Ken Russell‘s 1971 opus, The Devils, stands as an iconic testament to the filmmaker’s penchant for challenging historical and religious narratives, often confronting them head-on. Set in Loudun, France, during the politically tumultuous 17th century, the film meticulously portrays a time and place ravaged by physical and ideological conflict. Drawing inspiration from Aldous Huxley’s historical novel The Devils of Loudun, Russell delves deep into the historical milieu, constructing an unsettling tableau of the era’s religious and political climate.

Historical Setting

At its core, The Devils tells a story of power, capturing the shifting dynamics between the Catholic Church and the French monarchy under Louis XIII. Russell, consistent with his filmography, explores the complex interplay of faith, authority, and human desire. This thematic landscape is a common terrain in Russell’s films, notably in Tommy and Mahler, where he examines power and faith in different contexts. However, The Devils presents an even more stark and unyielding vision of this power struggle.

Russell presents Loudun as a microcosm of 17th-century France’s larger socio-political environment. The historical setting is integral to the narrative, shaping the characters’ actions and motives. The townspeople, the Church, and the aristocracy are caught up in a swirling maelstrom of hysteria and paranoia, reminiscent of the climate depicted in Arthur Miller’s The Crucible, which also explores religious fanaticism and mob mentality.

The Devils showcases the infamous case of Urbain Grandier, a Catholic priest accused of witchcraft. Russell portrays Grandier in a deeply nuanced manner, humanising a man maligned by history and myth. Throughout his career, Russell often portrayed characters grappling with their spiritual beliefs and worldly desires, a theme evident in his portrayals of composers in The Music Lovers and Lisztomania. Similarly, in The Devils, Grandier’s struggles with faith and personal desires echo the conflicts experienced by the town of Loudun itself, trapped between the Church and the monarchy.

One of the film’s most impactful scenes is the “exorcism” sequence, a riotous and chaotic spectacle that highlights the pervasive fear and hysteria gripping Loudun. This particular scene showcases Russell’s innovative use of visual metaphors and theatrical staging, invoking a sense of the grotesque and absurd, reminiscent of Buñuel‘s The Exterminating Angel and Fellini‘s Satyricon.

In addition to its attention to detail, The Devils stands out for its unflinching portrayal of the era’s brutality. Russell does not shy away from representing the violence and torment of the period, a thematic thread also present in his adaptations of D.H. Lawrence’s works, such as Women in Love and The Rainbow. In this context, The Devils becomes a striking commentary on the horrors that arise from the misuse of power in a deeply stratified society.

Russell’s unique blend of historical detail, thematic depth, and cinematic innovation creates a challenging and unforgettable experience. The film is a testament to Russell’s enduring legacy as a filmmaker unafraid to push the boundaries of storytelling and cinematic form, shedding light on dark chapters of human history while simultaneously forcing us to confront our contemporary demons.

By immersing the narrative in the inescapable power struggle between the Church and the monarchy, Russell daringly explores the malleability of truth and the terrifying implications of unchecked zealotry. Russell provokes thought; he challenges conventional narrative structures, akin to Stanley Kubrick‘s approach in A Clockwork Orange or Martin Scorsese‘s in The Last Temptation of Christ.

The historical setting also allows Russell to highlight the deep-seated misogyny prevalent in 17th-century society, evident in the treatment of Sister Jeanne, a nun in the film. Her plight and persecution echo similar depictions of women in Russell’s works, such as Savage Messiah and Valentino, where female characters often find themselves at the mercy of societal norms.

Furthermore, the setting of The Devils becomes a visual metaphor for the film’s themes, with Russell’s signature use of colour and surreal imagery emphasising the nightmarish quality of this period in history. This innovative approach to filmmaking is reminiscent of the works of his contemporaries, such as Federico Fellini‘s 8 1/2 or Nicolas Roeg‘s Don’t Look Now, all of whom use film as a canvas to explore psychological and social themes.

The Devils embody Ken Russell’s fearless and unique filmmaking style. His innovative use of visual and narrative techniques, combined with a starkly realistic portrayal of the era, results in a film that is not just a historical drama but also a powerful commentary on humanity’s susceptibility to power and fear.

The Ursuline Nuns

Central to the narrative arc of The Devils is the extraordinary case of the Ursuline nuns, who, falling into convulsions and sexual frenzy, seem to be possessed by demonic forces. This unsettling spectacle is one of the film’s most potent symbolic devices, encapsulating Russell’s commentary on the dangerous intersections of power, faith, and sexuality.

The nuns, including Sister Jeanne, who harbours a potent, obsessive infatuation with Father Urbain Grandier, become unwitting pawns in the political machinations of Loudun. Their ‘possession’ triggers a witch-hunt, an alarmingly familiar spectacle, echoing historical events like the Salem Witch Trials. Father Grandier, a symbol of secular power and the object of Sister Jeanne’s desire and the Church’s ire, is squarely in the crosshairs.

Russell’s depiction of the possessed nuns is the film’s disturbing visual and thematic centrepiece. Their convulsions, uninhibited expressions of sexuality, and extreme behaviour are both a manifestation of the psychological pressure exerted by their repressive environment and a potent symbol of the hysteria and fear that grips Loudun. The nuns’ erratic behaviour echoes the sexual and religious tensions found in other films exploring possession and repression, such as William Friedkin‘s The Exorcist and Michael Powell’s Black Narcissus.

The nuns’ possession in The Devils also works as a critique of the use of religion as a tool of power. It underscores how institutional powers can exploit fear and superstition for their own purposes, a theme Russell explores further in films like Altered States and Gothic.

The portrayal of the possessed nuns challenges conventional depictions of women, particularly nuns, in the cinema of the time. They are neither passive victims nor angelic figures but complex individuals driven by suppressed desires and controlled by external forces. Russell further explores this aspect of female psychology in his films Women in Love and The Boy Friend.

The narrative of the possessed Ursuline nuns in The Devils provides a stark and shocking exploration of the manipulation of power and faith. It stands as a symbol of societal hysteria, a weapon of political machinations, and a testament to Russell’s ability to challenge, confront, and provoke.

Oliver Reed’s Father Urbain Grandier

Father Urbain Grandier, embodied by Oliver Reed with a commanding gravitas, stands at the epicentre of the tempest that is The Devils. A figure of charisma and controversy, Grandier is a complex and deeply human protagonist around whom swirl the powerful forces of politics, religion, and suppressed desire.

Grandier’s character can be seen as a paradox. He is both a priest devoted to his flock and a man who indulges in earthly pleasures, pushing against the constraints of his religious vows. This duality is deftly portrayed by Reed, whose brooding, magnetic presence underscores Grandier’s appeal and complexity. Reed’s portrayal of Grandier finds echoes in his other collaborations with Russell, notably his performances in Women in Love and Tommy, where he also navigates characters caught between their desires and societal norms.

In The Devils, Grandier becomes the target of the Inquisition and political enemies, revealing the precariousness of his position and the ruthless machinations of those in power. Yet it is Grandier’s relationship with the repressed nun Sister Jeanne, whose unrequited love spirals into obsession, that truly catalyses his tragic downfall. This narrative thread, charged with emotional intensity and unfulfilled desire, shares common ground with Reed’s performances in films like The Curse of the Werewolf and Paranoiac, which also delve into the darker corners of human psychology.

Russell masterfully weaves together these narrative strands, crafting in Grandier a character who is at once sympathetic and flawed. This is most poignant in the trial and execution scenes where Grandier, stripped of his power and dignity, reveals deep spiritual strength and resilience. The themes of unjust persecution and questioning faith in these scenes find parallels in films like Dreyer‘s The Passion of Joan of Arc and Scorsese‘s Silence.

Father Grandier, as brought to life by Reed, is more than a priest or a victim of political machinations; he is a mirror reflecting the complexities and contradictions of the society in which he lives. His character explores the constant struggle between faith and desire, power and vulnerability, and conviction and doubt. In crafting the character of Father Grandier, Russell and Reed create a figure as compelling as he is tragic, highlighting the enduring power of individual resilience in the face of systemic corruption and manipulation.

Religious and Political Corruption

In The Devils, Ken Russell presents an incisive critique of religious and political corruption, dissecting the insidious abuse of power and manipulation that permeates both the Catholic Church and the French political system of the 17th century. This thematic exploration serves as the fulcrum upon which the film’s narrative pivots, imbuing the historical tale with chilling resonance.

Russell depicts the Church not as a sanctuary of faith but as a hotbed of hypocrisy and power manipulation. The clergy, led by characters such as Father Barre, exploit the people’s fear and blind faith to further their agenda, using the spectacle of possession and exorcism to validate their authority. This exploration of religious corruption mirrors themes seen in works such as Bunuel‘s Simon of the Desert and Scorsese‘s The Last Temptation of Christ, where organised religion is also presented as a tool of control and manipulation.

Similarly, Russell’s portrayal of the French political system is steeped in critique. The monarchy, represented by Louis XIII, is depicted as frivolous and detached, more interested in ostentatious displays of power than the welfare of its subjects. This theme resonates with Stanley Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon, where the ruling classes are also depicted as indifferent to the struggles of the common people.

Perhaps most importantly, Russell explores the intersection of these institutions, demonstrating their complicity in the persecution of innocent individuals. The film lays bare that the Church and the monarchy were not separate entities operating independently but were intertwined systems of power supporting each other. The prosecution and eventual execution of Grandier underscore this point, with both the Church and the state uniting to eliminate a common threat to their power.

The power dynamics in The Devils are reminiscent of the political and religious landscapes in films like Carl Theodor Dreyer‘s Day of Wrath and Michael Reeves’ Witchfinder General, both of which also expose the corruption inherent in systems of power and the tragic consequences for those who stand against them.

The Devils is thus a scathing commentary on the pernicious cycle of corruption, revealing the lengths those in power will go to maintain control. In his characteristic style, Russell does not shy away from controversy, instead confronting viewers with the stark reality of corruption within these revered institutions. The result is a potent exploration of the abuse of power, manipulation, and hypocrisy that continues to resonate with contemporary audiences, underscoring Russell’s status as a filmmaker unafraid to challenge societal norms and expectations.

Sexuality and Repression

A key theme running through the heart of Ken Russell’s The Devils is sexuality and repression, embodied primarily through the character of Sister Jeanne, played with a haunting intensity by Vanessa Redgrave. Sister Jeanne’s passionate infatuation with Father Grandier and her ensuing sexual fantasies vividly illustrate the tensions between desire and chastity, particularly within the confines of the Church.

Russell, in a bold critique of the oppressive nature of religious institutions, presents Sister Jeanne as a woman of depth, caught in a struggle between her sexual desires and the expectations of her religious vows. Her repressed sexuality bubbles to the surface in the form of disturbing fantasies about Grandier, exacerbated by the confines of her cloistered life. This intricate exploration of repressed sexuality is akin to the psychological turmoil experienced by characters in films like Ingmar Bergman‘s Through a Glass Darkly and Jack Clayton’s The Innocents.

In exploring Sister Jeanne’s psyche, Russell unearths the hypocrisy of a Church that condemns natural sexual desire while exploiting it for political gain. The scenes of mass hysteria among the nuns, ignited by Sister Jeanne’s fantasies, highlight the dangerous consequences of suppressing natural human desires. This critique is mirrored in films like Luis Buñuel‘s Viridiana and Michael Powell‘s Black Narcissus, which also delve into sexual repression within religious institutions.

By depicting Sister Jeanne’s sexual fantasies, Russell pushes the boundaries of what was conventionally accepted in cinema. His unflinching exploration of the intertwining of sexuality and spirituality adds an extra layer of controversy to a film already steeped in it. In this aspect, there are parallels to be drawn with the works of filmmakers like Pier Paolo Pasolini, particularly in his film Theorem.

Russell’s depiction of sexuality and repression in The Devils thus serves not only as a character study of Sister Jeanne but also as a broader critique of society and the Church. By illuminating these taboo subjects, Russell challenges the viewer to question their own perceptions and attitudes, reinforcing the film’s enduring relevance and power as a work of thought-provoking cinema.

Style & Beauty

The exploration of sexuality and repression in The Devils, as vividly personified by Sister Jeanne, is complemented and amplified by Ken Russell’s extravagant and provocative stylistic choices. This aspect of The Devils – its daring visual imagery – is integral to the film’s impact, rendering the narrative even more potent and visceral.

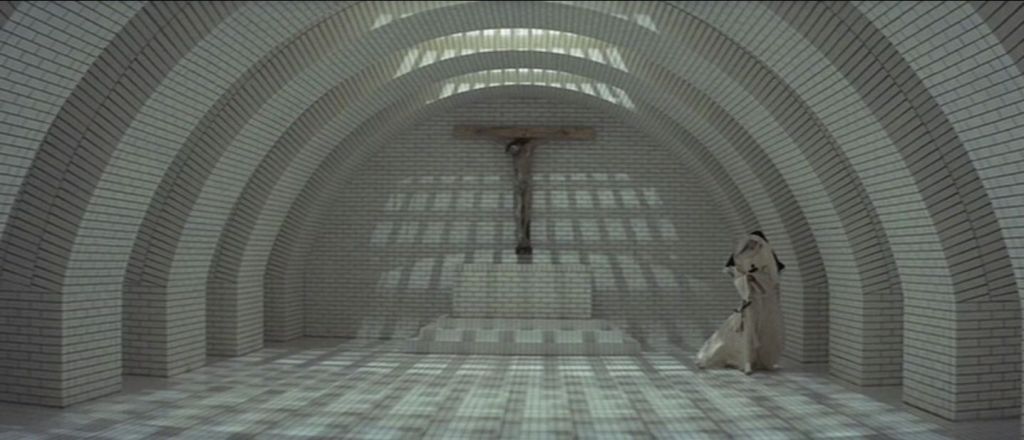

Russell’s visionary direction is characterised by its audacity and creativity, pushing the boundaries of cinematic language. He employs a palette of stark, high-contrast visuals that accentuate the tumultuous atmosphere of the film. The oppressive, monochromatic walls of the nunnery starkly juxtapose with the riotous scenes of possession, while the austere town of Loudun contrasts sharply with the opulent court of Louis XIII. This visual style, heavily influenced by the German Expressionism seen in films like Robert Wiene’s The Cabinet of Dr Caligari, heightens the film’s unsettling and disorientating tone.

The film’s striking costumes, designed by Derek Jarman, also play a crucial role in the storytelling. The severe, restrictive clothing of the nuns, the flamboyant attire of the King, and the sober garb of Grandier – all these serve not just to situate us in the era but also to externalise the characters’ internal states, enhancing the film’s exploration of power, sexuality, and repression.

The theatrical set designs, also by Jarman, are another key component of Russell’s aesthetic vision. The sets, particularly the starkly modernist, fortress-like nunnery, evoke a sense of claustrophobia and confinement, reinforcing the themes of repression and control. These designs recall the imaginative spaces in Federico Fellini‘s 8 1/2 and Jean Cocteau‘s Beauty and the Beast.

The scenes of religious ecstasy and hysteria, so central to the film, are depicted through intense, surreal visuals that leave a lasting impression. In these moments, Russell’s direction takes on an almost hallucinatory quality, pulling the viewer into the chaotic, fevered mindscape of the characters. This approach can be compared to the dream-like sequences in Ingmar Bergman‘s Persona or the hallucinatory scenes in Stanley Kubrick‘s 2001: A Space Odyssey.

The stylistic and visual imagery in The Devils serves not merely as a backdrop but as an active participant in the narrative. Through his audacious visual choices, Russell conjures a cinematic experience that is as aesthetically striking as it is thematically complex, seamlessly marrying form and content in a manner that continues to inspire filmmakers today.

Controversy and Censorship

From its release, The Devils found itself at the epicentre of significant controversy and stringent censorship due to its unflinching exploration of taboo themes. The explicit and provocative content of the film – particularly its portrayal of sexuality, religious iconography, and violence – shocked audiences and authorities alike, leading to bans in several countries and extensive edits in others. Yet, this same audacity has cemented its status as a cult classic and a highly sought-after film for cinephiles.

Critics, censors, and viewers grappled with the film’s depiction of explicit sexual content within a religious setting, a jarring juxtaposition that unsettled many. Scenes like the infamous ‘Rape of Christ’, where possessed nuns desecrate a statue of Jesus, were particularly controversial; some saw them as an unnecessary and offensive provocation. However, this critique can be questioned when considering the broader context of Russell’s work. These scenes are not designed for shock value alone but as potent symbols of institutional corruption and the weaponisation of religion.

Physical and psychological violence also played a significant role in the film’s controversy. The brutal execution of Grandier, depicted in harrowing detail, was deemed too graphic by some critics. This criticism, while valid in acknowledging the visceral intensity of the scene, overlooks the fact that the violence is not gratuitous. Instead, it serves as a chilling indictment of the inhumanity of religious and political persecution, a critique aligned with contemporary films like Arthur Penn‘s Bonnie and Clyde or Sam Peckinpah‘s Straw Dogs.

The film’s stylistic boldness was another point of contention. The modernist sets, the high-contrast cinematography, the dissonant score, and the surreal visual sequences drew mixed responses. Critics who were less receptive to Russell’s artistic vision labelled the film as overly theatrical and accused it of forsaking historical accuracy. However, it can be argued that Russell’s stylised approach was not intended to provide a historically faithful account but rather a highly subjective, metaphorical interpretation of events, much like in Sergei Eisenstein‘s Battleship Potemkin or Federico Fellini‘s Roma.

Despite the controversy and censorship, The Devils is a testament to Ken Russell’s artistic courage. Its explicit content and provocative themes are integral to its exploration of power, corruption, sexuality, and faith, aligning it with controversial yet acclaimed films like Pier Paolo Pasolini‘s Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom or Stanley Kubrick‘s A Clockwork Orange.

In considering the criticisms of The Devils, it’s important to distinguish between discomfort with the film’s content and disagreement with its intent. While the film is undoubtedly challenging and confrontational, these elements are purposeful, meant to provoke reflection and question societal norms. They are not gratuitous attempts at shock but integral facets of a complex, unapologetic exploration of deeply controversial themes. In this light, the film’s controversy and censorship can be seen as a testament to its enduring power to provoke, challenge, and unsettle.

Further Reading

Altered States, Altered Spaces: Architecture, Space and Landscape in the Film and Television of Stanley Kubrick and Ken Russell by Matthew Melia.

The Devils movie review & film summary (1971) | Roger Ebert

Why Ken Russell’s ‘The Devils’ Deserves Divine Resurrection – FilmSchoolRejects