Few filmmakers have left as indelible a mark on the world of cinema as Jean-Luc Godard. From his initial foray into film criticism in the early 1950s, it was clear that Godard was not just a film enthusiast but someone to whom cinema was life.

From 1955 onwards, Godard started channelling his passion for cinema into filmmaking, embarking on a journey that would transform him from an aspiring auteur into one of the pioneers of the French New Wave. This was a period of experimentation and exploration, a time when Godard was finding his unique cinematic voice.

Working with limited budgets and resources, he produced a series of short films, including Une Femme Coquette, Operation Beton, Charlotte et Son Jules, and All the Boys Are Called Patrick. Although not as renowned as his later works, these early shorts serve as a testament to Godard’s innovative vision, each film offering a glimpse into the directorial style that would revolutionize cinema with the release of Breathless in 1960.

By studying these early works, we gain insight into the formative years of cinematic genius. We see a young filmmaker deeply in love with cinema, fearlessly experimenting with narrative, style, and technique and laying the groundwork for a career that would redefine the very notion of what cinema can be.

Narrative Experimentation

When one delves into the early works of Jean-Luc Godard, there’s a clear sense of a fearless artist, already steeped in the art of narrative experimentation before he burst onto the global cinematic stage. This predilection for pushing boundaries set the tone for his subsequent contributions to the French New Wave, but it’s the undercurrent in his early shorts that truly indicate the breadth and audacity of his unique storytelling approach.

In films like Une Femme Coquette and Operation Beton, we see the seeds of the narrative defiance that would become a Godard signature. His stories, far from being presented in an easily digestible linear manner, are complex, multifaceted explorations of character and context. For instance, in Une Femme Coquette, a seemingly simple plot becomes a layered commentary on society and morality through Godard’s innovative narrative structure.

But Godard’s iconoclastic vision was not confined to merely how a story unfolds. Rather, it extended to a comprehensive deconstruction of genre. Known and celebrated for his genre-bending tendencies, Godard blurred the lines between comedy, drama, and romance, disrupting traditional categorizations with his bold and innovative style.

Charlotte et son Jules and All the Boys Are Called Patrick provide fascinating glimpses into Godard’s penchant for genre subversion. Charlotte et son Jules, for instance, presents itself as a dialogue-heavy comedy-drama, but Godard infuses it with philosophical musings and poignant observations, transforming it into a far more profound exploration of human connection.

This blend of comedic, dramatic, and romantic elements is similarly evident in All the Boys Are Called Patrick, where a seemingly straightforward story of mistaken identity is elevated through Godard’s deft handling of dialogue and visual cues, reminiscent of his love for the masters of Hollywood’s Golden Age like Howard Hawks and Alfred Hitchcock.

In these films and others, Godard unveiled a willingness and determination to experiment and defy established genre norms. They serve as testaments to a filmmaker daring to carve a path that was uniquely his own, breaking away from the conventional and, in doing so, reshaping the cinematic landscape.

Early Style

Jean-Luc Godard’s cinematic vision was not only confined to the realm of narrative and genre. In fact, his unique approach to visual storytelling played an equally significant role in cementing his status as a trailblazing filmmaker.

Godard’s early films demonstrate a budding command over the visual language of cinema. For example, All the Boys Are Called Patrick uses dynamic camerawork to accentuate the lightheartedness and confusion of its story, transforming what could be a standard comedy into a memorable exploration of identity and human connection. Much like the others in Godard’s early filmography, this film underscores the power of visual storytelling in the hands of a skilled filmmaker.

The inspiration behind Godard’s innovative visual style can be traced back to the vibrant artistic and cultural climate of the 1950s. As part of the Cahier du Cinema critics alongside luminaries like Francois Truffaut and Eric Rohmer, Godard was deeply immersed in contemporary discourses around the cinema. This immersion, coupled with the influence of radical art movements such as Situationist International, had a profound impact on Godard’s cinematic style. This is evident in his preference for realism and a sense of immediacy, which marked a significant departure from traditional filmmaking.

Political & Social Commentary

Jean-Luc Godard’s early films were not mere cinematic experiences but also cultural critiques that captured the zeitgeist of the era.

The concept of identity, the pursuit of freedom, and the quest for meaning found ample exploration in his short films, provoking viewers to engage with the human condition on a deeper level. In All the Boys Are Called Patrick, mistaken identity becomes a means to explore notions of selfhood and individuality.

Although these early films hint at the overt political posturing Godard would adopt later in his career; they are, nevertheless, a testament to a filmmaker deeply attuned to the socio-political undercurrents of his time.

Influences and Homages

An unabashed cinephile, Godard’s love for cinema is vividly evident in his early works. He masterfully incorporated references and allusions to classic films and filmmakers, engaging in a dialogue with the past while striving to push cinema into the future. A reverence for the likes of Howard Hawks, Alfred Hitchcock, and Jean Renoir permeates his work.

Yet, his filmic references were not mere homages but part of a deeper exploration of cinema and its evolving language. It’s a testament to Godard’s deep knowledge of film history and his fervor for contributing to the evolution of the medium.

Simultaneously, Godard’s films also interacted with the contemporary cultural trends of the 1950s. Whether it’s the distinctive jazz-infused soundtrack of Charlotte et son Jules, or the fashionable aesthetics of Une Femme Coquette, Godard’s works resonated with the spirit of the era, making them not just films but cultural artifacts of their time. His ability to blend homage with contemporary cultural engagement resulted in narratives that were both a reflection of and a commentary on the society from which they emerged.

Experimental Sound

In Jean-Luc Godard’s early films, sound is more than an auditory backdrop. It becomes an integral part of the storytelling process. Godard used voiceover narration and innovative sound design techniques to enrich his narratives and craft an immersive auditory experience for his audience. In films such as Operation Beton and Une Femme Coquette, the soundscapes are as layered and nuanced as the visual frames.

The combination of dialogue, ambient noises, and sound effects forms an unconventional auditory tapestry that reflects the thematic complexity of Godard’s narratives. It’s a practice that Godard would continue to refine in his later works, such as in Pierrot le Fou and Weekend, where sound design plays a pivotal role in conveying the films’ underlying themes and emotions.

Similarly, music was a key element in Godard’s cinematic toolbox. His early films showcased his ability to integrate music as both a narrative device and a reflection of the cultural climate. Carefully selected tracks were woven into the fabric of his films, enhancing the visual storytelling with added emotional depth. The jazz-infused soundtrack of Charlotte et son Jules, for instance, not only sets the film’s mood but also contributes to its overall narrative rhythm.

Naturalistic Performances:

Godard’s early works were marked by an emphasis on naturalism in performance. Far from the over-dramatized acting styles prevalent during the era, Godard encouraged his actors to embrace spontaneity and authenticity. This approach resulted in performances that pulsated with raw realism, making the characters more relatable and the narratives more engaging.

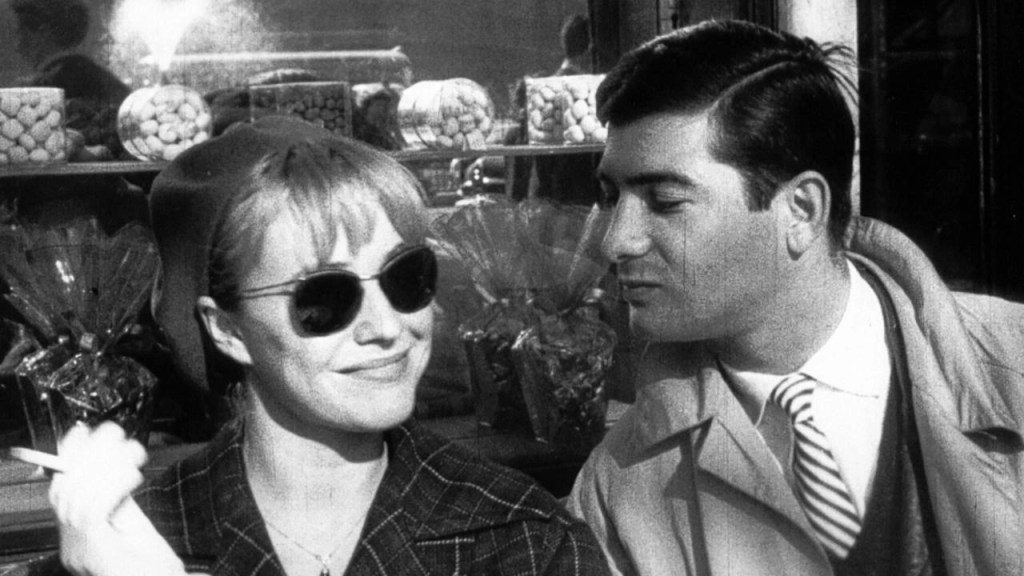

In All the Boys Are Called Patrick and Charlotte et son Jules, the performances of the actors exude a sense of naturalism that aligns perfectly with Godard’s aesthetic. This focus on naturalistic performances becomes a recurring element in Godard’s filmography, especially evident in his later films like Breathless and Vivre Sa Vie, where actors like Jean-Paul Belmondo and Anna Karina deliver performances marked by a compelling mix of spontaneity and authenticity.

Godard’s early shorts, thus, served as the testing grounds for his innovative cinematic techniques and thematic concerns that would continue to evolve and inform his illustrious career in filmmaking.

Resourcefulness and DIY Filmmaking:

The genius of Jean-Luc Godard is perhaps best exemplified in his ability to create within the constraints of limited resources. His early films like Une Femme Coquette and Operation Beton were crafted within shoestring budgets, necessitating ingenuity, and resourcefulness.

Yet, these limitations did not hinder Godard’s creative vision. Instead, they spurred him to devise creative solutions and workarounds, further honing his innovative filmmaking approach. His films did not merely overcome their budgetary constraints; they seemed to thrive on them, with each film boasting a distinctive aesthetic and style reflective of Godard’s creative problem-solving skills.

Take Charlotte et son Jules for instance, a film largely confined to a single location – an apartment. Rather than being a hindrance, the minimal setting offers a concentrated space for Godard’s narrative experimentation and character exploration. Similarly, in Operation Beton, Godard made effective use of the documentary form, a typically budget-friendly genre, to critique industrial labor practices.

These early films showcase Godard’s dexterity and adaptability as a filmmaker and his knack for turning potential setbacks into creative triumphs. Even in the face of budgetary limitations, his commitment to filmmaking remained unwavering, setting the stage for the cinematic revolutions he would soon spearhead.

The First Steps of Jean-Luc Godard’s Camera

While some might overlook Godard’s early shorts as being forgettable or insignificant, dismissing their importance would be a mistake. Each of these films is an early hint of the genius that would later explode onto the world cinema stage.

The same could be said of the humble beginnings of other filmmaking giants, such as Steven Spielberg‘s short film, Amblin’, or Christopher Nolan‘s self-financed debut feature, Following. Godard’s early films, much like these examples, serve as fascinating precursors to the following groundbreaking works, forming the foundation upon which one of cinema’s greatest directors built his illustrious career.