I think everyone whose ever watched a movie in the last 30 years has come to appreciate Quentin Tarantino. Yes, his films can be a bit excessive, but there’s something so great about his movies, whether its the non-linear structure of Pulp Fiction, where Tarantino weaves together stories like an artisan or the witty, gripping and glorious violence of Inglorious Basterds. It’s hard not to love the video store cinema nerd who achieved his dreams and metamorphosised into a marquee director whose every film is eagerly anticipated.

Tarantino’s planned retirement isn’t exactly a hush-hush secret, he’s openly spoken of making just ten movies for a while now, and with his recent turn towards extra-curricular activities, such as books and podcasting, it signals that he’s preparing for life after directing.

The exact logic behind Tarantino’s 10 films is a bit vague, and what he counts as ‘10’ seems to be too, but generally, it sounds like he’s doing it to protect his own legacy, which makes sense considering what a cinephile he is.

Tarantino once referenced Howard Hawks‘ Rio Lobo as an example of a once-great director’s decline, inspiring me to revisit this controversial film and, ultimately, Hawks’ extraordinary career.

Howard Hawks, a filmmaker of exceptional versatility, was lauded for his ability to craft iconic films across multiple genres. From Scarface and His Girl Friday to The Big Sleep and Rio Bravo, Hawks had an enviable repertoire of classics that showcased his gift for narrative, character development, and atmospheric world-building. However, his final film, Rio Lobo, didn’t receive quite the same acclaim. Tarantino’s indictment of it encapsulated the general sentiment of the time. A product of 1970, the movie seemed to embody a disconnect with the new age of cinema emerging in the ’70s.

Rio Lobo is, in essence, a story about honour, camaraderie, and retribution set against the backdrop of the post-Civil War American West. It had all the hallmarks of a classic Hawks Western: the stoic hero, the loyal sidekicks, the scheming villains, and the enthralling landscape. Yet, something seemed amiss.

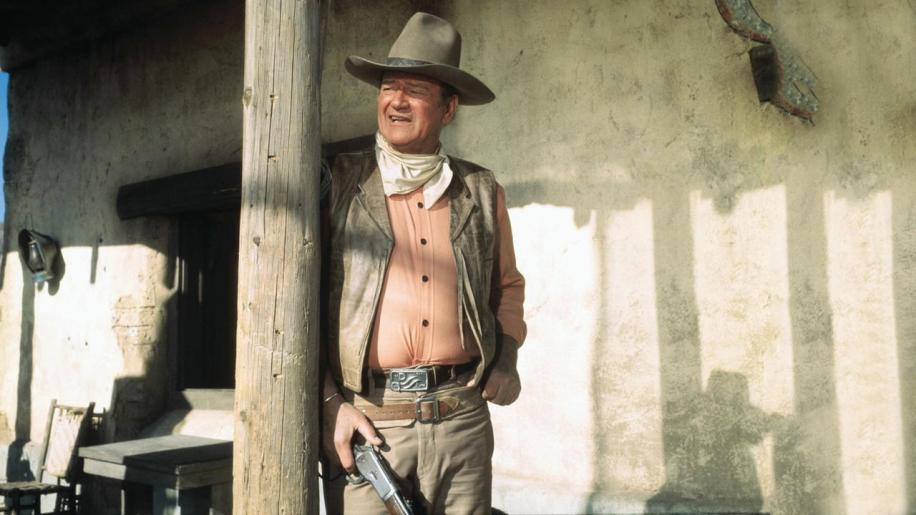

The ever-charismatic John Wayne starred in his fifth film with Hawks, delivering a competent performance as the principled Civil War veteran. The film benefits from a certain comforting familiarity, echoing previous collaborations like Rio Bravo and El Dorado. It has some striking action scenes, a testament to Hawks’ knack for staging dynamic sequences. Jerry Goldsmith’s stirring score adds a layer of depth, while the cinematography beautifully captures the stark grandeur of the Wild West.

However, these strengths can’t mask its shortcomings. Wayne’s performance, while sturdy, lacked novelty. The dialogue doesn’t quite deliver Hawks’ usual sharp wit, often lapsing into predictability. And the film, in its pursuit of comfort and familiarity, ends up feeling derivative. This was a lesser echo of previous Hawks-Wayne collaborations, not a fresh, revitalising take. The supporting cast, barring Jack Elam, leave much to be desired, none of them standing out for any good reasons. The ending lacks the dramatic payoff you’d expect from a Western showdown, and the pacing is inconsistent. There is a noticeable absence of the intricate character development that had been a hallmark of Hawks’ earlier work.

Tarantino was not wrong in his criticisms. Rio Lobo was certainly not Hawks at his best. But to dismiss it entirely may be an oversight. The film still showcased elements of Hawks’ filmmaking genius, even if they were less consistent than in his earlier work.

Reflecting on Hawks’ career, Rio Lobo seems to be an underwhelming finale. It lacked the innovation and originality of his groundbreaking works like Bringing Up Baby or Gentlemen Prefer Blondes. Yet, every director has their highs and lows, and as an ardent Hawks fan, I can’t help but appreciate even the lesser lights in his oeuvre.

Could Hawks’ legacy have been stronger without Rio Lobo? Perhaps. But then, isn’t the risk of failure an inherent part of creative expression? Tarantino may have the luxury of an early retirement, but not all directors share that privilege or desire. Tarantino can use his name power to host a podcast or write books, but there are at most ten directors with that ability. Then there’s the fact that Hawks was known for his ceaseless dedication to his craft. For him, filmmaking was not just a job but a passion.

Rio Lobo, in my assessment, isn’t a bad film; in fact, it’s a decent film. One of Wayne’s better 1970s efforts and certainly not as bad as some of Hawks’ contemporaries’ latter efforts. It is by no means Hawks’ strongest film, but nor it is his worst. I’d argue that Red Line 7000, A Song Is Born, and Tiger Shark are much worse films.

Rio Lobo’s familiarity might be its undoing; ultimately, its predictability makes it easier to directly compare to his far superior films like Red River or Rio Bravo. Perhaps if Hawks had gone a different route less associated with old Hollywood, say a crime film, he’d have gotten more acclaim. It feels like he slept-walked through the film and directed-by-numbers.

Rio Lobo offers an interesting look at a great director’s career twilight and serves as a reminder that even legends have their off days. What’s your take on the last films of great directors? Do you agree with Tarantino’s fear of overstaying one’s welcome? Or do you find a certain charm in the last hurrahs of cinema’s legends? Let’s start the conversation.