Earth (#292)

1930, Aleksandr Dovzhenko, 1:24, USSR, Drama

Dovzhenko was a poet of nature, a radical mystic more akin to Blake than Marx, and in this film this love is dramatized in images of tremendous power.

J.N. Thomas

L’Age d’Or (#455)

1930, Luis Bunuel, 1:00, France, Surrealism

Nonsensical, erotic, scandalous, revolutionary: Luis Buuel’s surrealist masterpiece L’ge D’Or is not for those of a nervous disposition.

Jamie Russell

People On Sunday (#455)

1930, Robert Siodmak & Edgar G. Ulmer, 1:14, Germany, Slice of Life

The mark of a professional is reliability; the talented amateur delivers wonders as happy accidents but lacks the technique to be malleable or, for that matter, predictable. An amateur is a force of nature, which is why a satisfying performance by an amateur is overwhelming and awe-inspiring, as seen in the 1930 silent film “People on Sunday”.

Richard Brody

City Lights (#40)

1931, Charlie Chaplin, 1:23, USA, Slapstick Romance

The sublime City Lights was Chaplin’s riskiest and most complicated undertaking, a silent film made just as studios were fully committed to sound. Utilising music and sound effects, it was also a marriage of sentiment and slapstick, the elements of which had to mesh with acrobatic precision. Setting the tone is the opening, in which The Tramp endures a series of self-inflicted run-ins with a gigantic civic monument, a scene that is at once side-splittingly funny, risqué, and beautiful.

Molly Haskell

M (#47)

1931, Fritz Lang, 1:57, Germany, Thriller

A classic tale of catechizing human virtue in pre-Nazi Germany, Lang’s first talkie keeps us terrorized with onscreen dialogue and asynchronous off-screen sounds. The adumbral opening is flawless Expressionism—menacing cuckoos, leering abandonment and the awakening of sheer terror within one silhouette.

Samantha Vacca

Limite (#271)

1931, Mario Peixoto, 2:00, Brazil, Drama

Sometimes cited as the greatest of all Brazilian films, this silent experimental feature (1931) by poet and novelist Mario Peixoto, who never completed another film, was seen by Orson Welles and won the admiration of everyone from Sergei Eisenstein to Walter Salles… The remarkably luscious and mobile cinematography (for which cameraman Edgar Brazil had to build special equipment) alone makes it well worth seeing.

Jonathan Rosenbaum

Tabu: A Story Of The South Seas (#292)

1931, F.W. Murnau, 1:24, USA, Romance

The recycling of narrative tropes common to both Murnau and his co-writer, Robert J. Flaherty, blunts whatever claim the film might have to anthropology, but the feature is most fascinating as a showcase for a master challenging himself. The reliance on natural light forces Murnau, one of the great wielders of shadow, to deal with intense sunlight and shifting light positions, and compositions regularly display a conflict between keen framing and the predictability of the objects being framed.

Jake Cole

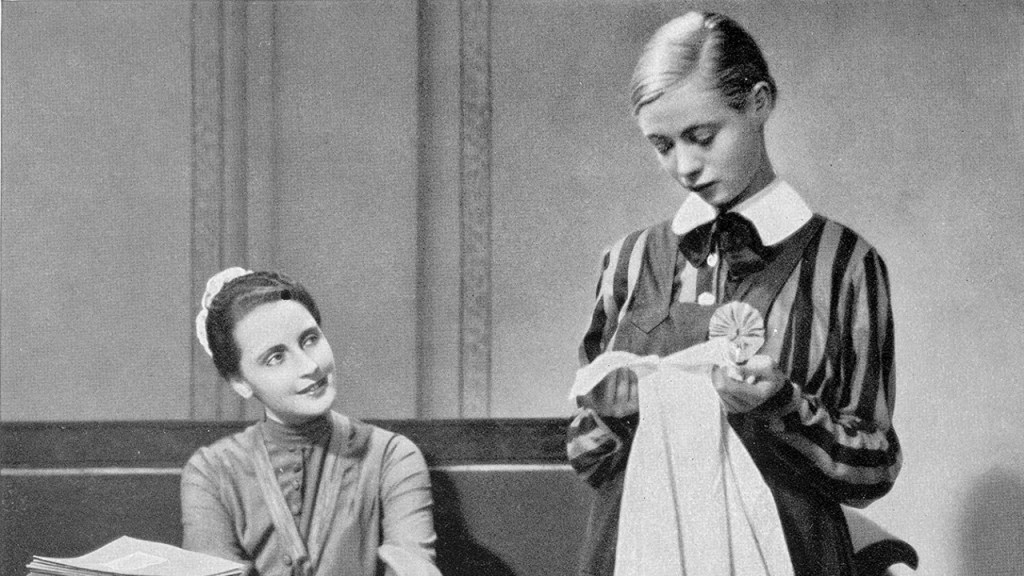

Mädchen In Uniform (#407)

1931, Leontine Sagan, 1:28, Germany, Drama

No outline of the story could attempt to convey a sense of the adroitness with which the producers have caught the schoolgirl spirit that bubbles even under such repressive conditions, the naturalness of manner revealed by the youthful players.

Len G. Shaw

Vampyr (#165)

1932, Carl Th. Dreyer, 1:13, Germany, Horror

Dreyer takes one crucial scene—in which the female victim of a vampire half transforms and is almost overcome with bloodlust but unable to go through with biting the hero. It is Dreyer, however, who highlights the erotic as well as the terrifying aspect of this scene—thus founding an entire subgenre of vampire movie, in which the kiss of the vampire is a tantalizing promise as much as a disease-ridden threat.

Kim Newman

Trouble In Paradise (#175)

1932, Ernst Lubitsch, 1:23, USA, Romantic Comedy

There is order and morality in Lubitsch’s immorality, as in the 1932 Trouble in Paradise, one of his finest achievements. . . . The movie achieves the rare feat of making both women seem entirely worthy of the hero’s affections.

Farran Smith Nehme

Duck Soup (#227)

1933, Leo McCarey, 1:08, USA, Slapstick

Arguably the funniest movie ever made. The brothers claim that the film’s story—about a leader (Groucho) who arbitrarily takes his country to war—was never intended as satire, but only Dr. Strangelove matches its audacity in sending up the follies of nationalism and conflict.

Scott Tobias

Zero For Conduct (#271)

1933, Jean Vigo, 0:44, France, Coming-of-Age

It is hard for me to imagine how anyone with a curious eye and intelligence can fail to be excited by it, for it is one of the most visually eloquent and adventurous movies I have seen.

James Agee

King Kong (#338)

1933, Merian C. Cooper & Ernest B. Schoedsack, 1:44, USA, Monster Movie

That’s the kind of fever dream this picture works on one’s brain – through its dreamy matte paintings, foreground miniatures, rear screen and stop motion animation – we accept its logic entirely, ferocious pterodactyls and all – and we mourn this primal, compound force of innocence and righteous fury. He’s either like Lenny in Of Mice of Men who can’t help but accidentally pet those rabbits to death (did John Steinbeck watch Kong?), or, if he could talk, he’s akin to The Tempest’s Caliban.

Kim Morgan

L’Atalante (#37)

1934, Jean Vigo, 1:28, France, Romance

It’s no exaggeration to call “L’Atalante” one of the greatest films in the history of cinema… An ecstatic film that, at the same time, captures the physical and emotional burden of physical labor, the roaring clamor that goes into the industrial landscape, and the grandiose yet exquisite new forms that result.

Richard Brody

It Happened One Night (#407)

1934, Frank Capra, 1:45, USA, Romantic Comedy

The Depression may be softened by moonlight and shining eyes, but it is everywhere visible in It Happened One Night, from the woman on the bus who faints from hunger to the freight car full of hoboes who wave back at a joyous Pete as he races to propose to Ellie. One of the loveliest shots in the movie is the exquisite track that follows Ellie as she makes her way to the autocamp’s communal shower, while children chase each other and weary adults prepare to get back on the road.

Farian Smith Nehme

By The Bluest Of Seas (#271)

1936, Boris Barnet, 1:11, USSR, Romantic Comedy

It’s difficult to account for what makes this movie so exquisite, apart from the characters and their quirks (such as one man’s ticklishness) and the beauty of the idyllic setting. [Film historian Bernard] Eisenschitz seems to be on the right track when he says that the film is unclassifiable, that it’s “certainly not a comedy even if it provokes laughter.

Jonathan Rosenbaum

Modern Times (#72)

1936, Charlie Chaplin, 1:27, USA, Slapstick

There are many sequences which will become famous. The philosophy is evident. It is clear that Chaplin’s answer to modern times is that if the individual does not conform he is taken away in a van to prison or to hospital.

Robert Herring

A Day In The Country (#156)

1936, Jean Renoir, 0:40, France, Slice of Life

The charm of the film seems almost too easily won, but Renoir’s real brilliance emerges in the way the light tone is subtly modulated into the profound sadness and regret of the conclusion.

Dave Kehr

La Grande Illusion (#150)

1937, Jean Renoir, 1:53, France, Prison Film

This elegy for the death of the old European aristocracy is one of the true masterpieces of the screen.

Pauline Kael

The Awful Truth (#407)

1937, Leo McCarey, 1:32, USA, Screwball Comedy

Of all the great movies, this may be the one that most resists description in words – although some of film culture’s finest writers, including James Harvey and Stanley Cavell, have tried their best. . . . Above all, the film is a monument to the sheer, magical lovability of its stars.

Adrian Martin

Bringing Up Baby (#127)

1938, Howard Hawks, 1:42, USA, Screwball Comedy

Possessed by an overwhelming sense of comic energy, Howard Hawks’ screwball masterpiece heaps on misunderstandings, misadventures, perfectly timed jokes, and patter to the point that it’s easy to overlook how rich and fluid it is a piece of filmmaking, effortlessly transitioning from one thing into the next.

Ignatiy Vishnevetsky

The Rules Of The Game (#15)

1939, Jean Renoir, 1:46, France, Drama

Jean Renoir’s The Rules of the Game has been part of the film canon for so long that it’s valuable to remind audiences how gloriously alive and just plain fun it is. Low comedy walks hand and hand with tragedy and beauty throughout; the film is frothy one minute, nearly apocalyptic the next, and so you’re never fully allowed to gather your bearings.

Chuck Bowen

The Wizard Of Oz (#120)

1939, Victor Fleming, 1:42, USA, Musical

A work of almost staggering iconographic, mythological, creative and simple emotional meaning, at least for American audiences, this is one vintage film that fully lives up to its classic status.

Todd McCarthy

Only Angels Have Wings (#140)

1939, Howard Hawks, 2:01, USA, Drama

Only Angels Have Wings is one of the standouts of [Hawks’] impressive career, but also one of his most sobering films. With a frank attitude towards death and a romantic yet melancholy view of life on the edge, it’s an existentially tough work of blunt philosophy.

Adam Cook

The Story Of Last Chrysanthemums (#292)

1939, Kenji Mizoguchi, 2:22, Japan, Romance Drama

The Story of the Last Chrysanthemum becomes an authentic dual tragedy. The movie has the shape of a Camille-like tearjerker, but it’s dramatically rigorous and tough-minded. Emotionally, it packs a one-two punch.

Michael Sragrow

Young Mr. Lincoln (#455)

1939, John Ford, 1:40, USA, Biopic

An ingeniously tight-focused yet historically resonant view of the future President’s rise to prominence… Perhaps no filmmaker bore the burden of historical consciousness as deeply, as seriously, and as humanly as Ford did; his “friendship” with Lincoln had a firm artistic basis.

Richard Brody

Gone With The Wind (#455)

1939, Victor Fleming, 3:44, USA, Epic Period Drama

Even though the habits of movie- goers have changed over the years, it’s easy to see why this film provoked such an outpouring of praise and adulation during its initial release, and why its stature has grown with the passage of decades.

James Berardinelli