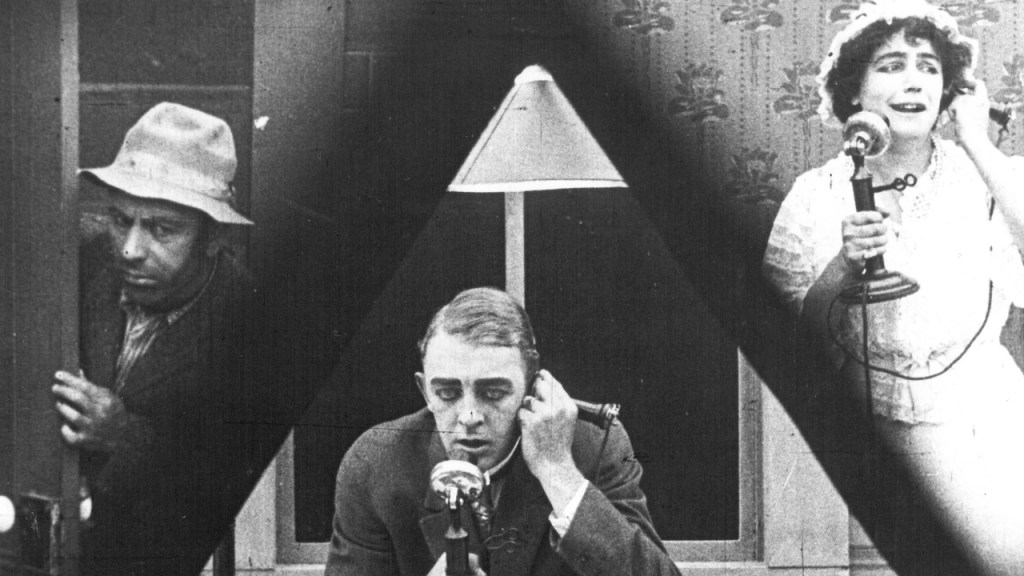

Suspense (#455)

1913, Lois Weber & Phillips Smalley, 0:10, USA, Thriller

Suspense is an oft-cited entry in Weber’s filmography, primarily due to its historically significant use of split screen, but it is an often overlooked — if not outright ignored — important early film in horror history. And its central tale of a woman who hears a man break into her house while her husband is working late is compelling on its own.

Alexandra Heller-Nicholas

Intolerance: Love’s Struggle Throughout The Ages (#251)

1916, D.W. Griffith, 3:17, USA, Epic Anthology

Intolerance, conceived on an even grander scale than The Birth of a Nation, was immediately recognised as a powerful humane statement and a towering work of art. However, the way the movie covered more than 2,000 years of history in its four interwoven stories of prejudice and oppression puzzled audiences and proved a box-office disaster, from which Griffith never fully recovered.

Philip French

The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (#407)

1920, Robert Wiene, 1:11, Germany, Psychological Horror

The first thing everyone notices and best remembers about “The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari” (1920) is the film’s bizarre look. The actors inhabit a jagged landscape of sharp angles and tilted walls and windows, staircases climbing crazy diagonals, trees with spiky leaves, grass that looks like knives. These radical distortions immediately set the film apart from all earlier ones, which were based on the camera’s innate tendency to record reality.

Roger Ebert

The Kid (#455)

1921, Charlie Chaplin, 1:08, USA, Melodrama

The Kid reveals how closely Chaplin’s irreverent slapstick could be intertwined with his sentiment. And rather than simply making the Tramp more palatable to middle-class tastes of the day, Chaplin’s new emotional range provided the core of his lasting appeal.

Tom Gunning

Nosferatu (#210)

1922, F.W. Murnau, 1:34, Germany Gothic Horror

Whereas Stoker’s vampire is killed by a stake, Nosferatu introduced the device of the vampire who is destroyed by the sun’s rays and where Stoker’s vampire casts no shadow, Murnau’s does throughout to great dramatic effect. At the climax of the film, the shadow of the vampire’s hand grasps at Mina’s heart and she arches in pain. Murnau may have broken the laws of vampires, but he has obeyed the laws of the cinema.

Michael Koller

Our Hospitality (#407)

1923, Buster Keaton & John G. Blystone, 1:13, USA, Slapstick

Buster Keaton’s ingenuity, acrobatics, and romanticism flourish equally in this antic twist on melodrama, from 1923, which he co-directed with John G. Blystone. It’s set mainly in 1830 and is loosely based on the historical Hatfield-McCoy feud. The directorial artistry features riotous disguises and sly stagecraft, and the climactic chase, with its gallant heroics, leads to a waterfall, where Keaton performs one of the most terrifying, precisely timed stunts ever filmed.

Richard Brody

Greed (#210)

1924, Erich von Stroheim, 2:20, USA, Psychological Drama

Part of the story’s greatness in both the novel and Stroheim’s adaptation is the degree to which it makes the deterioration of all three characters terrifying real and believable. And some of the worst damage done by MGM’s reduction was to make this process seem forced and abrupt rather than a logical development of these working-class characters, all of whom are treated as sympathetic as well as horrifying at separate junctures in the story.

Jonathan Rosenbaum

Sherlock, Jr. (#66)

1924, Buster Keaton, 0:45, USA, Slapstick

This 1924 comedy finds Buster Keaton anticipating most of the American avant-garde of the 70s: he plays a projectionist who falls asleep during the showing of a detective thriller and projects himself into the action. Keaton’s appreciation of the formal paradoxes of the medium is astounding; his observations on the relationship between film and the subconscious are groundbreaking and profound. And it’s a laugh riot, too.

Dave Kehr

The Last Laugh (#292)

1924, F.W. Murnau, 1:41, Germany, Psychological Drama

Should the porter suddenly lose this uniform and the nebulous prestige it affords, what would become of him, not to mention that society in which so much can rest on so unstable a thing as pride? This seems to be the question at the sad yet sour heart of Der letzte Mann (The Last Laugh, F.W. Murnau, 1924), a film suffused with game-changing innovations and mixed sympathies.

Tope Ogundare

Battleship Potemkin (#61)

1925, Sergei Eisenstein, 1:15, USSR, Soviet Montage

Because Battleship Potemkin is an appeal to fellow-feeling and collective action, it is only right that the restoration work creates a more immersive film, one that places no barriers between a 21st-century audience and its monumentally powerful imagery.

Pamela Hutchinson

The Gold Rush (#313)

1925, Charlie Chaplin, 1:36, USA, Slapstick

Although the opening extreme long shots of an endless line of prospectors struggling up over a mountain pass are impressive, much of the action takes place in studio sets, sometimes standing in for alpine locations. Both the cabins, Black Larsen’s and Hank Curtis’, are like little proscenium stages, with the action captured from the front. Yet the film depends on its brilliant succession of gags and on the Prospector’s status as the underdog who is also the resilient and eternal optimist.

Kristen Thompson

The General (#111)

1926, Buster Keaton, 1:18, USA, Slapstick

With his athleticism, precision and comic timing, Keaton more or less invented the action movie [with The General] and, despite its modest running time, this has an epic ambition… It is as if Keaton is in the very forefront of movie-making possibility.

Peter Bradshaw

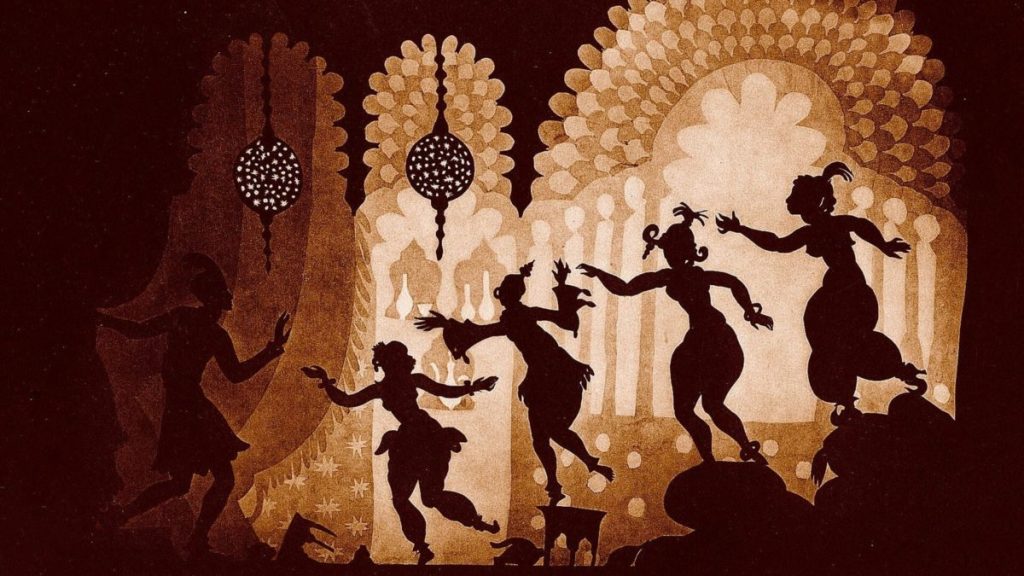

The Adventures Of Prince Achmed (#338)

1926, Lotte Reiniger, 1:06, Germany, Animated

There’s no denying that this art form [silhouettes], originating as far back as the 1st millennium BC with traditional shadow puppetry, is as complex in the way it’s created and the reactions it can evoke as it is simple in how it might appear to the casual observer… THE ADVENTURES OF PRINCE ACHMED is not just a prime example of the art form, but it also has the distinction of being the oldest surviving feature-length animation, a consequence worthy of Reiniger’s achievement.

Kathleen Sachs

A Page Of Madness(#407)

1926, Teinosuke Kinugasa, 1:11, Japan Psychological Drama

…A madhouse riot of a movie. Traumatic and nauseating, it’s easily the most horrifying movie made during the Silent Era, a weird and queasy dance of death directed by former female impersonator/future Oscar and Palme d’Or winner Teinosuke Kinugasa and written by future Nobel laureate Yasunari Kawabata.

Ignatiy Vishnevetsky

Sunrise: A Song Of Two Humans (#11)

1927, F.W. Murnau, 1:35, USA, Romance

It’s the dictionary definition of a classic film. It won the first ever Academy Award, has been placed on the National Registry, and was the first silent film put out on Blu-Ray. It routinely places in “Best Of” lists, it’s a picture whose artistry is intended to be accessible to mass audiences. It is conventionally beautiful, conventionally narrative, conventionally stirring. It needs no apologies or excuses, it’s just excellent in every way. But did you know it was a comedy?

David Kalat

The Passion of Joan of Arc (#24)

1927, Carl Th. Dreyer, 1:22, France, Religious Drama

It’s a harrowing film, claustrophobic in its use of close-ups that unblinkingly record Joan’s emotional and mental state. Each frame becomes a canvas for Dreyer’s unflinching portrait of suffering.

Jamie Russell

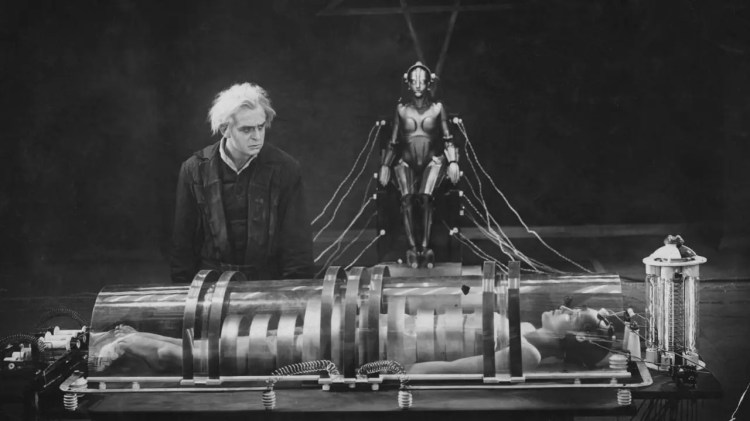

Metropolis (#89)

1927, Fritz Lang, 2:30, Germany, Sci-Fi

Lang’s aerial views of choreographed crowds are positively Riefenstahlian; his sky-scraping, heavens-reaching city looks glorious as ever. Metropolis marshals all the resources of the German film industry to warn against the persuasive streamlining of mass production and new media; it must, paradoxically, be seen to be believed.

Mark Asch

Napoleon (#237)

1927, Abel Gance, 5:30, France, Epic Biopic

As a sensory experience, there is simply no equal to Abel Gance’s Napoléon. The intensity of its images and their rhythms take the breath away and exhilarate the body, touching places and hungers that are hard to name.

Ginger Varney

The Crowd (#292)

1928, King Vidor, 1:44, USA, Melodrama

The film is moving without being unequivocally happy or tragic, the theme summed up by one of the film’s intertitles: “the crowd laughs with you always… but will cry with you for only a day”.

Bruce Hodson

Un Chien Andalou (#152)

1929, Luis Bunuel, 0:16, France, Surrealism

This is the avant-garde masterpiece with the razor across an eyeball and dead donkeys sprawled across pianos.

Caryn James

Pandora’s Box (#292)

1929, G.W. Pabst, 2:11, Germany, Crime

Louise Brooks’s famous bobbed hairstyle precipitated her eternal inimitability… Pabst understood this, which is why when Brooks’s doomed flapper from Pandora’s Box flees a courtroom after a murder conviction, she cuts her hair to become almost unidentifiable—to be like other women, except perhaps for the curly-blond gal pal who longs for her affections… It’s an act of desperate self-preservation in a film wickedly chockablock with exciting displays of amorous exaltation and domination.

Ed Gonzalez

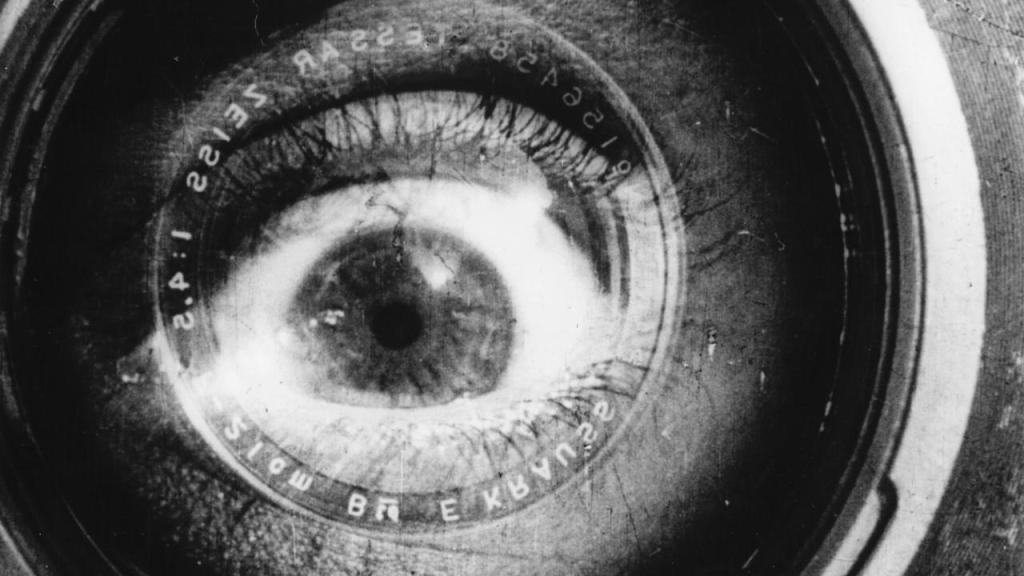

The Man With A Movie Camera (#10)

1929, Dziga Vertov, 1:08, USSR, City Symphony

The sheer jouissance of Vertov’s experimentation in a film defined by odd angles, jump cuts, split screens, tracking shots, double exposure and… playful montage, might alone propel Man with a Movie Camera onto greatest film ever lists.

Tara Brady