With One from the Heart, Francis Ford Coppola bled for his art, throwing his heart, soul and creative maverick spirit into the mix to attempt to create something which would redefine cinema and break it out of its formulaic axis.

In spite of Coppola’s great dreams and intentions, One from the Heart disappeared into the desert with little fanfare. The man many saw as the focal point of New Hollywood had failed; he was bankrupt, and this was a risk Coppola never truly recovered from. In the post-New Hollywood world, Coppola flitted between films, something creating an extraordinary work and other times leaving behind something that the most wretched animal would refuse to take credit for – Jack.

In this period of creative no-mans-land, the maestro turned to a book released by a teenager, S.E. Hinton, Rumble Fish. This work marked a detour from Coppola’s usual grand narratives, away from the Corleone family saga or the phantasmagoric descent into madness that was Apocalypse Now.

Drawing from Hinton’s universe, this monochrome tale offered a dreamlike exploration of youth, time, and self-destructive cycles—undercurrents that echo throughout Coppola’s body of work.

On its release, the movie’s innovative narrative scope and intense visual language didn’t resonate with audiences, its reception a stark contrast to the acclaim that had followed Coppola’s earlier projects. However, like a fine vintage from Coppola’s own vineyard, Rumble Fish ripened over the years. While it may not universally be deemed a classic, it has found its niche among cinephiles.

Upon its release, the film struggled with a challenging dichotomy. It bore the burden of living up to Coppola’s illustrious status while confounding audiences with its stark deviation from his recognisable aesthetic. Critics and audiences, puzzled by Rumble Fish’s monochrome imagery and layered, poetic narrative, struggled to reconcile this new voice with the director they knew.

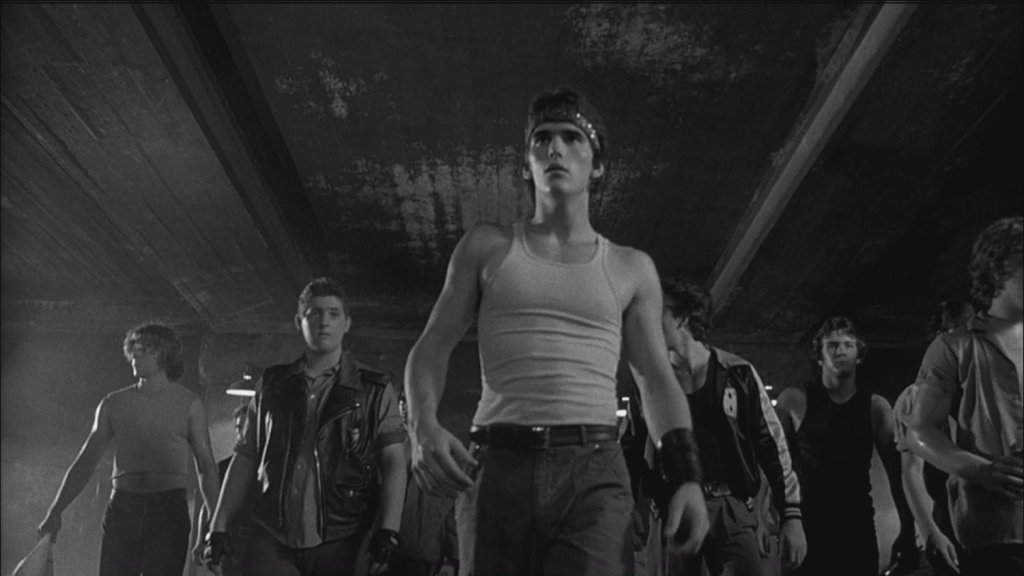

Mickey Rourke & Matt Dillon

Rumble Fish’s pulsating heart lies in the hands of Mickey Rourke, whose portrayal of the mythic Motorcycle Boy adds a potent dose of melancholic gravitas. Rourke unravels the complexities of his character with a subdued intensity, painting the Motorcycle Boy as a paradox—a weary veteran of street battles, yet a poet lost in a place he can barely comprehend.

In the role of Rusty James, Matt Dillon delivers a raw, frenetic performance that complements Rourke’s subdued energy. His frenzied quest for identity and his yearning for the past capture the existential angst of S. E. Hinton’s narrative. Rusty James embodies the doomed aspiration of youth in a world that offers little more than empty promises.

Supporting Rourke and Dillon are the likes of Diane Lane, as the enigmatic Patty, who brings an understated yet compelling presence to the film, and the young Nicolas Cage in the role of Smokey.

Monochromatic Urban Decay

In the aftermath of the polychromatic One From The Heart, Coppola turned towards a more archaic visual aesthetic. Rumble Fish’s striking use of black-and-white cinematography defied the norms of the 1980s and was instead reminiscent of the Expressionist cinema of the 1920s. In doing so, Coppola sets the movie apart from the cinematic landscape of the early 80s and the rest of his filmography. This audacious choice imbues the film with a timeless feel, an evocative portrayal of a world frozen in limbo between the past and the future.

Coppola and his cinematographer, Stephen H. Burum, harness this monochromatic scheme to create a dreamlike, almost hallucinatory atmosphere that permeates the film. The high-contrast imagery, reminiscent of German Expressionism and film noir, is not merely a stylistic quirk—it is a narrative tool used effectively to capture and reflect the inner turmoil of the characters, their existential despair and their struggle against the passage of time. The shadows that play across the faces of Rourke, Dillon, and the rest of the ensemble add a layer of emotional depth and psychological complexity to their performances.

One can’t discuss the visual style of Rumble Fish without mentioning its innovative use of time-lapse photography. Clocks are a recurring motif in the film, their hands spinning at an unnerving pace. They are a haunting echo of the film’s central themes—the transience of youth, the inexorable pull of time, and the corrosive effects of nostalgia. Throughout the film, ticking clocks serve as a spectral soundtrack to the characters’ lives, their constant, unyielding rhythm acting as a stark reminder of an inescapable truth—the ceaseless march of life.

The film’s Expressionistic style extends to its mise-en-scène. The urban deterioration that forms the backdrop to the lives of Rusty James and his cohorts is more than just a setting—it is a character in its own right, a physical manifestation of the societal decay and the spiritual malaise that afflict the film’s protagonists.

The city depicted in Rumble Fish is not a space of opportunity and possibility but rather one of restriction and decline. Rusty James and his companions navigate a world defined by decrepit buildings, vacant lots, and deserted streets—a far cry from the glamorous images of metropolitan living prevalent in popular culture. This sense of degradation mirrors the characters’ own disillusionment, their struggles with their environment, and their individual battles against the limitations imposed upon them.

Furthermore, it heightens the protagonists’ feelings of alienation. In all its decayed glory, the city becomes an echo chamber for the angst and ennui that grip them.

For Rusty James and his gang, the city becomes an arena for their misguided quests for glory and identity. For the Motorcycle Boy, it’s a labyrinthine prison that he can only escape by breaching its literal and metaphorical boundaries—his tragic end on the city outskirts is a testament to the unforgiving nature of this environment.

The environment reinforcing thematic undercurrents is a regular feature of Coppola’s use of location, reminiscent of the war-torn landscapes of Apocalypse Now and the claustrophobic, shadow-drenched interiors of The Godfather—settings that, much like the urban landscape of Rumble Fish, bear witness to their characters’ battles against forces larger than themselves.

The metropolitan dilapidation is a canvas for Coppola to paint a portrait of a world marked by despair and disillusionment, in which his characters find themselves perpetually struggling—against their circumstances, time, and internal demons. It’s a setting that resonates with the bleak reality of many deteriorating city spaces, grounding the film’s expressionistic style in a haunting and familiar reality.

Motorcycles in Rumble Fish

In Rumble Fish, the motorcycle, especially when associated with the Motorcycle Boy, becomes a potent symbol, embodying freedom, rebellion, and a yearning for escape. A metallic steed that promises liberation from the stifling confines they live in.

The Motorcycle Boy is a mythic figure in the film’s universe. His bike becomes an alluring extension of his persona, a tangible manifestation of his defiance against societal norms and relentless pursuit of autonomy. As he rides through the desolate cityscape, he’s not merely a character on a bike but a symbol.

But, the motorbike is not just the embodiment of escape and rebellion—it is also a harbinger of danger and a reminder of transience. This duality is embodied in Motorcycle Boy. Despite his rebellious persona, he is tragically aware of his own mortality and the ephemeral nature of the freedom the motorcycle promises. His ultimate fate underlines the idea that pursuing absolute freedom can have dire consequences.

This use of the bike as a symbol has cinematic precedents. Consider the iconic imagery of Easy Rider, where the motorbikes ridden by Peter Fonda and Dennis Hopper become symbols of a countercultural quest for freedom in the American landscape. Similarly, in The Wild One, Marlon Brando’s motorcycle serves as an extension of his rebellious persona.

Accompanying the roar of the bike is a soundtrack courtesy of Stewart Copeland, best known as the drummer for The Police, who creates a score as unconventional and audacious as the film itself, one that defied typical Hollywood scoring norms of the period.

Copeland’s approach is avant-garde, utilising various traditional instruments and innovative use of found sounds. Ambient noises of the city, including the ticking of clocks, the clang of metal, and the hum of traffic, were woven into the score, grounding the film’s dreamlike narrative in a way that is both familiar and disquieting.

This hauntingly atmospheric soundscape is the perfect auditory mirror to the film’s expressionistic visuals. The dissonant chords, offbeat rhythms, and eerie echoes contribute to a sonic landscape that lifts the film’s dreamlike quality.

Motorcycle Boy and Rusty James

The beating heart of Rumble Fish is the complex relationship between the Motorcycle Boy and his younger brother, Rusty James.

Rusty James lives in the shadow of his older brother’s legend, his every action motivated by a desperate desire to emulate the Motorcycle Boy’s mythical status. Yet, this aspiration is tinged with misunderstanding. Rusty sees only the allure of his brother’s rebel persona, oblivious to the inherent dangers and the existential ennui that it masks. He yearns for the freedom symbolised by the motorbike and the fame his brother commands, unaware that these very things contribute to the Motorcycle Boy’s eventual downfall.

The Motorcycle Boy, on the other hand, represents the disillusioned idealist. He sees the world in stark black and white, the only colour being the eponymous ‘rumble fish’ that he perceives in a pet shop. His struggles with his past, his reputation, and the colourless world around him speak to a profound sense of alienation. His inability to save Rusty from walking the same path is a source of guilt, further complicating their relationship.

Coppola’s use of black and white cinematography captures the contrasts between the brothers, while the ticking clocks underscore the urgency of their predicament. Stewart Copeland’s ethereal score further amplifies their emotional dissonance, lending an almost operatic quality to their interactions.

Coppola was no novice at deftly handling sibling dynamics – look at the Corleone brothers in The Godfather – so it’s not a surprise that he captures this fraternity with a raw honesty that renders it both poignant and heartbreaking.

Rumble Fish

Rumble Fish is the odd-man-out in terms of Coppola’s cinematic progeny; it doesn’t offer the sweeping, operatic narratives that Coppola was known for. Instead, it presented an intimate, disconcerting exploration of urban decay, sibling rivalry, and existential angst. Perhaps unsurprisingly, audiences were left perplexed by this sudden change from the director, although they equally didn’t take to his larger The Cotton Club.

Yet, as the years have rolled by, it has slowly begun to become celebrated. Those who dared to look beyond its unusual style and abstract narrative discovered a film of startling depth and remarkable creativity. They found a film that, despite its initial reception, stood as a testament to Coppola’s genius.

Of course, there are plenty of his films that have seen reappraisal, from One from the Heart to The Conversation. Time has forgiven his sins and praised his indulgences. Films that confound, challenge and grab our scalp and force us to watch should be celebrated. Whether for their ability to provoke, inspire or innovate. Certainly, Rumble Fish doesn’t belong on the same pedestal as The Godfather or Apocalypse Now, but can’t we buy a shorter pedestal so it can have a place too?

One response to “Rumble Fish (1983) – Francis Ford Coppola’s Underappreciated Masterpiece?”

[…] Rumble Fish, Coppola’s second adaptation of an S.E. Hinton novel in 1983, is a stylistically bold and atmospheric film. The story revolves around Rusty James, a young gang leader struggling to live up to his older brother’s reputation in a bleak, urban setting. The film marks Coppola’s continued exploration of youth culture and the struggle for identity. […]

LikeLike