Got some room for more directors? Because we’ve got some new profiles added.

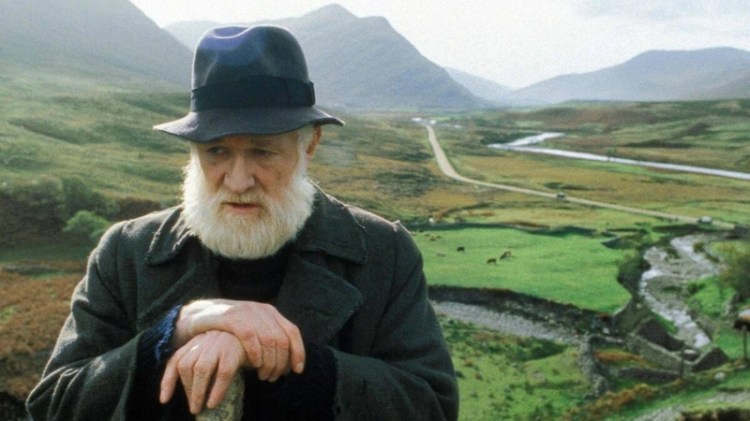

Jim Sheridan

Ireland | 1949 – – | Irish Cinema with a Global Touch

Has there been a better Irish director than Jim Sheridan? It’s hard to think of one. Irish cinema has been a weird place, English-speaking but without a serious mark on film history, perhaps you can say that all the best Irish talents moved to the UK to get work, but even then, the only famous Irish director before the 90s was Terence Young, best known for James Bond films and the box office disaster Inchon.

Since the 90s, Ireland has steadily popped out a fair few talents, Lenny Abrahamson, Tomm Moore, Martin McDonagh, John Crowley, and Terry George, but the two directors who lay the strongest claim to best Irish directors are Neil Jordan and Jim Sheridan, who both appeared on the scene in a similar time.

Perhaps no other director has delved into the Irish identity, both at home and abroad, with such poignant realism as Jim Sheridan. Born in Dublin, Sheridan has forever carried his homeland in his heart, painting it onto the screen with love, sadness, and an unflinching eye.

Think about My Left Foot, In the Name of the Father and The Boxer. These aren’t just movies. They’re pieces of Irish history, soaked in the struggles, hopes and dreams of a people often caught between past and future. My Left Foot is probably his most famous film, which launched Daniel Day-Lewis’ career. Day-Lewis’ performance is the film’s beating heart, but Sheridan’s gentle yet firm direction keeps it on track.

Then there’s In the Name of the Father. A more political piece, sure, but also deeply personal. It’s a story of injustice, of a father and son’s relationship strained and strengthened by wrongful imprisonment. Sheridan never lets politics overshadow humanity; he keeps the focus on the characters, their pain, and their growth. You can feel the damp chill of the prison, the simmering anger, the yearning for justice. It’s real because Sheridan makes it real.

Sheridan, like his characters, is a fighter. He’s fought to tell the stories that matter to him, to his country. He’s embraced both the intimacy of personal tales and the broad strokes of social drama. His filmmaking is unapologetically honest. His Ireland was neither romanticised nor demonised but portrayed with complexity and grace.

Sure, he’s had his missteps (who hasn’t?), but even in his lesser works, there’s always something to appreciate. Sheridan’s career seems to have waned since In America, but in spite of that, he remains a crucial figure in Irish film history. It’s not a coincidence that all of Ireland’s talents started to pop up after Sheridans’ best run of films.

Jordan Peele

United States of America | 1979 – – | Modern Horror Maestro

Has there been a more astronomical rise in modern cinema than Jordan Peele? From sketch comedy to contemporary auteur, he’s dazzled the world’s critics and audiences, all that in the least critically acclaimed genre, horror. What is it about Peele which connects so easily?

Get Out wasn’t just a film. It was a cultural phenomenon where Peele dissected the subtleties of racial tensions, laughed at them and turned the social horror of everyday racism on its head into literal horror on the big screen. He’s continued to dazzle us since with two back-to-back hits, Us and Nope.

His films are littered with easter eggs, intricate details and thrilling sequences. It’s hard to argue he is anything less than the greatest horror director working right now. Yet there is that uneasy feeling that he might be shining too brightly and be overhyped. Does a film from the past ten years deserve to be in the Sight and Sound top 100 as Get Out is? I’m not too sure, but it feels unfair to criticise a director’s talents based on generous critics.

Peele is a beam of refreshing uniqueness in an era of stagnant repetition. He understands the pulse of the present and transforms it and our collective fears and anxieties into unforgettable celluloid snapshots. It’s hard to guess where Peele will go from here. Few directors have achieved the quick critical success in horror as he has. Will he continue to thrill us, or will he overstep the mark and fail to live up to his hype? It’s hard to tell at this point, but from every interview I’ve seen of Peele, he seems to be a fairly self-assured reasonable person, so I hope he won’t jump the shark anytime soon.

Andrzej Zulawski

Poland | 1940 – 2016 | Auteur Visionary Madcap?

Where can you start with Andrzej Zulawski? His inclusion in any list of greatest directors is never secure, but his presence always lingers. What can be said about him which hasn’t been shrieked in some feverish nightmare? Poland in the 1960s was a real hotspot of cinema, with players like Wajda, Polanski and Skolimowski beginning to hammer out some great films. Yet, one of their contemporaries wasn’t quite the same. You see, Andrzej Zulanski’s films have this frenzied air to them, a dark emotional extreme.

Take his 1981 masterpiece, Possession. A brutal dissection of a failing marriage that transforms into something far more sinister and surreal, the film defies easy categorisation. Is it a horror film? A psychological thriller? A work of art that transcends genre, it is emblematic of Żuławski’s entire career.

Born in Poland and often working in France, Żuławski never fit neatly into the prevailing film movements of his time. His works often suffered at the hands of censors, were misunderstood by critics, and were perplexing to audiences expecting conventional narratives. His films are a chaos of emotions, unravelled in frenetic camera movements, punctuated by screams and confrontations that leave the viewer both exhausted and exhilarated.

His early work, like The Third Part of the Night and The Devil, carried the weight of his native Poland’s tumultuous history, while his later French films explored more personal and intimate terrains. On the Silver Globe, a sci-fi epic that the Polish government shut down, remains an incredible example of what Żuławski could achieve despite facing immense obstacles.

And then, there are films like My Nights Are More Beautiful Than Your Days and Fidelity that delve into the torturous dynamics of love and creativity. Żuławski’s camera doesn’t just observe; it invades, dissects, and lays bare the human soul.

But where does he fit regarding great directors? To some, he’s an eccentric footnote, too wild and unruly to ever create a cohesive work comparable to the Titans of cinema. But to others, he is a visionary who dared go where no one else would.

Zulwaski’s films aren’t for the faint of heart. They’re a cinematic assault, thrilling and terrifying to many but rewarding to those who embrace his madness. Zulawski might never have achieved the success his talent deserved, but he remains an icon, a mad poet of cinema, who deserves to be remembered.

Lynne Ramsay

United Kingdom | 1969 – – | Methodical Scot

Born and raised in Glasgow, Lynne Ramsay has slowly established herself as one of the most formidable contemporary directors. She’s not a quick director, having directed just four features over a 20+ year career, but the films she has made have been something special.

Her debut, Ratcatcher, signalled that a powerful new voice had emerged in cinema. It’s a film that’s both delicate and brutal, filled with imagery that haunts and resonates. Ramsay’s gift for visual metaphor and emotional texture is unparalleled, and it’s all there in her first feature.

But We Need to Talk About Kevin really put Ramsay on the international map. A harrowing, devastating film that takes on motherhood and societal violence with a fearless eye. Tilda Swinton’s performance is incredible, but Ramsay’s direction makes it a masterpiece. The way she cuts, moves the camera, and uses colour – it’s a masterclass in visual filmmaking.

Then came You Were Never Really Here, a film that further solidified Ramsay as a director with a unique, uncompromising vision. It’s a brutal, tender film, a piece of art that pushes the boundaries of narrative and challenges the viewer to engage on a deeply personal level.

And yet, despite her immense talent, Ramsay seems to stand at the periphery of the industry’s spotlight. Her projects are often small and intimate, but they pack a punch like a few others. Perhaps it’s because she refuses to conform, to play the Hollywood game, that her name isn’t as widely recognised as some of her contemporaries.

Is she underrated? In some circles, perhaps. But those who know and have experienced the raw power of her films recognise that Lynne Ramsay is one of the most important filmmakers working today.

Joe Dante

United States of America | 1946 – – | Genre Blending Culty Goodness

Loving movies can be a self-serious hobby. It’s hard not to get dragged down by Bergman masterpieces or sometimes look down on casual fare. But it’s important to remember that we fell in love with movies for a reason, entertainment. With a career woven from the threads of horror, comedy, and satire, Joe Dante is a director who’s not afraid to play with convention, gleefully poking at the genres he works in. Films like Gremlins and The ‘Burbs are pure Dante, brimming with his signature blend of horror and humour.

Growing up in the age of classic monster movies and comic books, Dante’s work often feels like an ode to those beloved childhood artefacts. However, they’re far from child’s play. Whether it’s the monstrous chaos of Gremlins or the satirical bite of The Howling, Dante crafts films that entertain and unnerve in equal measure. They are carnival rides that jolt, surprise, and provoke thought.

Consider the gleeful mayhem of Gremlins 2: The New Batch, where Dante’s wild imagination runs amok. Here, the creatures are looser and crazier, reflecting the unchecked capitalism and consumerism of the ’80s. The film is barmy but also a sharply barbed critique. That’s Dante in his element: wild, witty, and wise.

Yet, for all his talent and originality, Dante often feels like the unsung hero of American cinema. He plays in the genre sandbox, where some might mistakenly see only frivolity. But his films, while entertaining, are never shallow.

In Matinee, Dante showcases his deep love for cinema itself, setting the film against the backdrop of the Cuban Missile Crisis and crafting a delightful homage to William Castle-style showmanship. It’s funny, touching, and thoughtful, much like Dante himself.

Unlike some of his contemporaries who either soared to superstardom or flamed out, Dante has navigated a career that’s both steady and adventurous. It’s almost as if he’s too clever for the mainstream, too fun for the art-house crowd. An outlier, certainly, but one whose work continues to charm, challenge, and entertain.