I’ve talked a bit about it before, but the subject is really interesting to me – directors who somehow lost their acclaim as time has gone by; in the previous post, we talked about classic Hollywood directors who have simply been forgotten, denigrated directors and stylised directors who style ended up leaving a bad taste in audiences mouths, but the truth is there are so many more directors who fit the bill.

Unexpected Turns

Let’s start with two relatively modern names, both still directing films and thus both still with hopes of redeeming themselves critically. David Gordon Green has recently directed a trilogy of Halloween films, the first of which got good reviews and the following two receiving fairly poor reviews. Green’s greatest success with the general public was probably Pineapple Express, a stoner comedy starring Seth Rogen and James Franco, which fit into the era of Judd Apatow comedies. However, while the film was Green’s biggest success, it also marked a major turning point in his career.

Gordon Green was in the early 2000s considered one of the best young American directors for his nuanced characteristics and lyrical storytelling in George Washington and All The Real Girls; critics lauded these films for their humanistic approach and emotional depth, and he was seen as a major emerging voice in the industry. That was until Pineapple Express. George Washington remains a well-loved classic, but the critical status of Green hasn’t remained as unaffected. His forays into commercial success have left critics feeling that he has lost his mojo, and his trajectory continues to perplex those critics who once heralded him a future master.

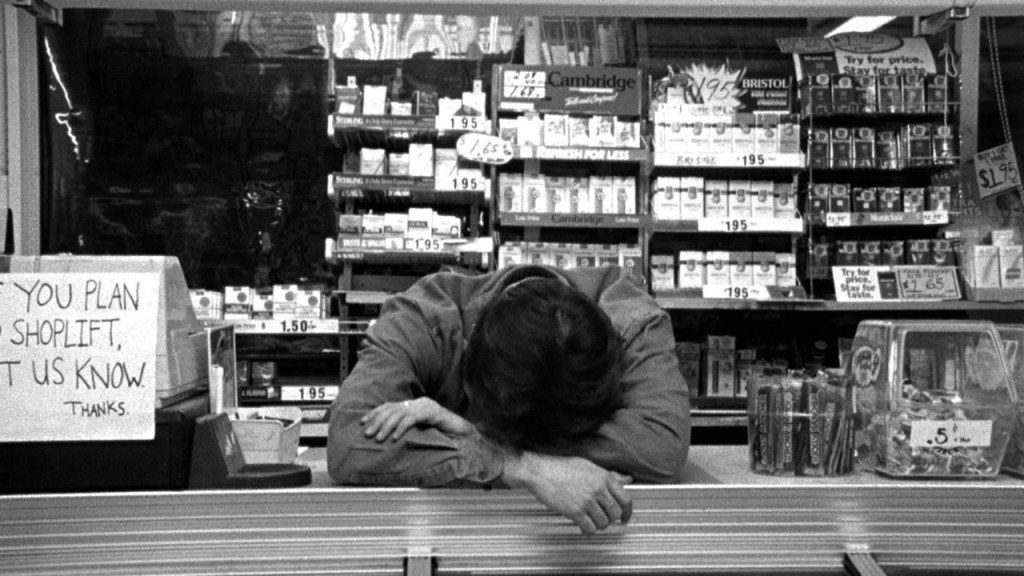

Similarly, Kevin Smith’s unpredictable trajectory has confounded critics and led to some withdrawing their praise. Smith is best known for his pop-culture heavy 1990s films like Clerks and Chasing Amy, which are marked by their relatable characters and sharp dialogue, which made them resonate with Gen-Xers. While Smith’s subsequent films haven’t universally been met with negative acclaim, they have failed to resonate in the same way, lacking that sense of originality which pulsated in his earlier work. Many critics criticise Smith for his catering towards his fanbase and the lack of risks he takes. Indeed, his forays into podcasting and TV have also been said to have negatively affected his reputation. It’s a shame to see Smith’s slow decline in status, Clerks is a great film, yet it feels like every passing year, the detractors’ voices get louder while his supporters get quieter.

Flash in the Pan

Smith and Green’s decline in critical acclaim can be attributed to their focus turning elsewhere. However, both directors still have those core films their fanbases can point to as examples of their talents, even if they aren’t currently using them.

There is another group of directors who were praised as great directors only for critics and audiences to gradually realise that their best movies were more flash-in-the-pan than an example of their vision. John G. Avildsen won the Academy Award for Best Director with Rocky; he directed The Karate Kid and Joe. He has the sort of filmography many directors would dream of, and yet, unlike most Best Director winners, he is essentially a forgotten name. Rocky was Stallone’s auteur vision, and the film gave Avildsen an unfair expectation for the rest of his career; he was never a visionary director, more a competent journeyman who lacked a distinct voice. His critical standing has fallen considerably since the Academy Award ceremony of 1976.

For a brief moment in 2004, Paul Haggis was the most bankable director in the world, he had just directed the Best Picture-winning film Crash, and he had every great movie star knocking at his door. Fast forward 18 years, and you’ll struggle to find a positive comment on Haggis. Crash is routinely considered the worst-ever Best Picture-winning film, and his subsequent films, like In the Valley of Elah and Third Person, failed to make a serious mark commercially or critically. His relative lack of success since Crash, combined with allegations of sexual misconduct, has seen Haggis’ reputation decline substantially.

Blockbuster Disillusionment

The blockbuster medium has always been a fractus place to work as a director. You can make masterpieces like Spielberg or Nolan or could end up making the latest Transformers film. Perhaps the fine line between selling out and achieving commercial success which causes this issue. In recent years we’ve seen a steady stream of indie directors be churned out by Marvel, damaging their reputations for a paycheck; some, like Daniel Destin Cretton, came out of this well, but others haven’t.

J.J. Abrams was a fresh voice in blockbuster cinema in the 2000s, helming Mission: Impossible III and breathing life into Star Trek. He was praised for walking the fine line between commerciality and quality and bringing something new to the blockbuster format. Abrams was seen as the next in line to Spielberg, Hollywood’s next king, yet his work on the Star Wars sequels has damaged his reputation. The Force Awakens was well-received, but The Rise of Skywalker threw his career into freefall. The movie is filled with pandering fan service, lacks a coherent vision and offers nothing original. This led to a reevaluation of all of Abrams’ work, leading critics to conclude that he is too reliant on nostalgia and remixing existing properties rather than offering original ideas.

A less clear-cut example of blockbuster disillusionment could be Ron Howard, the former child star and director of films like Apollo 13, Splash and Cinderella Man has always walked the line between commerce and quality; there have always been detractors of Howard who see him as a mediocre competent filmmaker who has been elevated beyond his talents, but he was awarded the Best Director Oscar for A Beautiful Mind. He has consistently, since the 1980s, been putting out good films.

Howard’s career is an interesting thing; he has roughly the same amount of bad films as good films. His worst works tend to be when he leans too far into sentimentality and conventions and makes box-office schlub like Hillbilly Elegy or The Da Vinci Code. His reputation is also damaged by his safe-pair-of-hands reputation, which saw him given the Solo directing job after a tricky production before he entered. Howard lacks the daring qualities of other Best Director winners. He is routinely seen as one of the award’s weakest winners, which suggests that his reputation has been substantially affected in the meanwhile.

Limited Growth

Critical reputations can be born over years of hard work or after just one amazing film. David Gordon Green got his reputation off the back of George Washington, while Ron Howard has been a consistent workman who has gradually begrudgingly been given respect by critics. Once a success, it can be hard to maintain it. However, it’s even harder to grow and add something new to cinema, as with Anthony Minghella and David O. Russell.

Neither of these directors is particularly poorly regarded; Russell has many detractors due to his on-set altercations and difficult behaviour. Still, people generally accept the quality of films like Three Kings and The Fighter. Yet his reputation has fallen substantially in the past decade. Now, as we covered in the last article, it is true that personal controversies can affect your critical reputation, but simply shrugging and suggesting that this is the only reason for Russell’s critical shift is an easy answer. What might be true in place is that because he emerged with such a distinctive voice, there is a general sense of let-down from critics that he never developed as a major director. His works like Silver Linings Playbook or American Hustle were widely praised upon release, but on reflection, you realise Russell adds little to these genres; no fresh perspectives are brought or new insights.

It feels somewhat unfair to say the same for Anthony Minghella, considering he passed over a decade ago. His best works, like The Talented Mr Ripley and The English Patient, were praised as masterpieces, but upon further appraisal, we realise that these films didn’t particularly add much to their genres; they were rehashing of what had come before. Minghella’s great strength was his lush visuals, but this stylistic approach was fairly predictable and groundbreaking; he wasn’t a particularly versatile or innovative artist. Thus, as the years passed, Minghella’s stock fell.

Lows Make The Highs Seem Low

Russell’s last film Amsterdam was so bad that I wouldn’t be surprised if people started retroactively disliking his previous efforts – which seems to affect directors’ reputations. For example, James L. Brooks, the director of Broadcast News, Terms of Endearment and As Good As It Gets – all films considered brilliant, each receiving their fair share of Oscar nominations.

Brooks’ work is generally beloved for his ability to balance humour and drama and offer insights into his character’s relationships. No one is out here doubting his best works’ quality, yet, the praise for these films has been noticeably less vocal since he has made films like Spanglish or How Do You Know, which failed to receive a similar reception and lacked the sharpness and depth of his prior works. Brooks is still generally considered an elder statesman of the industry but isn’t as well acclaimed as many of his contemporaries.

Martin Brest managed to walk the fine line between commerciality and artistry in the 1980s and 90s with films like Beverly Hills Cop, Midnight Run, and Scent of a Woman; his ability to merge comedy and drama and his knack for guiding great performances led to him being considered one of the steadiest finest directors of the day. But all it took was one film to cause his whole career to collapse; Gigli is widely considered one of the worst films ever made. Since its release Brest hasn’t released another film, leading to a decline in his critical standing. His career can serve as a cautionary tale that one major failure can overshadow a whole host of successes.

You’ll notice neither Brooks nor Brest lacks their supporters, and both are generally well-regarded; this seems to be the case for directors whose worst films overshadow their best; it isn’t that people renounce their earlier works. It’s just that they stop being as vocal. For some directors with cult followings, this might not cause permanent damage, but for some without those followings, like Tom Hooper or Tomas Alfredson, it could.

Tom Hooper won acclaim for theatrical movies like The King’s Speech and Les Miserables, which won praise for their dramatic camera angles, distinctive visual style and careful handling. Hooper even won the Best Director Oscar for The King’s Speech. However, his film Cats was received about as poorly as possible and in the past four years, Hooper’s career has been frozen while critics take potshots at him and dragged his reputation into the mud, suggesting that his visual style distracts from his films’ lack of emotional depth or strong narrative.

Tomas Alfredson emerged as a promising Swedish talent with Let The Right One In, which was praised for its unique take on the vampire genre; he followed it up by becoming one of the few major modern European directors to successfully transition to English-language films with Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy. At the turn of the 2010s, Alfredson was one of the most notable directors in the world. A decade later, we find Alfredson’s reputation considerably smaller; The Snowman was critically panned, and Alfredson has yet to recover from this stumble. Perhaps Alfredson’s struggles highlight the difficulty of transitioning into Hollywood filmmaking and the risk a director takes in attempting the transition.

End of Part II

A director’s job can be thankless; the directors we’ve talked about above have all made incredible movies, from Kevin Smith’s Clerks to Tomas Alfredson’s Let The Right Ones In, and yet their fate is ultimately dictated by a wish-washy concept like ‘critical opinion’ which changes for a multitude of reasons seemingly at whims.

There are yet more directors whose positions in the canon are worth considering. In fact, I have 4 in mind who are all perhaps the most interesting case studies for this phenomenon, although none particularly fit neatly into a category. I’ll create the final part of this research shortly.

One response to “Underrated Directors Whose Critical Reputation Has Fallen”

[…] Part Two: Underrated Directors Whose Critical Reputation Has Fallen […]

LikeLike