 1983 masterpiece Sans Soleil. Here, Marker crafts a cinematic letter, a journey spanning from Japan to Guinea-Bissau, all while intertwining musings on memory, culture, and the transient nature of life. Marker’s eloquent narrative, laden with evocative imagery, questions the nature of reality and our attempts to capture it, either through the lens of a camera or the corridors of our memories.

As film turned increasingly digital and directors his age lost their touch, Marker went the other way; he dived into the new era, embracing it with zeal. Level Five stands out, blending narrative cinema with digital artistry. Delving into the Battle of Okinawa’s haunting memories during WWII, the film marries historical footage with futuristic computer interfaces, pondering the nature of memory in the digital age and the ethical dimensions of recreating the past.

Marker’s foray away from traditional film continued into multimedia art installations and CD-ROM projects like Immemory, an interactive exploration of his memories and thoughts. It’s worth noting that of all his old colleagues, Marker was the one who most embraced the modern era.

Yet, despite his keen sense of modernity, Marker remained an enigma. Renowned for guarding his privacy, he rarely gave interviews and shied away from public appearances. This reclusiveness added layers to his mythos, making him akin to a spectral presence whose essence could be felt in every frame of his films but remained elusive in person.

2004’s The Case of the Grinning Cat saw Marker returning to the Parisian streets, chronicling the city’s socio-political landscape post-9/11. In classic Marker style, he finds profound meaning in the seemingly mundane, as graffiti cats become symbols of resistance and introspection in a world grappling with unprecedented changes.

Marker passed away in 2012, still making movies, embracing change, and exploring his classic themes. It feels like, in the years since his death, he has only become more relevant. The essay-film genre he pioneered has found new life in online media. His ruminations on memory, time and technology inspire modern generations, and so many of the greatest directors have cited his importance.

But how do you sum up an artist like Chris Marker? He was an oracle, a beacon, an explorer, and a conquistador. Whose films feel just as new today as they did half a century ago.

Most Underrated Film

From the Cuban revolution to the Vietnam war, Marker takes on the Herculean task of weaving together disparate threads of global revolutionary fervour in A Grin Without A Cat. Chris Marker is one of those directors whose films aren’t really ‘rated’ in the traditional sense. Some of his movies, like La Jetee and Sans Soleil, feature in ‘best of’ polls, but they’re always oddballs there, too. A Grin Without A Cat deserves to sit alongside those two in pride of place. The film is perhaps the greatest political documentary ever, chronicling the rise and fall of leftist movements from the ’60s to the ’70s. True to form, Marker crafts not just a historical document but a tapestry of ideas, ideologies, hopes, and disillusionments.

The movie really encapsulates the dreams and ambitions of a lost generation. Its scope is truly bewildering, and while it does run quite long, it never loses focus. It’s a lyrical, almost poetic work that treats its subjects respectfully. Amidst the cacophony of uprisings and ideological clashes, Marker finds moments of profound humanity, turning the political deeply personal. It becomes a lamentation of lost dreams, reminding us of Yeats’s line: “Too long a sacrifice can make a stone of the heart.”

Chris Marker: Themes and Style

Themes:

- Memory and Time: One of the most recurrent themes, Marker often explored the fragility and resilience of human memory. Films like La Jetée and Sans Soleil delve deep into remembrance, contemplating its role in shaping identities and histories.

- Political Engagement: Marker’s leftist inclinations and interest in revolutionary movements in France and globally are evident in works such as A Grin Without a Cat and his involvement with the SLON collective.

- The Nature of Reality: Pondering the line between reality and perception, Marker’s films often question what we deem ‘real’. This can be seen in his documentaries that blur the lines between fact and interpretation.

- Cinematic Exploration: A self-referential theme, Marker frequently contemplated the nature of filmmaking itself, analysing cinema’s power and limitations in representing truth.

Styles:

- Essayistic Cinema: Marker is often hailed as a pioneer of essay films. He intertwined personal reflection with broader socio-political contexts, crafting films that were both intimate and universal.

- Use of Montage: Borrowing from Soviet cinema and its proponents like Eisenstein, Marker masterfully employed montage to juxtapose imagery, creating new meanings and eliciting strong emotional responses.

- Voice-over Narration: Instead of traditional dialogue-driven narratives, Marker often utilised poetic voice-overs, offering profound insights, musings, and observations.

Directorial Signature:

- Hybrid Documentaries: Straying from conventional documentary techniques, Marker’s works like Le Joli Mai combine elements of fiction, presenting a mosaic of real and imagined narratives.

- Intertextuality: Marker’s films are often laden with references to literature, philosophy, and other films, creating a rich tapestry of intertextual connections.

- Experimentation with Medium: Not just limited to film, Marker ventured into digital technology, multimedia art installations, and even CD-ROM projects, showcasing his adaptability and forward-thinking approach.

- Elusiveness and Anonymity: Marker remained a mystery despite being a prolific filmmaker. His films often revealed personal reflections, but the man remained largely hidden, allowing his work to take centre stage.

- Cats: A quirky signature, but Marker’s love for cats is evident in his personal life and films like The Case of the Grinning Cat, making them emblematic of his idiosyncratic touch.

Further Reading

Books:

- Chris Marker: Memories of the Future by Catherine Lupton – This is one of the most comprehensive books on Marker, providing insight into his vast body of work and the themes he explored.

- Staring Back by Chris Marker – A photo book that collects over fifty years of Marker’s photographs, capturing candid moments of historical figures, street scenes, and personal memories, presented as a visual commentary on the 20th century.

Articles and Essays:

- Chris Marker: Memory’s Apostle by Catherine Lupton, Criterion

- ‘Thrilling and Prophetic’: Why Film-Maker Chris Marker’s Radical Images Influenced So Many Artists by Sukhdev Sandhu, The Guardian

- Chris Marker: Eyesight by Chris Darke, Film Comment

- The Equality of the Gaze: The Animal Stares Back in Chris Marker’s Films by Kierran Argent Horner, Film-Philosophy

- The Owl’s Legacy: In Memory of Chris Marker by Catherine Lupton, Sight and Sound

- The Cats in the Hats Come Back; or “At Least They’ll See the Cats”: Pussycat Poetics and the Work of Chris Marker by Adrian Danks, Senses of Cinema

Chris Marker: The 109th Greatest Director